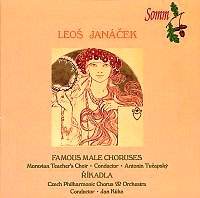

Somm has dug into the

archives to return to the catalogue

a pretty much self-recommending disc,

the bulk of which is sung by the Moravian

Teachers’ Choir in a 1969 traversal

of some of Janáček’s

greatest male choruses. The Moravian

Teachers’ Choir, the international name

for the Choir of the Association of

Moravian Teachers, was founded in 1903

by Ferdinand Vlach and was well known

to Janáček. Tucapsky, known better

now perhaps as a composer of

distinction and a British resident,

conducted them from 1959-69 and this

may well have been his final recording

with the choir he’d conducted for a

decade.

Of the choruses set

some are on folk texts or more purely

romantic ones. The second here, Coz

ta nase briza (Our Birch tree) was

written by the Czech writer and Smetana’s

librettist Eliska Krasnohorska whilst

Klekanica is on a dialect text

– and dedicated to this choir, by the

way. Ceska legie (The Czech Legion)

is a nationalist epic celebrating the

establishment of Czechoslovakia in 1918.

Maybe surprisingly the text of Potulny

silence

(The Wandering Madman) is derived from

Tagore, whom Graham Melville-Mason’s

elucidatory notes remind us, Janáček

had heard in Prague in 1921. Kantor

Halfar is a not so coded political

protest against German authoritarianism,

oppression and the suppression of the

Czech language – and Sedmdesat tisic

still more of a political statement.

Whether epic, romantic, theatrico-dramatic,

dialect or philosophical these settings

make particular and significant demands

on a choir. The demands of characterisation

co-exist with those of technique and

expression. The Choir’s capacities in

these respects are truly remarkable.

The B Flats in the second of the choruses

are perfectly even and sustained and

they negotiate the, at first, simple

but increasingly complex freedoms and

"speech song" setting of Rozlouceni

with staggering finesse and technical

address. The declamatory complexity

and metrical complications of Ceska

legie with its varieties of mood,

tempo and sonority are conveyed with

the highest possible skill. The compass

of the choir is even across the range,

from head voice to the vertiginous Slavic

basses; single voices emerge from the

mass with fervent musicality and there

is a real sense of theatrical, sometimes

almost operatic, engagement with the

source material. Tucapsky encourages

dynamism and lyricism to flourish; his

guidance of the many varied complex

rhythmic effects is a testament both

to his skill and the sophistication

and understanding of the Moravian Teachers’

Choir.

Rikadla, the

nursery rhymes, come from the final

years of Janáček’s

life and were inspired by cartoons in

one of the composer’s favourite newspapers

and one to which he had contributed

his fare share of journalism over the

years. The work thus dates from around

the time of the composition of Mladi

and was originally

written for smaller forces, with Janáček

enlarging the piece later in 1925, after

it was first performed, for Chamber

Choir and ten instruments. These are

deft and amusing little sketches with

characterful contributions from a contingent

of the Czech Philharmonic. The

recording still sounds splendid and

there’s only one cause for complaint;

texts of four of the male choruses have

been omitted to save space. Not a good

idea. Otherwise an unalloyed pleasure.

Jonathan Woolf