Some forty years ago - or more - I heard a beautiful

song on the radio, with no idea who it was by, or who was singing.

The latter I still don't know - but some time later, browsing

in a bookshop, I came across some sheets of music, the covers

decorated in a richly romantic vein. And here, to my delight,

was that very song - its title Marienlied, the composer

Joseph Marx.

Determined to investigate the music of this composer

I soon realised that he was almost totally neglected. However

I was lucky enough to find scores of both Violin Sonatas (bravo

Travis & Emery!), the huge Romantisches Klavierkonkonzert,

the Suite for cello and piano and a quantity of equally beautiful

songs and piano pieces. Some time afterwards the pianist/composer

Patrick Piggott sent me a rather scratchy old tape of Marx's Castelli

Romani for piano and orchestra (then in his own repertoire

which included such rarities today as Turina’s Rhapsodia Sinfonica,

Fauré’s Ballade, Bax’s Saga Fragment, the

Hurlstone, Ireland and ApIvor concertos and Field's 4, 5, 6 and

7) and from that date Marx has been a composer whose works I have

valued highly and sought after.

At the time also I was dimly aware of a big orchestral

work which had gone missing - not just neglected but actually

lost - a work described by Marx's biographer Andreas Liess as

"a late romantic symphony of incredibly orgiastic euphony and

voluptuous impressionism" - shades of Bax's Spring Fire!

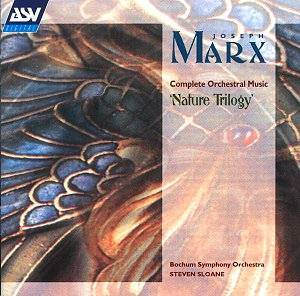

And now here, in this fabulous recording. if

not the missing Herbstsymphonie itself (which might yet

be pursued?) we have a refreshingly tantalising introduction to

the even lesser known orchestral works of Joseph Marx with a promise

from ASV that all the orchestral and chamber music will follow.

Of course the sprawling Piano Concerto - recorded

not so long ago in Hyperion's series of romantic concertos - must

surely have excited many who have not succumbed to the pervasive

disease of minimalism - for this music is the farthest remove

- not only from those desiccated scores, but also from those mean

spirited souls who are distrustful of excess of any kind no matter

how lovely it may be. For surely this music is excess? But if,

in the 20th century, with all the panoply of a range of orchestral

device and colour flooding the canvas in the wake of Debussy,

Strauss and Delius, Marx can revel ecstatically in Nature in an

even more 'unbuttoned' fashion than Beethoven's "happy feelings

on venturing into the countryside" then who should complain? Wasn't

it Fenby who said of Delius something to the effect that there

is: ‘little enough beauty in the world today - why complain of

a surfeit of it in one man?'

The mention of Debussy, Delius and Bax is not

at all inappropriate - for it is a Delian sense of 'flow' that

carries this ecstatic music over a plethora of dominant sevenths,

interrupted cadences and climactic 6/4s - climaxes which suddenly

burst forth with little or no build-up, as if the composer, all

at once, brimmed over with expressive joy to which he must give

vent. For the main impact of this ecstatic music is a joyous sound

- and in quieter moments wrapt in a mood of contemplative peace.

Marx’s Nature Trilogy was written between

1922 and 1925 - and its constituent parts are here performed together

(It had hitherto been played - though not in the benighted U.K.)

as separate pieces of a tone-poetical nature - no reason why not,

since it seems there is little by way of thematic links between

the three sections, and, as played here, it is soon realised that

this is not a symphonic whole in the accepted sense). The first

section is a gorgeously opulent symphonic poem whose subject is

a moon-washed night, untroubled by the dark imagery that shadows

Schoenberg's Verklärte Nacht (Marx was a strong opponent

of the Schoenberg circle - and although perhaps disliking the

programme behind the Schoenberg work he must surely have admired

the rich texture of the Sextet, and probably the Gurrelieder)

There is little doubt about the influence of

Debussy which Marx happily acknowledges in the second of the three

sections - the Idylle. The impressionism is no less seductive

than that of L’Après-midi, even if the sexual imagery

of the faun s perhaps replaced by a kind of pantheism embodied

in priapic wood-creatures. It is not the Debussy of La Mer

a work in which no human element is involved. Nor is it mere picture-postcard

music although perhaps closer to the Nocturnes of 1899.

