The

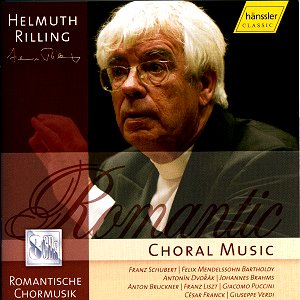

German conductor, Helmuth Rilling was born on 29 May 1933. To

celebrate his seventieth birthday Hänssler Classics, for

whom he has recorded for many years, offer this box of 8 well-filled

CDs for the price of five.

Two

choirs dominate these recordings, as they have dominated Rilling’s

career. As long ago as 1953 he founded the Gächinger Kantorei,

initially a forty-strong group, which took its name from the village

of Gächingen, just outside Stuttgart. Since then the group

has developed and can now muster a singing strength of between

24 and 100 or more, depending on the forces required for a particular

work. Since 1965 the choir has appeared regularly with the orchestra,

the Stuttgart Bach-Collegium, an ensemble which plays on modern

instruments and which, therefore, is just as well equipped to

perform romantic or modern music as it is to play the works of

Bach and his contemporaries. In 1970 Rilling’s career expanded

significantly across the Atlantic when he co-founded the Oregon

Bach Festival, with which he is still very closely associated.

I

think that anyone listening to these discs will be impressed by

Rilling’s obvious skill as a choral conductor. He strives, successfully,

for clarity of texture, attention to detail (especially in the

matter of dynamics) and unanimity of attack. His choirs are unfailingly

well balanced and the sound that they make is pleasing. One never

feels that the tone is being forced. The soprano line is generally

bright without descending into shrillness. The altos avoid any

suggestion of "pluminess". The tenors have a

good, bright, sappy tone and the bass line is firm without muddiness.

But there’s more to these performances than technical excellence.

Consistently I felt that Rilling is able to communicate that he

loves the music he is directing.

The

first two CDs give us a chance to hear him directing performances

of Schubert on both sides of the Atlantic. However, the oratorio

Lazarus offers few opportunities for the German

choir to show their mettle since the work as presented here contains

but two choruses. Schubert left the work incomplete, literally

breaking off half way through the seventh number of part two,

an aria for the character of Martha. When Helmuth Rilling recorded

the work in 1996 he commissioned the composer Edison Denisov to

write a completion of the oratorio. Denisov’s additions have been

omitted here. I have to say that the work does undoubtedly have

its longueurs. As you’d expect from such a vaunted composer

of lieder there is much easeful melody, and some drama, in the

succession of arias but the piece didn’t consistently engage my

attention (the lack of a printed text didn’t help) despite the

dedicated performances of Rilling and his fine team of soloists.

We

are on much more familiar ground with Schubert’s fine Mass

in A flat, recorded in the USA. With the benefit of the tighter

structure imposed by the text of the Ordinary of the Mass Schubert

produced this time a much tauter and effective piece. The performance

is very good indeed with excellent soloists and a fine contribution

by the choir. The robust passages, such as the sturdy fugues,

come off well but it is the softer passages that especially catch

the ear.

The

coupling for the Schubert Mass is Mendelssohn’s setting of Psalm

42.It was only recently that I gave a warm welcome to Rilling’s

reissued recordings of Mendelssohn’s two great oratorios, Paulus

and Elijah. Here, in this shorter piece, he exhibits

once again his credentials as a doughty champion of Mendelssohn.

In this work the fingerprints of the composer of Elijah

are all over the score. The bulk of the solo work is given to

the soprano and, happily, Sibylla Rubens excels. Hers is essentially

a silvery voice but she is more than capable of injecting a touch

of steel where required. This may not be a masterpiece on the

level of Elijah but Rilling makes out a very good case

for it.

A

disc and a half are devoted to Dvoŕák’s Stabat Mater.

At first I feared I wasn’t going to like the performance but

as it progressed I warmed much more to it and if any listeners

have similar initial feelings I’d encourage them to persevere;

it’s worth it. I think the trouble at the start is that Rilling

is too pensive. His performance doesn’t have quite the same supple

flow that we find in Rafael Kubelik’s 1976 DG version. Nor does

Rilling’s orchestra have the tonal resource possessed by the Dresden

Staatskapelle for Giuseppe Sinopoli in his dramatic account (also

DG, 2000)

