The

tepid applause for the two principals at the end of this production

says it all. Botha’s Calaf is bland, the voice almost expressionless

and the acting and girth hardly that of a headstrong man sacrificing

and gambling all for the love of an ice maiden. All would

sleep through his ‘Nessun dorma!’ Schnaut, looking like a disorientated

Brünnhilde, rather than a Puccini heroine, is little better,

her high notes insecure, with too much vibrato and her acting

confined to grimaces and holding her head as if something vile

was continuously beneath her nose. Not so for Christina Gallardo-Domas

whose sweet lyricism drew for her Liù the warmest applause.

Robert Tear was in fine authoritative tone as Altoum the hapless

Emperor. Tear, aged 63, at the time of this 2002 recording is

still in excellent voice. Daniel, Ombuena and Davislim were all

good as Ping, Pang and Pong but were practically defeated by their

ridiculous costumes (more about the visual aspects of this production

below) in their sentimental Act II trio when they dream of peace

at home on their estates, even though against a floral backdrop.

My

highest marks are reserved for the beautiful playing in every

department of the Vienna Philharmonic under the baton of Gergiev.

I would just single out, as examples of their virtuosity and subtle

sensitivity, their playing of Puccini’s lovely moon music in Act

I, the music for Ping, Pang, Pong’s trio mentioned above and the

Act I climax as Calaf strikes the huge gong and the Processional

of Act II. Gergiev’s expressive interpretation subtly underlines

the mechanisation of Pountney’s conception, in Act I, without

sacrificing the essential Puccini

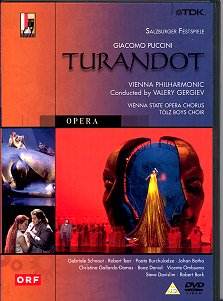

This

is a remarkable production - a modern conception as one can deduce

from the booklet cover illustration above. One first sees that

huge head in back view during the lovely Act I choral ‘Perché

tarda la luna’ lit appropriately blue and sylvan. The huge head

turns full face then splits down the middle to reveal Turandot

atop of a 9 metre train. The explanation in the notes runs – "Her

almost pathological hatred of men is … the reason she hides behind

a mask of rejection and inhumanity to protect her vulnerable psyche."

It must be said that Brian Large’s low camera angle looking up

at her as though from the pits of hell (low foreground coloured

blood red with the uniforms of the automatons) during the setting

of her three riddles is brilliant and quite terrifying theatre.

This Turandot is set in a totalitarian state populated

by robots, standing on tiers of scaffolding with large gear wheels

and looking like rows of ‘Edward Scissorhands’; robots that only

become human when Turandot surrenders to love. This mechanical

scenario just about kills the atmosphere of the lovely Act I moon

chorus rendering it grotesquely incongruous. Other costumes are

equally weird. Ping, Pang and Pong, for instance, dressed in plastic

macs have spanners and saws etc for arms.

Luciano

Berio’s ending is nicely integrated into the structure; the music

anodyne, and mercifully not anti-Puccini. The idea to ease and

make more appealing the transition from the sacrifice of Liù

to the declaration of love and surrender of Turandot is good but

it only partially succeeds here. The sight of the two principals

symbolically washing their guilt by bathing the body of Liù

lying on what looks like a morgue trolley with tin bowl is only

a few steps from Fawlty Towers farce.

Disappointing

performances from the two principals in an eccentric modern production

that is only partially successful mainly due to Gallardo-Domas’s

nicely expressive Liù and the beautiful playing of the

Vienna Philharmonic under Gergiev.

Ian

Lace