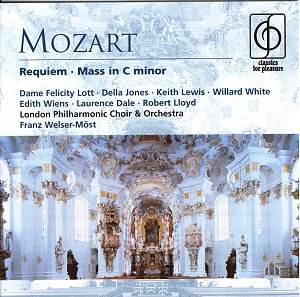

Franz Welser-Möst’s period as conductor

of the LPO was widely regarded as a mixed blessing. However, much

of the criticism levelled at him at the time was unfair, not to

say a little stupid. That he is a conductor of real flair and

talent there is little doubt, and this two-disc set is testimony

to that. These are not by any stretch of the imagination ‘period’

performances, for they use a large orchestra playing modern instruments,

and a big, full-throated chorus – the London Philharmonic Choir

on top form. Certainly not to everyone’s taste, then; but of their

kind, they are well worth hearing.

The coupling of Mozart’s two greatest torsos

seems an obvious one, and I was a little surprised to discover

that there didn’t seem to be another one in the current catalogue

(unless, of course, you know different….!). Of the two, the C

minor is probably the more convincing in the form it has come

down to us. The booklet note discusses briefly but lucidly the

mystery surrounding the work’s incompleteness, which is too complex

to go into here. Suffice it to say that the Robbins Landon edition

used here is strict in confining itself to nothing more than those

sections which exists in the autograph, namely the opening Kyrie,

the Gloria, the Credo up to the Et incarnatus,

concluding with the Sanctus, Benedictus and Osannas.

It is an overwhelmingly powerful utterance, and

represents a staggering achievement for a 27 year-old. This performance

gives it the full works, the opening Kyrie very slow

but darkly dramatic, its chromatic complexities drawn out to superb

effect. The one serious weakness in the casting of the otherwise

very fine soloists is the soprano I, Edith Wiens. Despite her

sweet tone, she is too self-indulgent. Listen to the rising triplets,

track 1 after 3:23, for example. Needless to say, Mozart asks

for no fluctuation in the tempo at all, let alone this sort of

huge rubato. Unfortunately, here and in the exquisite Et incarnatus,

Welser-Möst indulges her, and allows the already steady tempo

to drag almost to a halt in places.

The Gloria concludes with a long-note

fugue that is like a large-scale version of the finale of the

Jupiter Symphony. It builds to a majestic peroration, with

the resplendent announcement by the tenors of the inversion of

the fugue subject a memorable moment. Throughout, the performance,

though far from subtle, captures the imagination and energy of

this tantalisingly great work.

Meanwhile, in the Requiem, Felicity Lott

gives an object lesson in Mozart singing - flexible and expressive,

yet also disciplined and restrained where appropriate. Welser-Möst

uses the edition by Franz Beyer, made in 1971. In effect, it’s

not all that different from the Süssmayer, which remains

in essence the version many choirs use even today. But it does

have numerous differences in details of scoring, as well as some

subtle additions in the later stages of the work, e.g. the conclusion

of the two Osanna sections.

The finest music is in the first two movements,

the Requiem aeternam and the Dies irae, and I have

to say Welser-Möst and his forces are riveting in the big

choral/orchestral sections. The opening brings wonderful phrasing

from solo bassoon, with the lugubrious sounds of basset horns

and alto trombone colouring the music to wonderful effect, all

excellently captured by the spacious yet clear recording. The

beginning of the Dies irae has never sounded more dramatic,

and the upper soloists in the Tuba mirum characterise their

music well, though Willard White doesn’t to me sound entirely

at home in this music; compared to Robert Lloyd in the C minor

Mass; he seems to find the breathing problematic, and worries

at the music somewhat. Great singer, but odd choice.

Odd how the human memory works; as the Recordare

began, I found myself recalling the beginning Part 2 of Gerontius;

on the surface, there’s not much in common other than the

key. Yet Mozart here has that sense of effortlessly light movement

that Elgar wished to express, and the performers capture perfectly

the serenity of this sublime music. The Recordare movement,

though deeply felt, is really too slow and romantically inclined

for my taste, and the tempo causes the choir, particularly the

sopranos, some problems in the sustaining of controlled tone in

the top register. On the other hand, the singing of the solo quartet

in the Benedictus is a real joy. Willard White certainly

redeems himself here, with some sensitive ensemble singing.

As I say, not to everyone’s taste; you’ll either

fall for these whole-hearted, large-scale performances, or you’ll

hate them; I fell!

Gwyn Parry-Jones