Overall,

Rilling’s is rather a soft-grained approach (an impression which

may be magnified by the recording itself which I found was best

played back at a slightly higher level than usual.) He has a very

good solo quartet at his disposal (though I have a marginal preference

for Kubelik’s team) and they are well integrated as a team as

is clear, for instance, in the ‘Quis est homo’ quartet (though

here I find more urgent singing in the Kubelik version.) In ‘Fac

me vere tecum flere’ tenor James Taylor is outstanding, producing

lovely, effortless singing with a heady and plangent tone (CD

3, track 6, from 1’06"). The duet, ‘Fac, ut portem’ finds

him and soprano Marina Shaguch combining well and the ‘Inflammatus’

is sung by Ingeborg Danz with warm, full tone; she gives a fine

account of this important solo. The remaining soloist is Thomas

Quastoff and, as you might expect, he provides a solid foundation

for the quartet and is suitably imposing in his solo, ’Fac ut

ardeat cor meum.’

The

choral contribution, though recorded a little more backwardly

than I would have liked, is excellent throughout and Rilling encourages

attentive, well-phrased singing from his American choir. They

are effectively supported by the orchestra. All in all, this is

a very good performance of the work.

This

collection also includes a large helping of Brahms’s choral music.

First comes Schicksalslied and straight away Rilling

demonstrates that he is a fine Brahms interpreter. The burnished

orchestral introduction suggests a performance of distinction

is to follow and so it proves. As compared with the recording

of the Dvoŕák the choir is, to my ears, more forwardly placed

in the aural picture and this is wholly beneficial, the more so

since they sing so well. The glorious, lyrical opening is most

beautifully rendered and later on the turbulent music really has

drive and purpose. We end as we began with lovely orchestral playing

in the radiant postlude.

The

performance of Nänie, which comes next, is

just as fine. This work is blessed with long, undulating choral

lines though these are not easy to sustain. Rilling and his singers

shape them beautifully, not least in the heart-easing coda. The

third piece in this group contrasts nicely for Gesang der

Parzen is a more dramatic piece than its companions. Rilling

gives it a strong, purposeful reading and his choir reward him

with some fervent singing which is ably supported by the orchestra.

One passage which particularly caught my ear was the section (CD

4, track 6 from 8’50") where a quite splendidly projected

tenor line dominates the choral texture. A few moments later the

sopranos take up the same material to equally good effect. It

is instances like this which really prove how good a choral trainer

Rilling is. His choir make it all sound so natural and easy, the

hallmark of a really well prepared ensemble.

Disc

five is devoted entirely to Brahms, containing a performance of

his most substantial choral work, Ein Deutsches Requiem.

Comparing Rilling’s account with two long-established personal

favourites of mine (Rudolf Kempe’s 1955 account and Otto Klemperer’s

stoic reading, set down in 1961, both EMI) I found that the older

versions were preferable on some counts (mainly minor points)

but in other respects Rilling more than held his own.

Gilles

Cachemaille is Rilling’s baritone soloist. His is a fairly light

voice which is well produced and which falls pleasingly on the

ear. I must say that he is nowhere near as characterful as Dietrich

Fischer-Dieskau, who appears in Rudolf Kempe’s devoted version

and later reprised the role for Klemperer. However, the fluent

tempo chosen by Rilling (quite close to Klemperer but appreciably

quicker than Kempe’s) complements his soloist’s vocal style very

well.

The

soprano soloist, Donna Brown, sings with great poise in ‘Ihr habt

nun Traurigkeit’. However, she must yield to Elisabeth Grümmer’s

radiant ecstasy for Kempe. I put on that version intending just

to do a couple of spot comparisons and ended up listening to the

complete movement and being deeply moved by it – yet again!

The

chorus makes a fine contribution and the fact that they are German-speaking

gives them something of an advantage over Klemperer’s (excellent)

Philharmonia Chorus. In the fourth movement, ‘Wie lieblich sind

deine Wohnungen’ the effectiveness of Rilling’s preparation is

very evident as his choir produce some really luminous tone for

him. In the sixth movement, ‘Denn wir haben hie keine bleibende

Statt’, the choir achieves a real sense of quiet mystery at the

start of the movement, better conveyed than I’ve ever heard before,

which is done through sheer discipline and dynamic control. Thus

when they sound the Last Trumpet later in that movement, the moment

is all the more dramatic. The final movement is thoughtful and

is distinguished by a good deal of quiet, reflective singing.

Overall

this is a very fine and successful performance of this masterpiece.

Whilst it doesn’t dislodge the Kempe performance in my affections,

still less the Klemperer, it’s a version to which I’m sure I will

return with great pleasure in the future.

