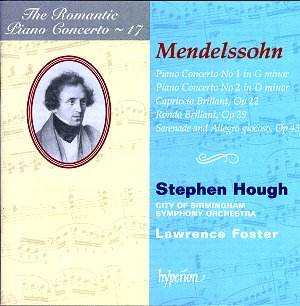

Judging by the impressive quality of Houghís playing

here Mendelssohn was no mean player either. Framed by three ten to twelve

minute light-hearted single movement works, the two concertos (already

more familiar to music lovers than the bulk of Hyperionís Romantic Piano

Series because they sustain a fairly regular position in the repertoire)

are always a pleasure to listen to. Mendelssohnís short life, cut short

in 1847 as concert life and the technical developments of the piano

and the techniques of its performers were beginning to hot up, thanks

largely to Liszt, precluded a role for him. He certainly disapproved

of Lisztís performing antics, not for Mendelssohn the paraphrase of

opera tunes of other composers though he himself was a fabulous improviser,

but he remained part of the circle (including the Schumanns and Chopin)

of innovative executants as well as composers. In this latter capacity

he was not driven to ground-breaking when it came to matters of style,

for one can find plenty of signs of Mozart, Beethoven and Weber in his

writing as well as absorbing the influences by his contemporaries. The

relationship between piano and orchestra is a case in point; as with

Chopinís two concertos, the solo instrument hardly rests while the orchestraís

contribution is of relatively little import. Nevertheless the music

of these works, all written in the 1830s, is always both charming and

delightful. The finale of the first concerto remains a particular favourite

with this reviewer, vibrantly thrilling once past the slightly portentous

orchestral opening. There is an almost operetta flavour to its main

melody, essentially a galop from the music of the salon, and none the

worse for that. That Liszt sight-read it flawlessly from Mendelssohnís

manuscript in front of the composer in Erardís Paris showrooms made

an indelible impression on the composer, despite his opinion of the

showman pianist.

Mendelssohn would surely have approved of the performances

here; Houghís playing provides a broad palette of colour, plenty of

sparkle, lyrical warmth of tone and a sense of ease in the clarity of

the passage work. But we all know itís far from easy. Lawrence Foster

and the CBSO make the most of the infrequent opportunities to shine

in the orchestral ritornelli and accompany with stylish sensitivity.

Christopher Fifield