This

is another volume in Sony’s reissued series of Beecham Delius

recordings from the 1950s. Eventyr and the closing scene

from Koanga were included in the Naxos Historical series

of recordings from the 1930s, as were less extensive extracts

from the Hassan music. Arabesque was completely

new to me.

Eventyr

is a fifteen minute tone poem based on "Asbjornsen’s folklore",

a collection of Norwegian folk tales published in 1841. Requiring

a huge orchestra, the work is in that typically Delian rhapsodic

style which demands quite a few hearings before we begin to be

able to find our way around it. The startling moment when members

of the orchestra are instructed to shout is surprisingly tame

here, but otherwise the performance is electric.

Arabesque

is a rich, opulently scored work for baritone, chorus and orchestra.

It is sung to the original Danish text by J.P. Jacobsen, but since

neither the text nor its translation appears in the booklet we

can have no idea of what the soloist, who sings throughout, or

the choir, which has a more subordinate role, are telling us.

A summary of the text at least would have been welcome, but we

don’t even get that. There are certainly many beautiful moments

in the piece, and the soloist sings well enough if with a slightly

tiring vibrato, but an opportunity to help the listener with a

lesser known Delius work has been missed here.

James

Elroy Flecker’s play Hassan or The Golden Journey to Samarkand

was first given in September 1923, having been much postponed

owing to financial constraints. Delius had been commissioned to

compose the incidental music, and the production was successful

enough for an initial run of several months. The music is certainly

atmospheric. From the tender woodwind and harp solos in the opening

piece of this selection to the robust and lively choruses the

music is beautiful in itself and was presumably successful in

the theatre setting. It also manages quite well to evoke the music

of the Arab world without sliding into parody or pastiche. The

Act 3 Prelude is particularly successful in this respect. The

Serenade, an extended violin solo, and the Closing Scene are well

known from other recordings, but this is a more extensive selection

than usual and all the more interesting for that. Some of the

pieces are short, however, and without much idea of the action

they are meant to be accompanying they are difficult to imagine

in context, and the failure again to provide the sung texts means

that we can have no idea what the chorus is singing. Their words

are largely inaudible. Beecham’s performance is magical and definitive,

as it also is of the well known Closing Scene from Koanga.

The names of the slightly wobbly singers are not given, but at

least they are not singing at us from the cellar as seemed to

be the case in 1934.

The

mono sound in Eventyr, from 1951, is the most primitive

of these recordings. There is a certain hardness in the sound

throughout the disc, and also a number of studio noises, pages

being turned and so on, but though it is certainly of its period

the sound no longer gets in the way of the listener’s enjoyment

as I, for one, find it does in the earlier Naxos series.

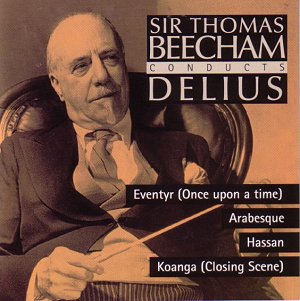

The

booklet is adorned with the same photographs of Beecham as in

other volumes in the series and the accompanying note by Graham

Meville-Mason concentrates on Beecham and his association with

Delius, especially in the recording studio, rather than on the

works themselves, which is understandable given the special nature

of these issues.

William

Hedley