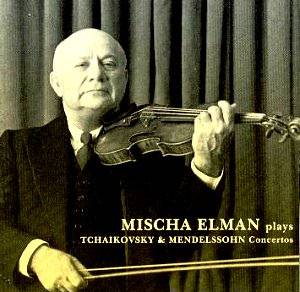

Elman made two commercial recordings of the Tchaikovsky

Concerto. The first, with Barbirolli in 1929, has seldom been out of

the catalogue in one form or another. The second dates from an LPO session

with Boult in 1954 and is much less well known. But dating from December

1945 comes this live Boston/Paray traversal that catches the great violinist

still on the right side of physical infirmity and a gradual but inexorable

waning of powers. These latter do manifest themselves in particular

ways in the companion concerto, the Mendelssohn.

In terms of structure the Boston performance of the

Tchaikovsky differs little from the 1929 traversal; the timings for

the first movement are in fact almost identical though there are differences

in matters of thematic emphasis, metrical displacements, vibrato usage

and phrasal elasticity. This is still however, very recognisably, the

master tonalist of old, one who imbued every phrase with lavish intensity

and a throbbing, molten vivacity. He brings intense concentration and

expressive shading to his opening rhetorical statement and the Elmanesque

rubato that no-one could quite match. He is very slow and highly romanticised;

the orchestral pizzicati that point the rhythm are delayed an age as

a result. Elman lavishes prayerful simplicity after the cadenza and

his voluptuous vibrato takes on an ever more devastating candour. Behind

him the Boston winds are highly characterful and though there is some

crunch and other such aural damage (especially in tuttis) it will detain

only the pickiest of listener. Elman is not quite certain in his passagework

at the end of the movement – though the harmonics are negotiated well

enough – but one can hear how eventful and tactful is Tchaikovsky’s

orchestration when a fine conductor is in charge clarifying lines. The

orchestra emerge newly distinctive in the slow movement – flute and

clarinet principals especially. Elman’s phrasing rises and falls, ever

more rapturous and involved, his line taking on more and more a sense

of direction, the orchestral string blending under Paray of real distinction.

In the finale the orchestral accents are commensurately strong; this

is the one movement where the excitement of a live performance impels

Elman to a fleeter performance than his earlier commercial recording

though oddly it’s not necessarily more overpoweringly exciting.

The Tchaikovsky is a reminder of Elman’s eminence;

in the first decade of the century it was he who was the most fêted

of young fiddlers and the Tchaikovsky was for a decade or more "his"

concerto. The Mendelssohn dates from November 1953. His slightly earlier

commercial recording with Defauw and the Chicago Symphony has always

been highly regarded whilst the twilight Vanguard session in Vienna

that produced the later disc, with the State Opera Orchestra under Golschmann

has not. Again Elman’s overall conception changed little and the difference

in timings between Mitropoulos and Golschmann are negligible. Elman

is perhaps guilty of some rough playing in the opening movement of the

Concerto; some rather inelegant expressive pointing is another particular

feature (but how irrepressibly Elman it sounds). With the highlighting

comes a rather static introspection and an equally glutinous tonal projection

that can too dramatically personalise the line. Nevertheless against

this one can cite the finger position changes that remind one of the

old lion and the beautiful strands of lyrical weight he can and does

lavish – even if the vibrato itself is now slowing and the tempos ossifying

somewhat in terms of phrasal interconnectedness. In the Andante he no

longer possesses the elfin projection or sense of relaxation that the

greatest interpreters of this work bring to it (if indeed he ever really

did – his recording with Defauw, though of course highly personalised,

was highly impressive). He does rather distend the movement (to 7.50).

He is jaunty and unmotoric in the finale; he never used it as a piece

of showmanship as other, less scrupulous colleagues did. He also makes

a couple of fluffs on the lower strings but these are minor details

– even if the final bars are rather grandiosely emphatic.

The recordings have been handled with skill; the attendant

problems are really insignificant ones and won’t be in any way problematic.

As one who welcomes anything by Elman, no matter how minor, these major

live performances have a still compelling part to play in expanding

and widening the Elman discography; that they are ancillary to the main

body of his recordings is undeniable but wise heads will want to hear

them and reflect on Elman’s place in the hierarchy of great violinists.

Jonathan Woolf