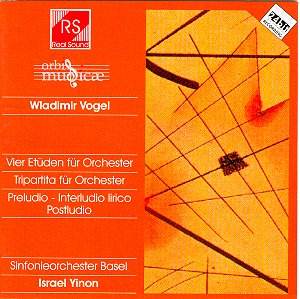

Things (musical and

other) are never what you think they

are or might be. When I received this

disc, I thought that someone had – at

long last – decided to consider Vogel’s

music worth recording. However, browsing

through several websites, I realised

that a number of his works are actually

available on discs, although these may

have passed unnoticed at the time of

their release. I recently

reviewed a new Guild release (GMCD

7250) including his Flute Concertino;

but I was not aware of the existence

of a recording of one of his early groundbreaking

works (Wagadu’s Untergang durch

die Eitelkeit, composed in 1930,

available on MGB CD-6128, which I have

not heard, or his Violin Concerto

of 1940, available on MGB CD-6169, which

I have also not heard) whereas several

shorter works have also been recorded

by DIVOX (though this one is presently

out of print) and GALLO. Nevertheless,

the present release featuring three

large-scale, substantial orchestral

works fills quite a gap in Vogel’s discography

and provides for a most welcome re-assessment

of his output.

Vogel was born in Moscow

to a German father and a Russian mother.

When he was 15, he met Skryabin who

was to prove a lasting influence on

his music. The outbreak of World War

I put an end to his musical studies.

His family was interned for being reichsdeutsch

and was later exiled in a village near

the Urals. He was nevertheless able

to continue his studies. After the end

of the war, Vogel and his family were

allowed to emigrate to Berlin where

he resumed his musical studies with

Heinz Tiessen who was quite helpful

in providing the budding composer with

a thorough aesthetic background but

who proved disappointing as far as composition

was concerned. Vogel wanted to study

either with Schönberg or with Busoni,

and eventually studied with Busoni.

Some early works, including a string

quartet which was lost during World

War II, attracted some attention; but

it was Scherchen’s first performance

of Zwei Etüden für Orchester

that was decisive in putting Vogel’s

name firmly on the musical map of his

time. In 1933, however, he left Germany

for France and Belgium before settling

in Switzerland where he stayed for the

rest of his life. He was given Swiss

citizenship in 1954.

The Vier Etüden

für Orchester is one of

his first substantial orchestral works.

The first two etudes Ritmica Funebre

and Ritmica scherzosa, composed

in 1930, were first performed by Scherchen

and soon taken up by other conductors

such as Stokowski and Ansermet. They

drew much favourable critical appraisal,

even from the terrible Swiss critic

Aloys Mooser. They were recorded in

the early 1930s but the Nazi authorities

had these recordings destroyed. In 1932,

he added two further etudes: Ostinato

perpetuo and Ritmica ostinata.

(Note the importance of the words Ritmico/ritmica

and Ostinato/ostinata which clearly

reflect some of Vogel’s formal preoccupations

at that time.) Ritmica funebre

is a powerfully impressive processional

opening with heavy pounding drums, moving

headlong with considerable energy, often

bringing Honegger to mind. True to its

title, Ritmica scherzosa is a

nimble Scherzo of some orchestral virtuosity,

in which Vogel uses the hocket technique

exhilarating effect. Mirroring the first

etude, ostinato perpetuo is another

long slow movement of gripping power

and intensity in which thematic material

from the first etude is briefly restated,

as in the magical coda. The final etude

Ritmica ostinata caps the whole

set with another quick, nervous movement

of a somewhat lighter character ending

with a march-like ostinato. This brings

Shostakovich to mind, slowly tapping

away before the final assertive chord.

This is powerful, deeply serious stuff,

displaying – among other things – a

remarkable orchestral flair.

The Tripartita

was completed in 1934 and first performed

at the 1936 Venice Triennale. It marks

a considerable advance on the earlier

Etüden, both in formal

thinking and orchestral mastery. As

suggested by the title, the piece is

in three panels of unequal length played

without a break. A long central Adagio

is framed by shorter, brilliant outer

sections of some energy, sometimes verging

on violence. The emotional weight of

the piece rests in the powerfully expressive

Adagio. This mighty work, too, drew

favourable comment from Mooser who nevertheless

wrote that "il ne faut chercher

ni subtilité de la pensée,

ni raffinement de la matière

sonore, encore moins nuances du sentiment",

which is – to say the least – somewhat

exaggerated. You just have to listen

to the beautiful central section which

has some marvellous orchestral touches

belying Mooser’s harsh words (I often

wondered what it was like when he did

not like a piece).

Some time later, in

about 1937, Vogel turned to twelve-tone

music without ever adhering to it unconditionally.

His use of dodecaphony, informing much

of his later music, was never dogmatic

and quite comparable to Frank Martin’s

own attitude towards the scheme, albeit

with different results.

Preludio – Interludio

lirico – Postludio was composed

in 1954 on the occasion of the thirtieth

anniversary of Busoni’s death. In the

Prelude, Vogel uses a seven-note theme

from Busoni’s Toccata

for piano. To this he adds five further

notes, producing a basic twelve-tone

row that he later uses with considerable

freedom, i.e. from Schönberg’s

point of view. The long Interlude

also uses the twelve-tone row as a theme.

The Prelude and Postlude

are somewhat simpler in structures,

the Postlude relying again on

hocket. Preludio – Interludio

lirico – Postludio is undoubtedly

a major work from Vogel’s mature years.

It displays to the full some remarkable

though hard-won mastery and formal freedom.

I cannot but express

the highest praise for this enterprising

release which, I hope, will put Vogel’s

highly personal music back into the

catalogue. I look forward to having

more of his orchestral music by the

same forces as here. Their committed

playing carries hard-to-resist conviction.

Excellent recording and excellent insert

notes. If a complete recording of Vogel’s

opus magnum Thyl Claes, fils de

Kolldraeger (which plays for

nearly four hours) might still be a

near-impossible task, a recording of

the suites (there exist a suite drawn

from the second part as well as three

shorter orchestral suites made in 1958)

might be a musically satisfying alternative.

Warmly recommended.

Hubert Culot