Of

composers great and small I have met or spoken to, Lukas Foss

is the only one I actually had an argument with. I had chided

him for performing Bach on the piano instead of the harpsichord,

but he declined to repent. I was in the audience at the debut

concert of the Improvisation Chamber Ensemble, and at the premier

of Time Cycle with the composer conducting in the original

version (heard here) with improvised interludes by the Ensemble.

Later performances often omitted these interludes.

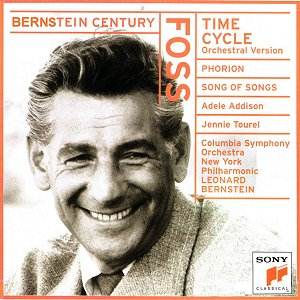

This

disk of Foss’s ‘Greatest Hits’ is very curious in one way: There

are 213 photographs of Leonard Berstein in the program booklet,

and one on the face of the disk — but none of Lukas Foss, which

would lead most casual readers to assume that Foss looked exactly

like Bernstein. He didn’t. One is almost surprised that Foss’s

name is on the cover in bigger print than Bernstein’s, but it’s

turned sideways as if to compensate.

Foss

was one of those composers victimized by the mid-20th century

academic dictum that every work must create and thoroughly explore

a completely original tonal, textural, and stylistic universe,

never to be reused in any subsequent work. The idea of writing

more than one work in the same style was considered akin to hebefrenic

dementia. It was sufficient to discredit a work from nomination

for a Pulitzer Prize (which Time Cycle did win), from public

performance or even from any serious critical attention whatever

merely by citing that it was ‘not original,’ meaning it utilized

stylistic elements which had been used before, even if by the

same composer in his own music. Ironically this was the time that

saw the exploration through recordings and public performances

of the complete catalogues of Haydn, Mozart and Vivaldi, composers

whose approach was at the absolute opposite pole from this idea.

Also ironic was that this demand of absolute originality was interpreted

to require the imitation of Schoenberg, that is use of serial

techniques. Hence Time Cycle. If Foss had flourished 50

years later, I think he would have been a happy neo-post-romantic

composer and written many beautiful works, sounding perhaps like

his Song of Songs, but after producing that masterpiece,

he could never do anything like it again. He’d ‘done that.’

At

the time Phorion was produced, the cliché of building

"original music’ out of fragmentary scraps of quotations

of other composers’ music was also riding high, but fortunately

died out quickly. Phorion stands alone and is quite successful

in its intended depiction of a ‘nightmare about Bach.’

The

composer praises Bernstein for his attention to accurate and thoughtful

performances, and the result is fine music, beautifully played

and recorded. The vocal line of Time Cycle is astringent,

but appealing, the improvised interludes just sound like modern

music, nothing all that special, and the recording captures the

difficult balances very well. The jewel of the disk is the Song

of Songs, its rapturously beautiful melodic lines heartfully

sung by Tourel. You’ll like that one straight off, find yourself

humming the tunes. The others may grow on you as they have on

me over the years.

Paul

Shoemaker