Like

Brahms, Bruckner is well represented in this anthology. Strangely,

at the same time as reissuing Rilling’s recordings, Hänssler

have licensed them to Brilliant Classics and the Brilliant box

containing these performances, and others, was recently reviewed

here by Robert Hugill. While generally welcoming these performances

he issued a cautionary warning about a lack of Brucknerian structure,

feeling that this was more apparent in the classic DG recordings

by Eugen Jochum. Having compared the readings myself I should

say that in general I agree with him, especially as regards the

great F minor Mass.

In

that work I found that in general Rilling is very successful in

the more extrovert passages. It’s in the slower, more profound

sections that Jochum’s much greater experience of conducting Bruckner’s

symphonic music is evident, I feel; he knows instinctively how

to keep the slow music on the move. Thus I find a much greater

sense of purpose in Jochum’s reading of the ‘Kyrie’ where his

speed is noticeably quicker than Rilling’s but with no sense that

the music is being hurried.

In

the ‘Gloria’ the opening bounds along jubilantly in Rilling’s

hands and he almost matches Jochum for fervour. However, when

the music slows (for example at ‘Qui tollis’) Jochum is stronger

and less inclined to linger. Again, the start of the ‘Credo’ is

splendidly festive under Rilling who, characteristically, observes

the important dynamic contrasts accurately. However, later I found

that I didn’t care very much for the way his tenor, Uwe Heilmann,

sings the cruelly exposed solo at ‘Et incarnatus est’. Here Ernst

Haefliger (for Jochum) is superb. The ‘Et resurrexit’, one of

the most memorable passages in all Bruckner, blazes superbly (CD6,

track 3, 8’49") and indeed the remainder of the movement

is very good. The brief, rarefied ‘Sanctus’ also comes off very

well. The soloists have a key role in the ‘Benedictus’ and Matthias

Goerne’s strong but velvety voice is especially effective but

I’m sorry to say that the tenor’s vocal production again sounds

tight and effortful. Indeed, Goerne is really the only one of

Rilling’s quartet who is on a par with Jochum’s impressive team.

The ‘Agnus Dei’ comes off quite well but I feel that Jochum finds

just a bit more spirituality and mystery.

There

are many very good things in Rilling’s performance of this Mass

and it will disappoint no one buying the set but I concur with

Robert Hugill that Jochum has an edge. However, I find that Rilling

turns the tables in the E minor Mass. In the opening ‘Kyrie’

Rilling has a touch more forward momentum than Jochum. Crucially,

Rilling’s choir is much better at sustaining the long notes which

are such a feature of the music. There is a fine sense of grandeur

at the start of the ‘Gloria’ where, as so often in this whole

set, all the choral lines are clear. Once again I found myself

admiring the quality of the choral singing and the degree of control

in the quieter passages. This is also true of the ‘Credo’ where

both the ‘Et incarnatus’ and the ‘Crucifixus’ are superbly sustained

and tuned. Equally, the confidence of the ‘Et resurrexit’ is splendidly

conveyed.

The

‘Sanctus’ has the chaste purity of Renaissance polyphony and is

splendidly sung, the movement ending in a magisterial affirmation.

The prayerful dignity of the ‘Benedictus’ also comes across beautifully

in this performance. The concluding ‘Agnus Dei’ is an extraordinarily

affecting movement and I share Robert Hugill’s enthusiasm for

it. Rilling and his team do it full justice, sustaining a mood

of rapt intensity in a performance which is quietly overwhelming.

This is a quite splendid rendition of this Mass which, by a whisker,

I prefer to Jochum’s classic reading, not least because Rilling

is given a better, clearer recording and obtains even better choral

singing than does his distinguished rival.

The

other Bruckner offering is the brief but powerful setting of Psalm

150. This is a splendid, majestic piece, which benefits

here from some spirited singing and playing though, for once,

I found the choir’s words rather hard to hear. The soprano has

a brief but fearsome solo and here it is effectively sung by Pamela

Coburn, a singer who I don’t recall hearing before.

Discs

seven and eight include extracts from two substantial oratorios,

both of them taken from complete recordings by Rilling. Neither

Franck’s Les Béatitudes nor Liszt’s Christus

are all that frequently heard these days and so it’s good to have

a chance to hear some of the music. (In fact Hänssler have

licensed Rilling’s complete recordings of both works to Brilliant

Classics and both have been reviewed recently on this site.) Both

works are essentially a series of tableaux rather than narrative

in nature so little is lost by presenting extracts in this way

and the Liszt Stabat Mater is especially well suited to

separation from the context of the main work.

