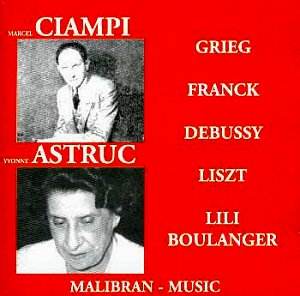

Itís appropriate that these two significant French

musiciansí names should be linked together because they married in 1920.

Of the two itís Ciampi who had the more internationally known career,

latterly having a raft of distinguished pupils Ė Loriod, Ousset and

three Menuhins (Hephzibah, Jeremy and Yaltah) amongst many. He was a

student of Diemer at the Paris Conservatoire and was one of the pianists

who was most linked with the venerable and leading French Quartet, the

Capet. Astruc is less well known, at least in the Anglo-Saxon world,

though she did make an early foray to Queenís Hall when Henry ("Henri"

in the notes) Wood brought her over. She was born in 1889 and was two

years younger than her husband. He died in 1980 but Iíve nowhere been

able to find her year of death. As a ranking player in the French school

she falls chronologically between Thibaud and Francescatti but as her

discs display hers was an entirely different temperament from the sensuous

elegance of the former or the scintillating brio of the latter.

If we know Astruc at all itís through her recording

of Milhaudís Concerto de printemps Ė a composer-conducted set from 1935.

And in fact her discography is small. She did record another major concerto;

the Bach in A, with an unnamed band conducted by Bret but itís hardly

received much currency in the intervening seventy years or so. Titbits

saw out the rest Ė the usual fiddle fancierís sweetmeats of Gluck, Kreisler,

Nardini and Novacek. Not much of a return but plenty of players of her

generation made no commercial recordings at all (where are the discs

of the Australian Alma Moodie or the peripatetic Englishwoman Orrea

Pernel who fought for the Delius Concerto and turned up at Prades, where,

admittedly, she was taped live?). Astruc discloses an equable, unruffled

but essentially small-scale personality in the Grieg Sonata. Ciampi

is inclined to be a little hard rhythmically from time to time (the

opening chord has unfortunately been chopped very slightly in the transfer)

and Astrucís precise but rather small tone, although very nicely equalized

in the best French string tradition, is not overburdened with opulent

projection. Her trills are quite slow as well. Her expressive and athletic

portamenti in the Romanza are enticing and even if Ciampi is inclined

to over-pedal, her quite slow vibrato isnít one that requires dramatic,

theatrical projection. She doesnít go in for evocative or lubricious

finger position changes, preferring a more discreet musicality, a cool

one, more Zimbalist than Seidel, and she abjures glistening emotiveness

at all times. Prim? Well, maybe. What I found more problematical was

a lack of tone colour in her playing Ė itís all a bit one-dimensional.

In the finale she again, of course, prefers direct lyricism to abandoned

romanticism and if thatís how you take your Grieg in C minor then you

will welcome her somewhat aloof refinement. It certainly makes a marked

change from bombastic blood and guts in this sonata.

Ciampi reappears in the slightly earlier recording

of the Franck Quintet in which he is on splendid form, technically and

expressively. This is one of the great performances of the work, eclipsing

in my view the Cortot/International Quartet recording and standing at

an entirely discrete stylistic remove from later traversals, even from

those securely in the French tradition (such as Descaves and the Bouillon

Quartet or that by the Chailley-Richez Quintet) or by, say, Schmitz

and the Roth Quartet from outside that immediate school. I daresay many

readers will not have heard the Capet and will suffer the experience

of Yehudi Menuhin who, when he first heard them in Paris, apparently

Ė so he says Ė ran screaming from the hall appalled by their senza vibrato

aesthetic. It is nevertheless enormously enriching to hear them Ė they

were at the furthermost point from the Lener Quartet at the time, I

suppose, one blanched white, the other saturated in warmth. The spectral

intimacies of the work have seldom sounded so full of despair, Capetís

venerable austerity so magnificent.

Itís good to hear Astruc and Nadia Boulanger in the

two pieces by Lili Boulanger. The Introduction is played with a rather

tenser vibrato than she revealed in the Grieg and in the Nocturne she

plays with freewheeling chastity. Malibran are proving to be truffle

hunters extraordinaire when it comes to now forgotten French musicians

of the inter-war years. Iíll do a deal with them; I wonít mention the

English translation in the booklet (oh dear) if they release the following;

Gabriel Bouillonís Pathé discs and Ė letís chance it anyway Ė

the fantastically rare 1906 Zonophones of Jules Boucherit, doyen of

French fiddlers. Gentlemen?

Jonathan Woolf