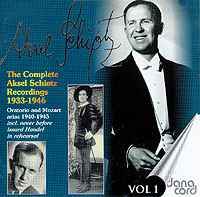

The first volume in Danacord’s set of ten devoted to

the art of Aksel Schiøtz and organised by Gerd, his widow, is

devoted mainly to oratorio and opera. Born in 1906 he studied modern

languages at University and gave his first solo song recital (he was

for many years a member of the Copenhagen Male Choir) aged thirty in

1936. His first recordings with his mentor Mogens Wöldike followed

soon after and this disc collates those made between 1940 and 1945,

the year before the tumour operation that ended his career as a tenor.

After 1948 he reappeared as a baritone and devoted himself to extensive

teaching.

His nearest Anglophone equivalent I suppose is Heddle

Nash. Schiøtz had a lyric tenor with a good top, depth at the

lower end of the range, stylistically pure and apt, conscious of performance

practice. He lacked the Englishman’s floated head voice and spinto minstrelsy

but possessed a stronger weight in the lower voice that gave him a splendidly

rounded compass. Indeed he challenges Nash on his own turf in the first

items from Messiah and acquits himself with real distinction. One would

never know that English is not his first language unless one listened

very closely to some minutely unidiomatic vowel sounds but his style

is supple and forward-looking with Wöldike lending lithe and flexible

support. In Comfort ye he sings pardoned in two, not the

three vowels beloved of English tenors. Wöldike’s harpsichordist

is an active presence in Ev’ry Valley and there are excellent

string emphases; he’s deeper in timbre than Nash’s lighter tenor, his

runs excellent. No one for me can touch Walter Widdop in these moments

but Schiøtz matches almost anyone else for beauty of tone and

incisive musicality. The Buxtehude is a ravishing performance; it has

style and simplicity of utterance, a sense of laced delicacy (note the

string players accompanying, members of the Koppel Quartet); the voice

itself is wonderfully well equalized - oddly indeed at some moments

it does take on a baritonal extension prefiguring the tragic calamity

of his brain cancer. In the aria from Bach’s Christmas Oratorio one

can perhaps feel Schiøtz push the voice, particularly in upward

extensions, and he doesn’t sound altogether free in voice production

(though this was a session mate of the Buxtehude and recorded at the

same time).

But the Matthew Passion aria with Morgens Steen Adreassen’s

delightful oboe has great reservoirs of depth and profundity and the

choir, which sounds small, is expertly drilled. The Dowland songs are

accompanied by Jytte Gorki Schmidt’s guitar and are in the elite category

as performances. They have an affecting freshness and modernity, despite

the guitar, and feature sovereign breath control, dynamic shading and

colouristic beauty. In Flow, my teares it is more than instructive

to hear the phrase Down, vain lights sung with such lucid and

incremental hardening of tone. His Mozart arias are imperishable reminders

of his artistry. Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön is most

beautifully phrased, with artless elegance and Dalla sua pace is

characterised with effortless skill – contour, dynamics, the depth and

exquisite control of the lower register – and his Il mio tesoro intanto

has more of his splendid runs and tremendous breath control. My

only disappointment was Un’aura amorosa, which sounds rushed.

Whilst his tone darkens nicely he can’t match Nash in idiomatic ease

here or in sheer vocal plangency. He has real style and a sense of projection

in Lensky’s aria from Eugene Onegin (in Danish) and his Haydn

is full of purity and, once more, stylistic acumen.

The disc is rounded out with a ten-minute rehearsal

segment of two Handel arias - Love sounds the alarm from Acis

and Galatea and Sacred raptures cheer my breast

from Solomon. These post-date by five years his earlier published

Handel from Messiah and here in 1945 the style is a little heavier –

but the former has eloquent runs far superior to the hit and miss latter.

These were with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra of Stockholm, which

may account for the heavier and more earthbound weight, less like Wöldike’s

more forward looking effect which is itself rather reminiscent of Boyd

Neel’s similarly fluent conducting.

The disc comes with texts and archive material – letters

from the singer and reminiscences of Wöldike and Schiøtz’s

comments on Messiah and Dowland. I hope I’ve conveyed something at least

of Schiøtz’s eloquent musicality; he was without question one

of the very greatest singers of his time and this series pays its own

powerfully eloquent homage to him, not least in Andrew Walter’s magnificent

transfers.

Jonathan Woolf

See also review

by Christopher Howell