Unlike

composers such as Rossini or Dvořák, Liszt sets the text

of the Stabat Mater as one single, through-composed

piece, albeit one with several clearly defined sections. For the

most part the setting is subdued ("more than a little ascetic"

as the notes would have it) though it does contain a few big moments.

Liszt eschews lengthy solos but his quartet of soloists still

plays a major role, often singing as an ensemble. Rilling’s quartet

contains no weak links and, importantly, they blend together well.

The performance features another excellent contribution from the

choir and from the orchestra too (including an important role

for a harmonium.) The only criticism I have is that the chorus

don’t articulate their words too clearly, which is something of

a snag as the Latin text may not be familiar to all listeners.

That said, the reading is committed and eloquent. I have to confess

that Liszt is very far from being a Desert island composer so

far as I’m concerned but I enjoyed this Stabat Mater considerably.

The

three extracts from Franck’s oratorio are also very effective.

The shortest piece is the Prologue which consists primarily of

a tenor solo. It’s not clear from the documentation which singer

is singing here (or elsewhere for that matter) but I suspect it’s

Keith Lewis. Whoever is responsible sings nobly. Though the oratorio

is often described as a contemplative work this description is

belied by the other two excerpts offered here for both include

a good deal of vigorous music. The choir rises to the occasion

very capably (as does the orchestra) and their singing is full-toned

and well articulated throughout. The dynamic range of the chorus

is wide and there’s plenty of contrast as a result. The solo singing

is also of a uniformly high standard. I thought Gilles Cachemaille

had just the right kind of elevated voice for the role of Christ

and the fine soprano solo in ‘Blessed are those who suffer persecution’

(CD 8, track 6) is very well done by Diane Montague. The one slight

disappointment is that at the very end of that piece (the conclusion

of the whole work) the organ is slightly, but noticeably, out

of tune. For those reluctant to invest in the full work these

extracts give a good flavour, I think, and I’m glad that they

have been included, especially since Rilling’s name is not immediately

associated with Gallic music.

Two

Italian rarities to conclude with. Puccini’s Motetto (CD

8, track 1) was written when he was just 19 and was composed for

the feast day of the patron saint of his home town of Lucca. According

to the notes it "fairly gushes with fresh italianità’

(sic). I don’t know about that. It consists of a rather

blatant opening and closing chorus which frames an extended baritone

solo. This is quite pleasing and, unsurprisingly, is indebted

to Verdi. Matthias Goerne sings it well. According to the notes

Helmuth Rilling "wrenched [the piece] from obscurity"

in 1992. I have to say that it strikes me as little more than

a curiosity and a trifle which does not really add to our understanding

of Puccini.

The

Verdi item is another matter, however. This ’Libera me’

had its origins in an aborted project devised by Verdi in 1868

in response to the death of Rossini. He proposed to his publisher,

Ricordi, that thirteen leading Italian composers should each contribute

a section of a Requiem in Rossini’s honour. Verdi and his twelve

now- forgotten colleagues duly produced their composite work but

a variety of political and financial problems meant that it was

never performed until Helmuth Rilling mounted a performance of

the complete work, from which I believe this recording derives.

Though the composite Requiem languished in Ricordi’s vaults Verdi

later recycled his contribution into his own Requiem. The

final version of the ‘Libera me’, which we know so well today,

differs in quite a few respects from the original version as recorded

here. The differences chiefly lie in the soprano solo line but

among the other, noticeable changes, the celebrated ‘thwacks’

on the bass drum are absent from the ‘Dies Irae’ and at the end,

the sotto voce recitative ‘Libera me, Domine’ is given

not to the soloist but to the choral basses. As a fascinating

first draft this is most interesting to hear. Not everyone may

care for the rather histrionic soloist (I don’t) but the performance

as a whole is very good indeed and offers an interesting conclusion

to this survey of Rilling recordings.

The

documentation accompanying this set is a bit basic. The notes

are not especially helpful and, as translated at least, are somewhat

fulsome. No texts or translations are provided which is a bit

of a handicap in the less familiar pieces. I expressed a very

slight reservation about the recorded sound in the Dvořák

Stabat Mater but the recordings as a whole are very good

indeed. As I hope I’ve made clear, the standard of the performances

is uniformly first class.

This

set is a handsome tribute to a distinguished choral conductor.

It contains many very fine performances and I’m sure it will give

great pleasure to collectors, as it has to me.

John

Quinn