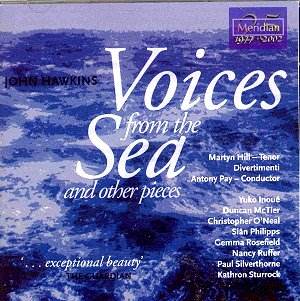

Although the name of

John Hawkins will be new to many he

is a composer with a substantial body

of work to his credit. His 1980 Sea

Symphony, the work on which his

reputation chiefly rests to date, has

been broadcast on more than one occasion.

This Meridian release is the first disc

to be solely devoted to his music and

is therefore particularly welcome, showing

him to be a composer of sound technique

with a clear sense of craftsmanship.

Hawkins’ principal

teachers were Elizabeth Lutyens and

Malcolm Williamson, although it is perhaps

to the latter that his music is closest

stylistically. The language is broadly

rooted in tonality whilst not shying

away from the use of dissonance where

the dramatic context of the music dictates.

In Voices from the Sea, the song

cycle that Hawkins wrote immediately

following his Sea Symphony, there

is also a feeling of the presence of

Britten at times, notably in the string

writing and the dramatic sweep of the

melodic lines, but the music is no less

effective for it and Hawkins shows that

he is able to create a sense of atmosphere

that is very much his own.

The six poems used

were selected by the composer from submissions

to the annual poetry competition of

The Seafarers Education Service, each

reflecting differing aspects of life

at sea and being wide ranging in their

dramatic breadth and subject. Scored

for tenor and strings, this live recording

is of the first performance in April

1985 and Martyn Hill is on fine form,

giving strong, colourful and vivid accounts

of all six songs.

The eight remaining

works are all for more modest chamber

forces and range from the solo oboe

in Disturbed Nights, to various

combinations of strings and piano. Indeed,

a glance through Hawkins list of compositions

reveals that works for strings form

an important thread through his output.

This is no doubt partly due to his close

collaboration with violist Paul Silverthorne

and double bassist Duncan McTier. McTier

has probably done more for the solo

double bass repertoire than any other

player and Worlds Apart, commissioned

by him in 1996, is an inventive, virtuoso

showpiece that exploits the many differing

facets of a much underestimated solo

instrument. Here Hawkins succeeds not

only in displaying the technical possibilities

of the instrument but also in creating

a compelling sense of musical drama.

McTier figures again in Waiting:

Tango, this time in duet with Paul

Silverthorne whose largely lyrical viola

line is beautifully played in an enigmatic

miniature that once again places the

double bass in an unfamiliar yet effective

role as musical protagonist.

Of the other works

for strings, Gestures, for two

violas, is a dramatic, virtuosic duo

of an intensity that defies its relative

brevity. In contrast Quietus,

for string trio, begins elegiacally

but soon develops into a concise, lyrically

charged single movement that provides

further evidence of Hawkins dramatic

gestural abilities. Shadows,

adds piano to viola and double bass

and is a response to a poem by Ursula

Vaughan Williams, proceeding atmospherically

from rippling, mysterious piano figurations

and transforming itself into a central

waltz before returning to the twilit

world of the opening bars. Brief

Encounters is a terser affair, slightly

more astringent in its three fleeting

movements and imaginatively utilising

the textural contrasts of the solo viola

and flute.

The Variations

for piano is the most ambitious of the

works after Voices of the Sea

and also the longest at just under twelve

minutes. The eight highly contrasting

variations on the opening chordal theme

culminate in a passacaglia, with Hawkins

effectively negotiating the various

transitions from the nostalgic to the

occasionally violent through which the

music passes on its journey. Disturbed

Nights for solo oboe, shows a very

different use of variation form, a cumulatively

intense response to an initial lullaby

like theme that takes as its starting

point a parent’s increasing desperation

for its child to sleep. Hawkins here

makes considerable demands on the soloist

and Christopher O’Neal reciprocates

with playing of impressive technique

and lyrical charge.

Hawkins’ music is not

marred by unnecessary flamboyance but

rather distinguished by its innate sincerity.

All of these works, whether small or

large in scale, are emotionally involving

and impressively measured in their expression.

Proof that he is capable of sweeping

gesture on a larger scale is evident

in Voices from the Sea. I have

heard few contemporary song cycles that

capture both beauty and austerity as

vividly.

Christopher Thomas

Hubert Culot

has also listened to this disc

At a little over twenty

minutes, Hawkins’ song cycle Voices

from the Sea is by far the most

substantial work here. In 1980 the Marine

Society commissioned Hawkins’ large-scale

orchestral work Sea Symphony

which drew many favourable comments

at the time of its first performance.

The composer wanted to follow it with

a vocal piece, also inspired by the

sea. The director of the Seafarers Education

Service suggested a recently published

anthology of entries to its annual poetry

competition Voices from the Sea.

The composer selected six poems for

his song cycle. These poems in which

sailors reflect on their feelings when

at sea offered considerable scope for

musical characterisation, always clearly

evoked but never overdone by the composer.

Loneliness at night, longing for home

and the often harsh realities of a sailor’s

life are vividly translated into music,

in turn dreamy, sad, dramatic or bittersweet,

in which the sea – as in Britten’s Peter

Grimes – is always present,

if at times in the background. I was

particularly impressed by the third

movement Crow’s Nest and the

fourth movement Home is the Sailor,

the latter depicting a wreckage but

ending with a deeply moving coda. The

whole cycle is a beautifully varied,

contrasted, and often moving achievement

that does not pale when compared to

Britten’s orchestral song cycles. The

superb string writing often brings Britten

but also Grace Williams to mind, but

none the worse for that. Quite the contrary,

and one cannot but wonder why this magnificent

piece of music is not heard more often.

The sound of the live recording of the

work’s first performance is quite satisfying

indeed, and the performance itself is

excellent.

All the other pieces,

for various instrumental combinations,

are much shorter but never lightweight.

In fact, the Variations

for piano is a minor masterpiece in

its own right and a quite substantial

piece of music that should appeal to

any pianist willing to add an accessible

modern work to his/her repertoire.

There are not that

many substantial works for double bass

and piano, so that Hawkins’s sizeable,

often virtuosic Worlds Apart

is a most welcome, worthwhile addition

to this instrument’s rather scant repertoire.

Disturbed Night

for solo oboe is another set of variations

in all but the name, and yet another

fairly substantial work in much the

same league as Britten’s Metamorphoses

and Francis Routh"s Tragic

Interludes.

Most other pieces are,

as already mentioned, rather shorter.

Some of them are written for unusual

instrumental forces such as the bittersweet

Waiting: Tango (for viola

and double bass), the short suite of

three concise, contrapuntal movements

Brief Encounters (for

flute and viola), the superbly crafted

miniature Shadows (for

viola, double bass and piano) and Gestures

(for two violas) which is a concise

work of some virtuosity. The final item

Quietus for string trio

based on Hawkins’ earlier viola piece

Urizen was written for

a concert in memory of Silverthorne’s

wife Mary. This beautifully moving miniature

provides this varied and appealing selection

of Hawkins’ beautifully crafted music

with a peaceful, moving conclusion.

Hawkins’ sincere, honest

and impeccably written music is clearly

the work of a distinguished musician

who obviously has things to say and

who knows how to say them in accessible,

communicative terms likely to appeal

to larger audiences without ever compromising

or writing down to them. Well worth

looking for.

Hubert Culot

see also

review by Rob Barnett