Between them, the BBC,

EMI, and TDK are making a wealth of

fascinating visual material available

to us which allows those who are interested,

to understand better, how the great

conductors achieved the results they

did. Long may this continue, as it is

a marvellous way to be entertained by

the really great musicians of the past,

and in some cases even the present.

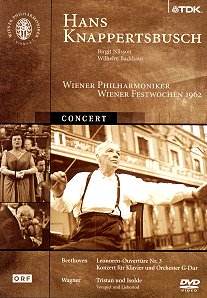

This DVD, if issued

in today’s environment, would be classed

as a "celebrity event" and

indeed that is just what it is, except

that these terms were not around when

the recordings were made. The undoubted

star of the concert is the conductor

Hans Knappertsbusch. I will not be tempted

into the pretentious epithet "Kna"

as some reviewers use, so here Knappertsbusch

will be Knappertsbusch.

Knappertsbusch had

the reputation of being very light on

rehearsals, indeed when first encountering

the Vienna Philharmonic in 1929, he

rehearsed only the first half of the

concert. About the second half, Beethoven’s

Eroica symphony he told the orchestra

"You know the work, I know the

score." A contemporary violinist

in the orchestra remembers "He

radiated such confidence on the evening

of the concert that a rehearsal had

indeed not been necessary." We

are not told in the notes whether the

present concert was rehearsed beforehand,

but there is no cause for worry – the

results are excellent.

Tradition would have

us believe that Knappertsbusch’s interpretations

were highly controversial, which was

part of his legendary reputation, but

here, all is largely quite normal given

the historical basis of the concert.

His beat is the clearest it could be,

and the orchestra, is intent on watching

it intently, something which is often

missing from current day concerts. Maybe

he was tempered by his soloists, particularly

the 78 year old Wilhelm Backhaus who

had said when interviewed "Believe

me, not a day of my life has gone by

without my trying to play the introductory

bars of this concerto. That is so terribly

difficult and I have never really been

satisfied."

Based upon current

evidence, this goes very well, as far

as the rest of the concerto is concerned,

apart from a few finger problems which

will not bother all but the most fussy

listeners / watchers of this DVD. The

picture is in grainy black and white,

and the sound whilst being in mono,

is quite clear without being in the

least bit "hi-fi". There is

a little distortion but this is in no

way serious, and the overall experience

is very entertaining as well as being

a fascinating historical document. I

never realised that history could be

so interesting.

The concert starts

with a funereal paced account of the

Leonore No. 3 Overture, which soon picks

up speed and ends with a large rush

of adrenaline to produce a very good

atmosphere for the concerto. The film

during the interval between the two

works concentrates on the latecomers

finding their seats, which I find adds

a little humour to the proceedings.

This livens up the monochrome film,

and I am sure that this part was severely

edited, as no stage hands could re-arrange

the orchestra and bring on the piano

in such a relatively short space of

time.

Backhaus sits at the

piano like a god playing like a dream

with absolutely no show of emotion other

than what is emanating from his fingers.

There are some rhythmic distortions

but it is the skill of the conductor

accompanying his soloist perfectly around

each such minor change of tempo within

the bar lines which makes this performance

so interesting.

After the concerto,

the orchestra is joined by the then

young Birgit Nilsson singing the glorious

Liebestod from Wagner’s Tristan und

Isolde. Caught in her absolute prime,

this most illuminating of Wagnerian

sopranos gives a superb rendition of

this most moving Wagner "bleeding

chunk," and it rounds off a most

satisfying programme.

John Phillips