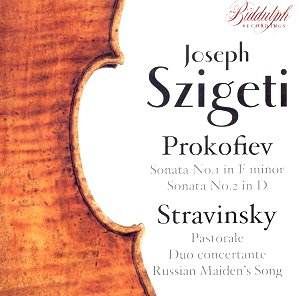

Biddulph is back. After

a period of inactivity, the label that

gave Vengerov his first commercial disc,

that branched out from historic violin

to piano and orchestral recordings,

and that kept violin fanciers ever intrigued,

has now inaugurated its rebirth. Who

else should it turn to but that sinewy

intellect of the string world, Joseph

– or Josef or many years ago Joska –

Szigeti, subject of some of the label’s

first ever releases. In new livery –

suitably violinistic – they concentrate

on Szigeti’s 1945-49 recordings of Russian

literature, ones that have proved in

the past elusive and difficult to track

down.

Szigeti’s recording

of the First Violin Concerto of Prokofiev

with Beecham is a benchmark interpretation

and one of his greatest recordings.

I’m sure that for many it occupies the

same kind of place as Oistrakh’s or

Heifetz’s readings do in the later Concerto.

Less well known perhaps is his championing

of these sonatas. He recorded the first

with Joseph Levine, as here, and then

a decade later with Balsam. Likewise

the Second Sonata was recorded with

the fine pianist Leonard Hambro and

then again in the 1959 sessions with

Balsam. In the First, Szigeti is forwardly

recorded and one can hear that sometimes

rather coarse and brittle tone as he

negotiates Prokofiev’s complex technical

and expressive demands. Someone like

Oistrakh lavished far greater tonal

heft and expressive reserves on this

music but there’s no doubting Szigeti’s

control of architecture or local detail.

His bowing does come under pressure

in the Allegro brusco and at some moments

so does his intonation but he reconciles

the rhetoric here as few do – the tensile

and the lyric – and also the moments

of rusticity and dance embedded in the

score. The troublesome Hubay bowing

does let him down occasionally and there

is, at moments, some distinctly unlovely

playing. His Andante redeems much; well-shaped,

full of momentum and direction, never

sectional, linearity in action, no great

tonal intensity – a profile both reflective

and withdrawn. Szigeti and Levine are

rather quicker than the more avuncular

Oistrakh and Frieda Bauer in the finale

and they cultivate real drive, not troubling

to italicise little lyric details and

the ending is first class.

The Second Sonata is

an Oistrakh-inspired violin version

of the work originally written for flute

and piano. It doesn’t bear quite the

weight of demands of the earlier sonata

and Szigeti, recorded four years earlier,

sounds rather more comfortable. Once

again the original recording level was

skewed in favour of the string player

but Hambro emerges with witty credit

and Szigeti deadpans through the Scherzo,

and is unlingeringly charming in the

Andante.

Coupled with Prokofiev

is Stravinsky. There’s an evocative

Pastorale with some impressive collaborators

and an affecting Russian Maiden’s Song.

The most important of the Stravinsky

items though is the Duo Concertante

and this recording with the composer

as accompanist replaced the Samuel Dushkin-Stravinsky

recording made for Columbia in 1933.

Here one finds Szigeti full equipped

to meet intellectual challenges. He

lavished considerable delicacy and understanding

on the two Epilogues and in the faster

music his wiry, abrasive, resinous tone

– uneasy and unsettling sometimes –

acts as a fine contrastive tool, whether

intended or not. His Gigue is full of

rhythmic control and he lavishes some

very expressive portamenti in the Dithyrambe

where his tone is not too astringent,

even if the lower strings can deaden

rather.

The recordings catch

the presence of the originals well.

Notes are interesting – with quotations

from the violinist and from Roland Gelatt

as well as producer Eric Wen’s own sleeve

notes. If I might make the habitual

trainspotter’s plea I must note that

there are no matrix or issue numbers

given and I hope their omission doesn’t

reflect a new policy. Otherwise, a warm

welcome back to this innovative and

important label and its first new release.

Jonathan Woolf