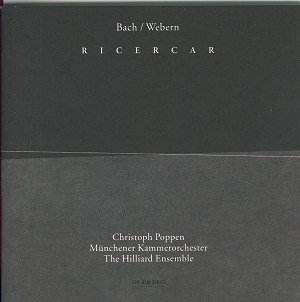

Juxtapositions of ancient and modern can at times

be interesting, but at other times they may clash. This recording

includes works by Bach and Webern, in an attempt to highlight

the "connections" between the two; connections that were, obviously,

in just one direction. ECM describes this recording as follows:

"J.S. Bach's cantata "Christ lag in Todesbanden" provided a context

for "Morimur", the celebrated Christoph Poppen/Hilliard performance

of Bach's "Ciaconna" which revealed "hidden chorales." The cantata

is now at the centre of a new recording focused on connections

between Bach and Anton Webern."

There are several ways of judging a recording

like this. One can look at it from a Bachian point of view, and

judge the Bach works for their absolute value. One can look at

it from a more modern point of view, judging the Webern works

as one should; or one can try and mix the two, offering a point

of view that reflects both types of music. Yet this third choice,

arguably the most appropriate way of looking at such a recording,

is fraught with danger. For not only is the musical language of

these two composers radically different, but the critical language

is as well.

I confess to not only being unfamiliar with Webern's

music, but also to not truly considering it music, at least in

an absolute sense. While I can respect Webern as a composer forged

by his time, I cannot find much in his music that makes me want

to listen to it. The arrangement of his string quartet for chamber

orchestra - a curious undertaking; as if the string quartet itself

were not good enough - is somewhat interesting. It is less grating

than the Five Movements for String Quartet, also arranged for

string orchestra, which sound resolutely random. Yet one is hard-pressed

to find any influence from Bach in this work. Webern's orchestration

of Bach's Ricercar, from the Musical Offering, is also interesting,

but attempts to drain the music of its vital energy and fit it

into the mold of the early 20th century. Others have done worse

things to Bach's music; this arrangement is curious, in its use

of a wide range of instruments. Webern doesn't seem to want the

listener to follow the individual voices of the fugues.

As for the "real" Bach on this disc, the Hilliard

Ensemble realize an interesting interpretation of Bach's cantata

Christ lag in Todesbanden. This performance, using the

one-voice-per-part (OVPP) approach, is ground-breaking. The well-known

cantata is usually performed with a choir, but here the Hilliard

Ensemble fill all the parts with just their four voices. Many

other OVPP recordings of cantatas exist, but few have managed

the unity of sound that the Hilliards provide. While other recordings

feature four soloists, this interpretation features a group of

four singes who have been working together for more than two decades

(note, however, that the performance features three members of

the ensemble with a soprano, Monika Mauch.) The performance is

stunning. The minimal interpretation attests to the validity of

the OVPP approach, but I can understand that this recording will

shock many listeners used to hearing a choir in this work. The

haunting second movement of the cantata, a duet between soprano

and alto, is unforgettable. Fortunately, the orchestra stays out

of the way for much of the music, and does not overwhelm the soloists,

which is too often the case in OVPP recordings.

The final track on this disc is a reprise of

the Bach/Webern Ricercar, which, according to the liner notes,

"will be heard differently now, after everything that has come

before it". Um, right. It certainly is a bit different: 10 seconds

longer than the first track - but other than that I don't get

it. I guess it's a modern thing. I'm too old-fashioned to appreciate

the subtle implications of having the same work twice on a disc.

I apologize for dismissing the Webern works on

this disc so curtly, and perhaps offending believers in another

type of music. The Bach on this disc is very interesting. It would

be nice to hear the Hilliard Ensemble record more OVPP cantatas,

but perhaps without the Webern.

Kirk McElhearn