The accordion has long been an instrument generally associated

with folk or popular music and has only recently been given some serious

attention by contemporary composers, often from Nordic countries. I do

not know whether this situation is due to any particular reason other

than the presence of excellent players who developed a remarkable playing

technique enticing composers to write for them. Haltli’s teacher in Copenhagen,

Magnus Ellegaard, for whom Nordheim and Nørgård composed

several pieces, was one such virtuoso. Haltli and the Finn Matti Rantanen

belong to a younger generation of brilliant players for whom many Scandinavian

composers have also consistently composed. Indeed, all pieces here, but

Lindberg’s Jeux d’Anches, were written for and/or dedicated

to Frode Haltli.

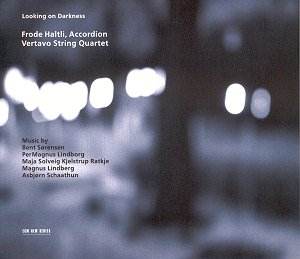

Sørensen’s Looking on Darkness

inspired, so we are told, by Shakespeare’s Sonnet XXVII is a

brilliant study in light and shade, movement and stasis, conjuring up

an often troubled, unpredictable sound world displaying a remarkable

wealth of invention. Lindborg’s Bombastic SonoSofisms,

in spite of its queer and rather enigmatic title (there is nothing bombastic

about this music), is another brilliant showpiece, albeit in a somewhat

more accessible idiom than Sørensen’s sometimes intractable piece.

Schaathun’s Lament is rather more overtly expressionistic

in mood, alternating slow sorrowful moments and angry outbursts of some

energy before ending peacefully on a long-held high note (an incredible

technical feat on the player’s part, this). Lindberg’s Jeux d’Anches

is a much more congenial piece, though still very demanding, but nevertheless

quite accessible. (Lindberg’s earlier Metal Works for

accordion and percussion is rather more difficult and taxing.) This

is the piece’s second recording (Rantanen recorded it on Finlandia FACD

404 some years ago) and this one is as fine as the earlier recording.

The most ambitious work here is Ratkje’s Gagaku

Variations for accordion and string quartet. It is a quite substantial,

if overlong piece evincing great imagination and sometimes great beauty,

alternating ruthlessly energetic variations and moments of deeply felt

tenderness. It cleverly eschews the all too evident trap of fake Orientalism

though the very end of the piece makes its origin quite clear. The accordion

does not stand out in a soloistic position but is rather a full-time

equal partner adding some further instrumental and expressive colour

to the strings’ sound. As in Hoskawa’s In der Tiefe der Zeit

for cello and accordion which I reviewed recently, the accordion suggests

the sound of the sho (i.e. the Japanese mouth-organ).

Haltli is a formidable player as well as an excellent

musician. He plays with strength, commitment and conviction and his

committed readings of these often difficult pieces cannot be bettered.

Now, this is a most unusual programme of works for a most unusual instrument;

and some may find it hard to listen to it in one take. This is obviously

the sort of thing to be sampled, piece by piece; and I would suggest

that any newcomer to this repertoire starts with Lindberg’s piece. Not

for the faint-hearted, maybe, but well worth the effort.

Hubert Culot