Following the phenomenal success of Cavalleria

Rusticana (1889) operas flowed rapidly from Mascagni’s pen for

about a decade: L’Amico Fritz (1891), I Rantzau (1892), Guglielmo

Ratcliff (1895), Silvano (1895), Zanetto (1896), and Iris (1898).

With the arrival of the 20th Century the pace began to slow down:

Le Maschere (1901), Amica (1905), Isabeau (1911), Parisina (1913),

Lodoletta (1917), Il Piccolo Marat (1921), Pinotta (1932) and

finally Nerone (1935), largely a reworking of a much earlier piece.

Mascagni himself was convinced that the public’s obstinacy in

preferring Cavalleria Rusticana was an injustice. Criticism of

the earlier works has tended to centre on clumsy libretti and

patches of weaker inspiration, while real controversy has surrounded

the later pieces. Here, we are told, Mascagni tried to dress up

as a modern, flirting with dissonance and ungainly vocal declamation,

at the expense of his natural melodic gifts. He was dabbling in

things beyond his reach. The case for the defence was put by,

among others (but not very many others, alas), William Alwyn,

who was convinced that Il Piccolo Marat was among the greatest

music dramas of the 20th Century, to be spoken of in

the same breath as Wozzeck.

As regards the implication of incompetence, I

do not see how anybody could listen to the records under review

and deny that Mascagni knew exactly what he was doing. His handling

of the large orchestra and of vocal declamation is masterly, while

each act has a satisfying shape and moves to its end without wasting

time. To test the truth of Alwyn’s assertion it would be necessary

to experience the opera in the theatre as well as to live with

a recorded performance for a certain length of time, but my initial

reaction to this set is that he could well be right.

If today we are obliged to say "we don’t

know the piece well enough to be sure about it", it was not

always so. In the same year as its first performance in Rome (1921)

it was also heard in Verona, Milan (not La Scala), Pisa and Turin,

as well as in Buenos Aires, Rosario and Montevideo, where the

leading role was taken by Beniamino Gigli. The following year

it was performed in Dresden and Copenhagen. Its foreign career

practically stopped here (it has never been produced at Covent

Garden or in any city of the United States) but between 1921 and

1953 it could boast performances somewhere in Italy in every year

except 1944, 1947 and 1949. It finally reached La Scala, under

Mascagni’s baton, in 1939. After 1953 it was seldom sighted. In

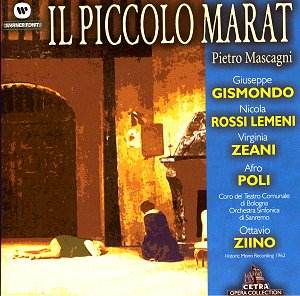

1961 Virginia Zeani and Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, recently (1957) married

and evidently looking for something effective in which they could

appear together, revived it with Umberto Borsò as Il piccolo

Marat, Afro Poli as the carpenter and Oliviero De Fabritiis conducting.

This performance has been issued on Fonè. The Zeani-Rossi-Lemeni

ticket brought about a modest revival, since in 1962 came the

present Sanremo performance, with a different tenor and conductor,

and in 1963 they took it to Naples, Catania and Barcelona. Subsequent

performances of the opera took place in 1966, 1979, 1989 (a Livorno

performance also issued on Fonè) and 1992 (a concert performance

in Utrecht conducted by Kees Bakels available on Bongiovanni and

a run of performances at Wexford).

Set in revolutionary France, Il Piccolo Marat

is a "rescue opera" after the manner of Fidelio, with

a brutal embodiment of evil in the form of the "Ogre".

Among the prisoners in his jail is Princess Fleury, whose son

pretends to join the revolutionaries, the "Marats" (hence

he is known as "the Little Marat") in order to gain

access to her and rescue her. Along the way he falls in love with

the Ogre’s unhappy niece, Mariella, and aims to rescue her too.

The story pivots around the noble figure of the carpenter who,

utterly disgusted at the things he has been made to do (such as

inventing a device for sinking a barge-full of prisoners in the

open river) now works against the revolutionaries. It he who saves

Fleury by slaying the Ogre, and as the opera ends he carries him

off, severely wounded, to the boat where Mariella and Fleury’s

mother are waiting to flee.

It is a satisfying story, likely to remain relevant

for as long as dictators are still with us, and Mascagni has illustrated

it with music of dark and menacing power. Set arias are practically

non-existent, but the declamation itself is melodic as well as

dramatic and the few moments of lyrical expansion are often of

great beauty. Though recognisably the work of Mascagni, he has

brought a touch of steel into his style, and as far as I am concerned

has done so with complete success. I see it as an enlargement

of his range, not a negation of his natural talent.

The opera places very great demands on the singers,

who are required to sustain very long lines in high tessitura.

