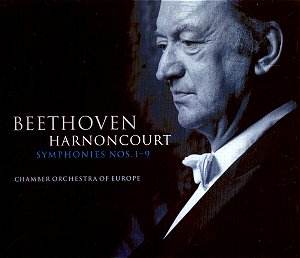

This was the cycle that set the pace for performances

of Beethoven which use modern instruments but which take into

account all that has been learnt by the use of period instruments,

of which Harnoncourt himself was a pioneer. It was greeted with

a great deal of enthusiasm around ten years ago; more recently

the feeling has been expressed that it is not holding up so well

to the test of time.

It is not normally my practice, when listening

to music I know so well, to follow with the score; later on the

oracle may be consulted over specific points. It quickly became

evident that in this Beethoven cycle specific points would be

so frequent that the score was indispensable. These are performances

that strike more for their small details than as a whole. So anyone

who reads my notes below and thinks I am being pernickety, seizing

upon niggling matters and ignoring the overall line, is invited

to look up my other Beethoven symphony reviews on the site (there

are quite a lot) and reflect that, if I adopt a different method

here, it arises from the nature of the performances themselves.

Symphony no. 1

Harnoncourtís liking for rhetoric shows in his

creative treatment of note-values and rests in the introduction

to the first movement. This makes for a more throat-clearing effect

than those performances which proceed at an even tempo. At least

it avoids a drop in tension as the Allegro con brio starts, as

sometimes happens. The main body of the movement bowls along ebulliently

at a swift but not excessive tempo. Not actually memorable but

satisfyingly vital.

In the following movement one is struck by the

swift one-in-a-bar tempo and by Harnoncourtís very deliberate

slurring of the pairs of notes which characterise the main theme:

the first and second note, the fourth and fifth, the seventh and

eighth and so on. It is a moot point whether Beethoven meant these

slurs as phrasing or, as most other conductors seem to

think, as bowing; that is to say a technical matter for

the violinist. The effect is that of a courtly minuet full of

little bows and graces. I am torn between finding it piquantly

charming and feeling that plainer interpretations have found more

depth in the music.

A very fast Menuetto (so-called, we all know

this is a true Beethoven scherzo) means slowing down for the trio.

I find it odd that Harnoncourt plays the wind chords in the trio

so smoothly, completely ignoring Beethovenís staccato markings.

Several conductors have seen fit to repeat the first section of

the Menuetto when it returns after the trio; Harnoncourt repeats

the second section too, and I wonder what his authority is (several

of the cycles on period instruments also adopt this practice).

The finale is basically brilliant, but as early

as bar 8 of the Allegro molto e vivace I wondered why Beethovenís

staccato markings were being made so little of. Admittedly the

coiled-spring Rossini-like staccatos which Toscanini taught us

to accept as the norm may be overdone in the opposite direction,

but this passage vocalises one of my big worries about these performances;

for all their speed, they can be strikingly deficient in actual

forward movement.

Symphony no. 2

In the Allegro con brio of the first movement

Beethoven has marked an unusual number of dynamic contrasts, sprinkling

liberally fortissimos, pianissimos and sforzandos all over the

score. Obviously these have got to be done, but you have to find

the music in them. Much of this is simply brutal, forcing an ugly

sound out of the orchestra. More bullish than ebullient.

The Larghetto shows that Harnoncourt can proportion

his fortissimos to the context in hand when he wants to, and much

of this flows quite nicely. I query whether the march rhythms

starting at bar 128 should dominate the texture when other instruments

have melodic phrases which most other conductors prefer to bring

out.

Another swift scherzo, superbly sprung, resulting

in a slower trio. In theory I agree that the trio should follow

immediately, without any pause, but when the reverberation of

the hall means that the first bar of the trio is completely covered

by the echo of the end of the scherzo, then common sense suggests

that a tiny pause would be in order. Here again we have both repeats

in the scherzo when it returns and if youíre not expecting the

second, your surprise will be all the greater since, thanks to

the reverberation, you wonít notice theyíre playing it till theyíre

about a bar and a half in.

Some terrific playing in the finale, which goes

at a real lick. The magical change to D minor on the rondo themeís

second appearance is rendered null by the reverberation. For all

its vitality, I found this a pretty joyless, jack-booted reading.

Symphony no. 3

A swift first movement has an impressive sense

of continuity, although even Harnoncourt has to yield a little

in second subject territory and he makes a notable rallentando

on the three forte chords that close the exposition (and an even

bigger one at the end of the recapitulation). The effect, in the

context of such a tightly controlled interpretation, is incredibly

pompous, like an old gentleman waving his umbrella to stop a taxi.

