The

works on the first disc were commissioned by Italian Radio and

first performed in Capri on 15 September 1948.

G.F.

Malipiero's Mondo Celesti for voice and ten instruments

is in two parts, the first being purely orchestral and vastly

superior. It is, at times, extraordinarily beautiful and has a

decidedly religious atmosphere and the sounds of a quiet warm

day. Indeed the music has a heavenly and ethereal quality but

all the music seems to have nothing but an introductory feel.

The voice enters after 6'30" but I did not respond to this singer's

voice as it was, at times, too heavy for a work of such evocation

and contemplation. It needs a lighter and purer voice with an

innocent sound. The simplicity of this amorous music is disturbed

by the dominant soprano. In the instrumental parts there are some

ravishingly beautiful sounds. I have often thought that this piece

would have fared better with a wordless soprano part blending

into the instrumental texture.

The

Milhaud is hugely enjoyable music based on sonatas by the

early French composer Jean Baptiste Anet (1661-1755) who was a

pupil of Corelli and a virtuoso violinist in his own right. I

am not convinced that Milhaud's bringing 18th century music into

the 20th century really works since the spirit of the music is

lost. On the positive side Milhaud eschews all those ghastly and

infuriating ornaments that bedevilled this early music with those

grinding rallentandos that ended movements. Nonetheless the reworking

is sincere and the music is very attractive. Apart from a treble

cut the sound is good, particularly with the string players, and

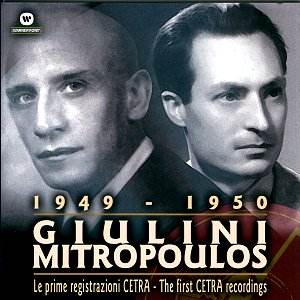

the performance by the young Giulini is excellent. However the

sound is suspect in the fast music particularly the final allegro.

With

the Petrassi we encounter the first really original work

on the disc. There is always a problem with the harpsichord being

swamped by the orchestra and, occasionally, it is here. But all

the various characteristics of the harpsichord are magnificently

caught by this brilliant composer who deserves a major revival.

After all, he is the father of contemporary Italian music. The

opening movement, is episodic but full of interest and innovation.

The tripartite adagio is quite superb - profoundly moving and

never cloying. It has some subtle punctuation and evolves with

great logic and coherence. There is a lachrymosal feel and occasional

bursts of brief anger and the shaking of bones. It is beautifully

written. The vivace is playful rather that quick and sometimes

curiously subdued. It is a clever jibe at the tedium of academica

- its predictability and restrictions. This work is such a contrast

to the marvellous Concertos for orchestra and Petrassi's unsurpassed

choral music.

Roman

Vlad is a Rumanian composer born in 1919. He studied in Rome

with Casella. He is the author of a book on Stravinsky and came

to the Dartington Summer School in 1954 and 1955. His is a rare

talent but he is ignored. This Divertimento is the best work on

these two discs. It may not have the immediacy of the Milhaud

but is a better piece. The opening allegretto is quick and conjures

up a movie scenario of a quiet but strong wind bending trees.

There is a lot of drama here and Giulini is on top form. The second

movement is a theme and five variations namely a march, a waltz,

a galop, an ostinato and a final largo. The movement opens with

a rising tension that is really very well worked and effective.

The march is sardonic and highlights the pomposity of the action

with sneers and a terrific menace. The waltz is a wonderful send-up

of another type of pomposity, social arrogance when overdressed

members of society in the city's season indulged themselves. The

slushy sickly music of the waltz is also lampooned in its attempts

to conceal the sleaziness of many such ‘society’ occasions. The

galop is fun with hints of A-hunting we will go but what

follows is some of the creepiest music you will ever hear. With

apologies to Bernard Herrmann and his excellent score for the

Hitchcock film Psycho but with Vlad's music I feel that

I am approaching Bates' Motel in the dark and driving rain. Scary

music. The final Largo has a grandeur but, thankfully, devoid

of that sickly Edwardian pomposity. The final movement is a Rondo

brillantly written with layers of sound, original scales and dodecaphonic

styles as well. This is an example of the most excellent craftsmanship.

It abounds in an originality that is totally satisfying.

I

suppose that those who will appreciate this work are those who

are musicians who can detect and realise the sheer genius of it.

The

second disc is of orchestral music conducted by Mitropoulos.

Malipiero

contemplated writing a work based on a poem by Antonio Lamberti

and which was written in a Venetian dialect. The composer often

declared his love for Venice but from 1933 he toyed with this

project. Its realisation was in 1948 but without a vocal or choral

part and it was entitled Symphony of Songs.

The

symphony begins with a short allegro. Like much of Malipiero's

music it is acceptable but never special or outstanding. The second

movement is marked lento quasi andante and hints at beauty

even if it does not express it fully. It is pleasant enough but

could be called melodic nullity. It is difficult to follow the

structure and direction of the music however glowing it is … which

sometimes it is. The third movement is headed allegro impetuoso

but it is not impetuous. Again it is pleasant and presents

no problems to the listener but, as throughout the symphony, there

is nothing substantial to grab our attention. There is some choice

orchestration.

The

finale is a long slow movement and it is sometimes beautiful in

a lukewarm sort of way. But it does not come across as a whole

but, rather, as a collection of small pieces of various colours

stitched together into a musical patchwork quilt.

The

symphony is out of balance. In its four movement we have about

eight minutes of moderately paced music and twice as much of slower

music. We must continue to lament that lively and vital music

seems to be lost or a mere rarity today. The wonderful vivacity

and classical structure of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven has, in

the main, long been discarded.

There

is a revered British composer who has a hour long symphony of

which only 9 minutes are brisk.

Looking

at this Malipiero symphony the opening movement is merely a prelude,

the second is a sunny idyll more akin to a tone poem and so on.

The

music is impressionistic and it lacks any drama. It is pleasant

but somewhat inconsequential.

And

so to Alfredo Casella's transcription of the long Chaconne

from Bach's Solo Violin Suite no. 2 in D minor. This is a

movement far too long for the suite in which it is placed. Casella

referred to it as a monumental masterpiece. Well, maybe, but some

say it is trammelled by academic restrictions. However, I do recommend

Hilary Hahn's performance of it on Sony Classics SK62793.

I

am of the view that of the transcriptions of Bach's work. Stokowski

was the best and Elgar the worst. In Elgar's transcription of

Bach's Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, Elgar uses a harp! Casella

is wiser and discerning. He is a far better composer but even

this does not work! There are some good moments which one can

only admire but neither the transcription nor the sound on this

recording does anything. There is a lack of colour but I suppose

that that could be said of the original as it only has a violin

colour.

The

Giulini disc is worth having for many reasons, but I am not so

sure about the Mitropoulos disc!

David

C F Wright