Moreover, there are four big roles and another two (the mother

and the soldier) quite important enough to sink the ship if done

badly. Fortunately everyone here is equal to his task and quite

frankly, given the state of things today, it is difficult to imagine

any modern recording offering a successful challenge. Little information

is to be obtained about Giuseppe Gismondo (the booklet has a brief

essay on the opera and a synopsis, in English and Italian, and

the libretto in Italian only). I learn that he was "a favourite

of New Orleans for many seasons" so perhaps American readers

will know more than I do. He has a fresh, clear-sounding, very

"tenory" voice, not apparently big but able to cope

with the cruel demands of the writing without showing strain.

Perhaps the sound is a little unvaried, but he makes a fervent,

sincere character out of Fleury.

Born Virginia Zehan in 1925, the Romanian-Italian

soprano included Aureliano Pertile among her teachers and made

her debut in Bologna as Violetta in 1948. Gifted with a particularly

warm, refulgent timbre and a fine technique, she belongs to that

group of sopranos (Carteri, Cerquetti, Gavazzi, Pobbe …) who were

overshadowed by the Callas-Tebaldi rivalry but who would be welcomed

with open arms today. As a matter of fact Zeani was one of the

few who managed to make some impact with Violetta in those days,

a role she sang 648 times. She specialised in bel canto roles,

but she certainly did not lack the heft for Mascagni, for she

sings here with total security and a ringing conviction. It is

also a very expressive performance and for me, quite apart from

the merits of the opera, serious lovers of singing should obtain

the set for this memento of an exceptional singer. She retired

in 1982 and in 1980 she and her husband began teaching at the

Indiana University School of Music. To the best of my knowledge

she is still there.

Nicola Rossi-Lemeni (1920-1991) was born in Constantinople

of an Italian father and a Russian mother. He made his debut in

Venice as Varlaam in Boris Godunov in 1946. In 1950 he was Stokowski’s

choice for the title role of that opera, with which he was particularly

associated, though for some tastes he was excessively histrionic.

His voice is more cavernous than subtle, so it may well be that

we lose out by not seeing him as well as hearing him. But the

character itself is not a pleasant one and he certainly makes

a loathsome villain of the Ogre..

Afro Poli (1907-1988) made his debut in 1930

and in 1932 was chosen to sing Malatesta in the famous Tito Schipa

recording of Don Pasquale. He also sang Marcello in the Gigli

Bohème (1938). Obviously his voice was no longer young

in 1962, but considering that the carpenter in Act 2 is described

as "tragically changed, emaciated, ashen, worn out"

the last thing we want is a bright young voice. He sounds believably

at the end of his tether.

The Sicilian conductor, composer and teacher

Ottavio Ziino was more of a force in Italian musical life than

his meagre discography would lead you to think. A Foundation and

a vocal competition conserve his name. He was no stranger to Il

Piccolo Marat, having conducted four performances of it in Naples

in 1942, and he believed in it enough to conduct it again in 1979

(with Martinucci). He has the large forces firmly under control

and realises the score’s harsh colours, as well as its rare moments

of tenderness, with mastery and conviction. It is a pity we do

not hear his work more closely, for in the Cetra manner the voices

are very much in the foreground. The orchestra is clear, but placed

too far backward. The recording is claimed to be live, in which

case the audience must have been gagged since there is no evidence

of them. I also assume, in the absence of stage noises, that it

was a concert performance without any attempt at "production",

since at a certain point we are told in the libretto that "everybody

breaks out laughing" and nobody does so here.

As I have pointed out, there are three alternative

recordings, which I haven’t heard, one with three of the same

principals from the previous year and two more modern ones which

should at least offer better sound. However, since the present

performances is a very fine one and the sound, with the reservation

made above, is perfectly acceptable, I don’t think you could go

wrong if you want to get to know a neglected and powerful opera,

and you will also hear a little-recorded but important soprano.

By the way, in case you think I’m the world’s

leading expert on Mascagni, I should point out that most of the

above information comes from Erik Bruchez’s wonderfully informative

Mascagni site, a true labour of love which can be visited at www.mascagni.org.

The section devoted to performances of Il Piccolo Marat contains

a strong comment by François Nouvion:

Il piccolo Marat is a tenor opera… The success

of the work depends on a tenor capable of sustaining the high

laying tessitura. It was given well into the 1960s when such tenors

were still available. …. The penultimate revival in Livorno with

the tenors Pinto and Tota alternating the role was a disaster

if one bases his opinion on the live recording made with Pinto.

The tenor role is a part that neither of our "great 3 tenors"

could sing, even in their younger days.

Well, I should have thought that Domingo at least

could have coped, though since his Osaka in Iris was already strenuous,

this would presumably have been more so still. Certainly, no obvious

candidate for a modern Marat comes to mind.

I also learned from this site, rather to my surprise,

that recordings have been issued of all fifteen of Mascagni’s

opera, as well as his operetta Sì, though in many cases

they look to be stop-gaps, made live in provincial Italian opera

houses.

Christopher Howell