There is the expected thrashing at accents, but for all its busy-ness

the performance gives less of an impression that it is getting

somewhere than many others that build it up more patiently. Itís

a very modern hero and one wonders if Harnoncourt is suggesting

that Beethoven had a hidden agenda, rather on the lines of some

of Shostakovichís depictions of Stalin; praising Napoleon to his

face while (for those in the know) sneering at him behind his

back. But if this had been so, Beethoven would not have needed

to scratch out the dedication.

The opening of the Marcia funebre will be the

stuff of an original instruments manís dreams. The strings are

shorn of all vibrato, and instead of building up a long legato

line, as incorrigible romantics from Weingartner to Toscanini

and Klemperer have done, the long notes are allowed to fade away.

Itís rather impressive. Another section which gets an interesting

new look is the fugato starting at bar 114. One of the conductorís

tasks, according to Wagner, was to bring out the melody. Mindful

of this duty, conductors such as Klemperer have brought a rare

luminosity and transparency to this passage by giving each line

its exact weight and guiding the ear towards the part which carries

the argument forward. Harnoncourt evidently believes that the

conductorís duty is to bring out the sforzatos, stabbing at them

without trying to relate them to their context. The passage acquires

a new look since the familiar melodic lines are obscured by a

series of sforzatos arriving from various parts of the orchestra.

Itís fascinating in a way, and if you think itís what Beethoven

wanted youíre welcome to it. What I do find impressive, though,

is the way Harnoncourt holds his tempi steady in the various episodes;

many conductors, Weingartner in primis, find it necessary to move

forward.

In the Scherzo Beethoven made one important change

during the repetition after the trio; the insertion of a few bars

in 2/4 time. On account of this he had to write the whole lot

out again instead of merely writing "da capo". So what

does he do about the repeats? The short first section, the repeat

of which was written out in any case, is maintained, while that

of the longer second section is not. There are similar cases elsewhere

in Beethovenís work and they all point in the same direction;

short first section repeats are maintained on the repetition after

the trio, long second section repeats are not. The scherzo is

so swift that the tempo has to slacken between bars 128 and 150;

that apart it is superb. The delayed upbeats Harnoncourt applies

frequently in the trio are just as mannered and irritating in

their way as was Furtwänglerís romantic dawdling in its later

stages, and perhaps less musical.

The finale, for all its speed, has little Beethovenian

drive (or is that a romantic concept I should try to forget?)

and sounds rather segmented. Given the conductorís ideology, I

would have expected a less protracted treatment of the Poco Andante.

Harnoncourt makes some interesting comments on Beethovenís metronome

markings during an interview in the booklet, and of course we

donít expect slavish observance of them, but surely their relative

values tell us something? This Poco Andante is scarcely faster

than the Marcia funebre, yet Beethoven marked the latter 80 and

the former 108, which is a big difference. By the time we get

to the great horn statement of the "Prometheus" theme

this is the same old romantic Beethoven we have always known.

Symphony no. 4

An impressively mysterious introduction. Maybe

neither Harnoncourt nor his players really believe in the zippy

pace he sets for the Allegro vivace since the tempo keeps dropping

back, picking up and dropping back again until by the time the

exposition is repeated they have settled down to a perfectly normal

speed. Thereafter things go very nicely though I must point out

a couple of oddities. At bar 81 all instruments are marked fortissimo,

but the theme is in the lower strings. If each instruments plays

at his fortissimo all we will hear are the trumpets and

drums hammering away on just two notes, which isnít very interesting.

The normal practice is to mark down the fortissimos on the heavier

instruments and mark up those on the weaker ones in order to bring

out the melodic and contrapuntal interest of the passage. Indeed,

in the old days thatís what people thought a conductor was there

for. Evidently Harnoncourt doesnít agree. Another oddity is his

accenting the staccato string octaves from bar 121 in groups of

three, for which my score gives no authority at all and reduces

the music to mere pattern-making, followed by a pompous rallentando

in bars 133-4. A pity; as I said, much of this is very good, and

Harnoncourt keeps his sforzato accents here in reasonable proportion

to the context.

The Adagio has the long melodies very beautifully

played, but the accompanying figure is very jerkily done, deliberately

intrusive, rather as though somebody is cheekily playing a polka

in the background which has nothing to do with the matter at hand.

I suppose nothing in the score actually says it mustnít be played

like this, and if you like it ...

Virtually every performance Iíve heard of the

scherzo suffers from a tendency to separate the rising and falling

phrases between the wind and strings, creating a stuttering effect.