Its joy in Nature is a kind of mythic pantheism in Castelli

Romani and most evident in his last major composition Verklärte

Jahr - settings for voice and orchestra of German poets and

his own words:

"And near the marble ruins which albeit insensitive

Tell you better than men what youth, desire and

impermanence are."

Yet somehow this music is far removed from the

neurotic morbidity of Schoenberg and his circle, its yearning

born of the awareness of the impermanence of that beauty, yet

underneath the promise of reburgeoning Spring.

Marx's music, just as brazenly romantic has a

lot in common with that of Bax here recalling immediately, in

the opening bars of the first section the development of the Sixth

Symphony's scherzo theme as it leads [fig. 36] into the Epilogue,

equally ecstatic and curiously in the same key. Indeed the central

tune of this might readily have come from Bax's pen - recalling

Cathleen ni Houlihan. And there are many felicitous details

of orchestration in common.

Marx's world is also very close to Delius's -

and in the central Idylle, deep in the wooded garden, is

the song of the cuckoo - another element of Spring. Marx is said

to have composed mostly during the summer months - but it is the

Recurrent Spring that is the motive force in his work.

This element of awakening Spring seems to crystallise

in the opening bars of Marx’s A major Violin Sonata:

A motif - idée fixe - leitmotif - call

it what you will - that also appears in the first section of the

trilogy [at 6.10] and significantly returns in the very opening

bars of the third Frühlingsmusik. It also pervades

the Violin Sonata, and in the first bars of the Quartetto Chromatico

(in these last instances, in the same key). Surely despite

the intimation of regret, or melancholy in the falling 7th, this

motif must in some way have a connection with Spring?

But all is not excess. The Suite for cello and

piano acknowledges its ancestry in Schubert and Brahms - and its

powerful athleticism is echoed in the chamber music of Ireland

and Bridge. Yet in. the formal constrictions of Fugue (such as

that in the A major Violin Sonata, and in the Prelude and Fugue

for piano solo) Marx contrives to invent eloquently melodic subjects

such as few composers - the other exceptions are certainly Reicha

and Paderewski - can produce.

So what do we know of Marx? Sadly little enough

despite the vastness of his oeuvre. He was a renowned teacher,

philosopher and author of treatises on harmony and counterpoint

(which would seem to counter challenges to his supposed vagaries

of form). He was an implacable enemy of the second Viennese school

- as brazen a romantic as was Bax (Marx only died in 1964) less

of a 'wunderkind' than Korngold (with whom he has been too often

compared). He wrote some of the loveliest lieder since Schumann

by whom his song writing is certainly influenced (the Liederkreis)culminating

in the cycle' Verklärte Jahr.

The songs and piano music belong principally

to the 1920s - and until 1930 or so he wrote largely for the orchestra.

Latterly he devoted himself to chamber music - and it is hoped

that, as well as the orchestral music ASV will record these mature

compositions.

For the moment therefore, we hear possible echoes

of Ravel (La Valse?) Strauss, Korngold, Reger, Franz Schmidt,

Respighi, Zemlinsky - and other near-contemporaries. Yet, until

a wider experience of this composer is heard it is scarcely possible

to be specific - and we may for the moment conclude, as is so

often the case in this century, that these 'influences' are likely

as not mere 'clippings into the common pot' of the musical language

of the day (The 8th, 9th and 10th bars of the piano solo' Arabeske'

are echoed in the music of Billy Mayerl?) suffused as it is with

the exoticism that travel and communication (especially film and

the media) has brought.

This is certainly music to wallow in - such experiences

are rare enough that satiety is unlikely! It is a fine and welcome

recording, an excellent performance as far as we can judge without

a score - and there is no doubting the sincerity of the players

and their committed conductor.

I look forward eagerly to ASV's future Marx productions

- and hope that somewhere in the dust the Herbstsymphonie

will materialise.

Colin Scott-Sutherland

see also review

by Rob Barnett

WEB REFERENCE

An outstandingly well presented and detailed

Marx site: www.joseph-marx.org