It took me several hours to get through this.

Not, I hasten to add, because it was so boring I had to keep stopping

and starting again, but because, while I found plenty to enjoy

in each aria, a little voice inside me kept saying, "but

Iíd like to hear how so-and-so manages this or that part".

And so out came the CDs and LPs and it turned into a dayís work.

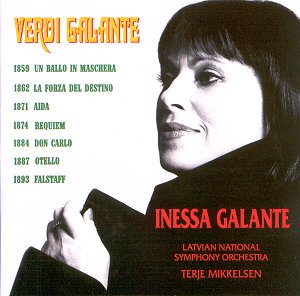

The Latvian soprano Inessa Galante has a splendid

voice, warm and rich and ringingly secure in fortes. She can also

float soft pianos, and these have just a touch of flutter which

is at the moment quite attractive so I hope it doesnít herald

any future problems. If you compare her with the young Renata

Tebaldi (in 1950, on Warner Fonit 5050466-2953-2-3) in two of

the arias which call for sustained, soft singing, O patria

mia and the Ave Maria, you will find a regal authority,

a rock-steadiness which was to grant her a career lasting many

years into the future.

Another question is that of style. Galante habitually

links notes with portamento, attacks notes from below and eases

into high notes rather than taking them head on. Now this is all

part of the Verdian style (at least some of the portamentos are

in the score), and if you listen to the very clean rendering of

Morrò, ma prima in grazia by Margaret Price, abetted

by Georg Soltiís ascetic accompaniment, you are likely to think

so much the better for Inessa Galante. But these devices, like

ornamentation in baroque music, are effective in inverse proportion

to the extent to which they are used. A comparison of the passage

Imprecherò la morte a RadamesÖ a lui chíamo pur tanto!

from Ritorna vincitor as sung by Galante and then as

sung by Maria Callas, Leontyne Price and Leonie Rysanek, and shows

that while the latter three are far from "scrubbed clean",

they place their expressive devices more judiciously, maintaining

a better sense of line and a more urgent communication. At times

I feel that Galante is applying these tricks of the trade conscientiously

rather than from inner necessity. Perhaps for this reason why

her drooping portamentos (arguably, Verdiís slurs in the score

mean he wants portamento) in Salce, salce draw attention

to themselves while those of Tebaldi and Rysanek do not.

And yet you could find Tebaldi the more mannered

in this particular piece, for while Galante and Mikkelsen treat

it as a haunting, slow aria (and so perhaps too little differentiated

from the Ave Maria), Tebaldi and Antonino Votto go hell

for leather and give a verismo interpretation which some will

feel more suited to Mascagni than Verdi (but itís thrilling!).

Rysanek and Arturo Basile show it is possible to find a middle

way.

If Iíve dwelt on these matters it is because

I feel that Galante has the voice and the musicality to match

some of the great names Iíve mentioned, so I hope she listens

to them and learns from them. If we make comparisons with contemporaries

rather than Golden Age singers, then I much prefer her to the

bumpy Renée Fleming in the Ave Maria, as I do, more

marginally, to Angela Gheorghiu in Pace, pace mio Dio,

though the latter has the advantage of a superbly urgent accompaniment

from Riccardo Chailly. Heard away from the comparisons, there

is plenty to sit back and enjoy, and only two items fail to make

their mark. In Sul fil díun soffio etesio Galante is unable

to lighten her voice (hear the smile on Marcella Pobbeís voice

in this piece) and in the extract from the Requiem she demonstrates

that she could contribute handsomely to a great performance of

this work if one were to hand but, while the chorus and orchestra

are good, the conductor is unable to stir them to a more than

merely decorous interpretation. At 14í 41" this is more than

two-and-a-half minutes longer than Fricsayís superbly taut DG

recording (with Maria Stader) and even outlasts the spineless

Giulini.

A general feature which emerged from the comparisons

is that an Italian conductor, be he Serafin, Votto, Basile or

other, is unlikely to adopt the lugubriously slow tempi for pieces

like O patria mia and Salce, salce chosen by non-Italians

such as Mikkelsen , Solti and others. From the booklet it can be

seen that opera does not figure largely in the career of either

the Latvian National Symphony Orchestra or of Terje Mikkelsen ,

and while they mostly acquit themselves with competence, this

may explain why the oboe plays, with loving artistry, a hideous

E flat instead of E natural just before the voice enters in O

patria mia. When I was young and innocent I thought conductors

(and maybe producers) were there to sort that sort of thing out,

but itís amazing what some of them donít notice.

The recording is good, in a slightly recessed

way Ė many of my older comparisons had a more exciting presence

Ė and there are useful notes in three languages, but the words

of the arias are not given. I hope my reservations wonít be too

discouraging because I do feel this is potentially a major talent.

Christopher Howell