Harnoncourt avoids this pitfall and this movement is extremely

vital and brilliant. Good, too, that he plays the trio only Un

poco meno Allegro, as Beethoven asks, and not Molto,

molto meno Allegro, as so often happens. This is another case

where Beethoven writes out the return of the scherzo Ė and eliminates

both repeats.

The finale is a triumph of spick and span orchestral

playing. If you think this music has spiritual qualities too,

youíll have to go elsewhere, but itís certainly vital. At bars

305, 307 and 309 Harnoncourt evidently feels that Beethoven hasnít

given him enough accents to jab at, and provides some of his own

(at any rate, they arenít in my Hawkes Pocket Score; perhaps more

recent scholarship has found them). Despite my reservations, this

is the best performance so far.

Symphony no. 5

A thrustful, urgent first movement Ė not a hint

of an unmarked romantic rallentando in the four-note motto theme,

naturally Ė but also finding time for a very clearly phrased second

subject, more meaningful than is often the case. It is noticeable

that in this movement Harnoncourt balances the instruments so

as to bring out the melodies, exactly as I complained he did not

in parts of no. 4. What an unpredictable man he is!

It is a measure of the amount of tempo variation

we usually hear in the Andante con moto that while you will perhaps

find Harnoncourt rather fast at the beginning (it seems a minuet),

many other passages sound "normal" and a few even seem

slow. Harnoncourtís steadiness obviously makes it all the more

telling when Beethoven really does go into a faster tempo for

a few bars near the end. I donít think Iíve ever heard a better

account of this movement.

In the first edition and most subsequent printed

editions, the scherzo and trio are not repeated Ė the trio leads

directly into the mysterious pizzicato reprise of the scherzo

and hence to the finale. Some evidence has been found that Beethoven

originally wanted the scherzo and trio to be played twice. The

first to record it like this was Pierre Boulez, a record that

apparently existed solely to make this point, so uninterested

did the conductor seem in the rest of the symphony, to the extent

of omitting the repeat in the finale, which in the context seemed

quite perverse. Whether the repeat is needed or not, you can hardly

regret hearing such an urgent performance as Harnoncourtís twice

over. The trio is fractionally slower but very fine all the same..

The mysterious reprise and the link to the finale

generate a good deal of tension. When the finale itself bursts

in it has the crudity of a village festival. Harnoncourt may argue

that Beethovenís art is so all-embracing as to find space for

a spot of honest-to-God banality, and he may be right. He also

makes more than most conductors of the dolce marking on

the second subject. One query: when, as in bars 22-25, there are

sforzatos on the offbeats, conventional wisdom says that we have

to accent the beats too, otherwise we will hear not syncopations

but a displacement of the beat and bar-lines. In baroque music

it may often be right to create this sense of displacement, but

I am not so sure that the practice continued into the classical

period. This is a particularly clear example but Iíve been a little

perplexed by several others in all the symphonies up till now.

Still, recommendable fifths are few and far between,

and this certainly is one.

Symphony no. 6

I braced myself for an upfront arrival in the

country. You could have knocked me down with a feather when I

heard the gentle opening! At 13:07 we are in Klemperer (1957)

territory (13:04), but the Klemperer conceals a host of subtle

tempo modifications while Harnoncourt is absolutely steady. The

long crescendos and diminuendos are superbly controlled as are

the dynamic gradations between piano and pianissimo on the one

hand, and forte and fortissimo on the other. Nothing is allowed

to disturb the serene, sublime atmosphere Ė sforzatos are carefully

related to their context.

The Scene by the Brook is swift Ė this time Harnoncourtís

11:59 compares with the 11:56 of Keilberth, who is exactly on

Beethovenís metronome mark Ė but more than any other swift reading

I know, this one succeeds in maintaining a mood of total serenity.

After a while it actually comes to sound slow. Like Weingartner

and Keilberth, Harnoncourt separates the three-note motives in

the accompaniment at the beginning. He also gives exactly the

right weight to the various syncopated notes, for example the

horns from bar 7, so they register but do not intrude.

After so much calm the Merrymaking of the Country

Folk has a welcome vitality and the storm is powerful at quite

a broad tempo Ė which is what Beethoven asked for. Quite a number

of conductors have noted that Beethovenís metronome marking for

the finale is only a notch faster than that for the Brook, and

have made a memorably poetic moment out of the transition from

the storm. Usually, however, they feel the need to move on a little

later. Harnoncourt maintains his slow tempo, returning to the

mood of Olympian sublimity with which he began, if anything winding

down still further towards the end.

In some moods one might wish for a more bracing

approach, but when you want the calmest, most serene Pastoral

imaginable, here it is, a remarkable achievement, and who would

have expected it from this source?

