'La Gioconda' is one of that group of Italian operas

which might be termed conviction opera, for want of a better phrase.

Concerned with the depiction of character and relationships via a series

of dramatic events, these works can sometimes degenerate into a series

of set pieces barely connected by a creaky plot. But when they are performed

with drama and conviction, then they are transformed. 'La Gioconda'

is just such a piece, dependent on a full-blooded diva in the title

role to carry the audience with her. So it is understandable that the

piece rarely receives performances outside Italy. The fact that it is

best known for the ballet music (the eponymous 'Dance of the Hours')

only renders credibility more difficult.

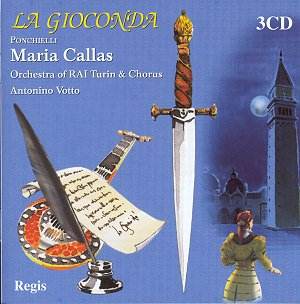

Callas recorded 'La Gioconda' for EMI in 1959 and it

was the role in which she made her Italian debut, at Verona in 1947.

But it was one of the heavier roles that she dropped and she rarely

(if ever) performed in the opera after 1953 (and in fact only gave 13

performances of it between 1947 and 1953). This is her first recording

of the opera and dates from 1952. It shares the same conductor (Antonino

Votto) as the EMI recording and has perhaps a marginally better cast

than the EMI recording. Callas had refined her interpretation by the

time of her second recording, she declared that anyone who wanted to

understand what she was about should listen to the final act. But everything

that she sang is of interest, and the earlier recording has the advantage

that fewer apologies need be made about the state of her voice.

The opera opens with the chorus, in poor form, singing

with more conviction than accuracy. But Paolo Silveri displays his fine,

shapely baritone as Barnaba. Callas's first entrance is quite discreet,

Ponchielli gives the performer no opportunity for spectacular dramatics

at this stage, though Callas's contributions later in the act are heartbreaking.

Votto controls the drama well so that the set pieces flow into one another

to create a dramatic ensemble. Key to all this is Silveri, his portrayal

of scheming, treacherous Barnaba.

As Enzo, Gianni Poggi's big scene opening Act 2 is

frankly a disappointment. A tenor with a big, open-throated technique,

his voice shows disappointing signs of an incipient beat. And his performance

is unimaginative and four-square. In ensemble, particularly with Callas,

he seems to be spurred on to better things, but alone he is a disappointment.

Fedora Barbieri's Laura displays a firm voice and fine array of low

notes, but often she seem unwilling, or unable to join the magnificent

notes into a decent line. As Laura she sounds rather too mature. Against

Callas's volatile Gioconda, Barbieri sounds positively matronly. But

they trade insults in a fine manner and their duet fairly crackles.

It is unfortunate, though, that they could not quite agree the pitch

of the final note.

Neri displays a wonderfully dark voice as the implacable

Alvise. His and Barbieri's scene in Act 3 is spine tingling stuff. But

in terms of vocal sound quality, this is much more Luna and Azucena

than Otello and Desdemona. This is partly Ponchielli's fault for the

tessitura of the role of Laura, but Barbieri seems too content to play

the role like many of the other disappointed, mature women in her repertoire.

But it is for the last Act that one listens to 'La

Gioconda' and the entire act belongs to the title role, here Callas

completely makes it her own. This is conviction opera indeed. What in

lesser hands could easily become maudlin is turned into real tragedy

and she takes the other singers with her, creating a wonderfully dramatic

ensemble. Callas plays the role with a voice that is often plummy and

veiled. She makes much use of her distinctive chest register with frequent

dramatic changes of gear. All this contributes to Callas's magnificent

portrayal of the volatile Gioconda, but it is not for the faint-hearted.

As a bonus, there are two tracks that Callas recorded

in 1949. A Casta Diva from 'Norma', recorded without chorus, is truly

a demonstration of how this artist could change her vocal quality depending

on the role. Though her interpretation may have deepened over the years,

this is a beautifully sung performance.

The other bonus track is the Liebestod from 'Tristan

und Isolde'. Callas sang a surprising amount of Wagner - 12 performances

of 'Tristan und Isolde' between 1947 and 1950, 6 performances of 'Die

Walküre' in 1949, 4 performances of 'Parsifal' in 1949. In fact

she was singing Brünnhilde when Serafin asked her to stand in for

an indisposed singer and sing Elvira. Which she did, the following day,

to great acclaim. And the rest, as they say, is history. But there can

be few singers that can have made such a remarkable transition, so it

is fascinating to hear the young Callas performing Wagner. Sung with

a wonderful sense of line and a feeling for the fioriture, surprisingly

few of the Italian words come through.

No mention is made on the discs about how the transfers

were made. I could almost have imagined that they were done using something

like the method used by Nimbus with a natural resonance being added

at the time of playback. However the transfer was effected, it was done

with minimum interference. The sound is adequate and natural sounding

with a wide dynamic range though it can become rather congested in the

big ensemble numbers. This recording has also been issued on the Fonit

Cetra label, in a transfer which was well received, but without the

fascinating two bonus tracks.

Though this will never be a library recording, this

record is a must for all lovers of Callas and those interested in the

recorded history of 'La Gioconda'.

Robert Hugill