Symphony no. 7

No slackness about the tricky dotted rhythms

in the main body of this movement, which is left to make its point

bluntly but strongly. Though the booklet describes the second

movement as Allegretto the actual feeling is closer to Beethovenís

first thought, Andante. An impressively grave reading, with no

running away in the more lyrical sections. A fast and brilliant

Scherzo has a trio which avoids the romantic dawdling which used

to be common and which would be quite intolerable in a performance

which observes all repeats.

Thus far the performances is mainly a catalogue

of pitfalls that have been avoided; exemplary but not as incandescent

as some (hear the live Beecham from Switzerland on Aura). One

would be grateful for this, but unfortunately the finale falls

into a pitfall of its own. Scrupulously bringing out the sforzatos

on the second fourth-note and then the fourth eighth-note (the

latter are usually lost), Harnoncourt has failed to notice that

thereby the swirling theme in the strings Ė which is the principal

theme of the movement Ė goes unheard. Anyone who knew the symphony

only by this recording would be unaware that the finale had a

theme at all Ė it is reduced to "sound and fury signifying

nothing". In view of the many excellent versions around I

donít see how I can recommend one that gets a whole movement as

wrong as this.

Symphony no. 8

By the standards of period instruments-influenced

performances this has some fairly relaxed tempi (timings are longer

than Norrington, for example), or perhaps it is Harnoncourtís

carefully controlled phrasing which makes them seem so. The first

movement seems more majestic than urgent and is very appealing.

Consistently with the other performances, off-beat accents are

allowed to create the effect of displaced bar-lines rather than

a syncopation. In the case of bars 70-72 I donít see how mere

staccato dots can justify turning the passage inside-out compared

with how we usually hear it.

The second movement is light and graceful and

the minuet flows at a good tempo Ė just as well since we get both

repeats on its return after the trio, about which Iíve already

had my say. The trio is introduced by a surprisingly romantic

ritardando and what follows is delightfully affectionate. With

a finale notable for the beautiful playing of the lyrical second

subject as well as for its overall drive, this adds up to a highly

recommendable version. I should point out that, if you listen

at a neighbour-friendly volume, the dynamic range is so wide that

you might scarcely hear the four note figure which drives the

development of the first movement along, and you might not even

notice the finale has started until the woodwind enter.

Symphony no. 9

The metronome markings of this symphony have

given the original-instruments brigade a field day, since they

vary between the impossibly fast and the unusually slow. Harnoncourt

seemingly ignores the question and produces a fairly traditional

performance, clear and well shaped but without any great aspirations.

It is nice to have it spelt out so clearly which chords, in bars

149-150 of the first movement, are forte and which are fortissimo,

and I shall never again be indulgent towards the conductor who

doesnít notice or canít be bothered. There are similar points

all through. Iím pleased to report that he does not give

the repeats when the scherzo is repeated after the trio Ė for

this relief much thanks.

The slow movement contains a few idiosyncrasies.

On the upbeat to bar 8, why dig in as if there were an accent?

A little later, at bars 15-17, is there any reason why the accompanying

quavers in the strings should be staccato? And if there is, why

do the wind not play in the same way when they have the same music

a few bars further on? But to tell the truth, Beethoven shows

in bars 56-58 that he has sufficient musical knowledge to write

staccato dots when he wants them (did we doubt it?).

The finale is a clear-textured, level-headed

affair, apart from a very exaggerated "poco adagio"

shortly before the voices enter. The soloists are good and the

last solo quartet makes more sense than it often does. But in

the last resort I was underwhelmed, and thatís the last thing

I want when I hear this of all symphonies.

Iím afraid this very mixed bag seems to suffer

from too much of a "historical" approach. It is as if,

for Harnoncourt, the "Eroica" can only be a stepping

stone between nos. 2 and 4, not a revolutionary argument only

superficially related to its own period. And the Ninth, by the

same token, is just the next step up from the Eighth, a bit bigger

and better, but not a great leap into the unknown. Thus two of

the most epoch-making symphonies ever written emerge belittled.

The listener who learns his Beethoven from this set may get the

idea that the composer progressed logically from the First to

the Fifth, touched the sublime in the Sixth and thereafter rather

lost his way (as also in the recent Aimard/Harnoncourt set of

the concerto, where the greatest heights of sublimity are touched

with the Fourth).

Clearly, this is not a cycle I can recommend

in its entirety. It is also being issued on separate discs on

the Elatus label. You should certainly hear 5 and 6, maybe also

4 and 8, and even the Ninth. Or you might look up David Wrightís

reviews of 3, 4 and 5 on the site and reflect that, if we critics

canít find a little more consensus of opinion than this, youíll

just have to forget us and make up your own mind.

Christopher Howell