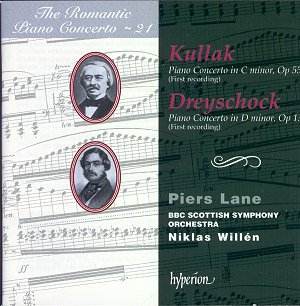

This is really going down the byways with two composers

whose names are barely known, if at all. Kullak’s reputation rests largely

as a teacher of, among others, Scharwenka, Moszkowski, Nikolai Rubinstein,

Kwast and Reubke, all fine players themselves. Born in Poland he studied

in Vienna under Czerny, Nicolai and theoretical studies with Simon Sechter,

an eminent trio of masters in their fields. His career path tended to

be as a teacher of the aristocracy, no bad move from his bank manager’s

perspective, and he also founded a music association and music schools

in Berlin. His concerto was composed in Leipzig about 1850 and is a

jolly affair with many engaging tunes recalling either arias from a

Bellini opera or an Offenbach operetta, though of course the predominant

influence is that of Chopin with a splash of Weber here and there. The

technical challenges sound awesome in the bravura passages of double

octaves, cascading thirds, and plenty of scales and arpeggios.

Born in the same year as Kullak, Dreyschock was from

Bohemia and, according to the former, was an even better pianist than

Liszt, which was an accolade worth having. In the 1840s he seemed to

be everywhere on tour in Europe, giving sensational performances wherever

he went, amazing everyone including Cramer who told him he had no left

hand but two right hands and Berlioz who praised his fresh, brilliant

and energetic talent. Dreyschock’s teacher Tomasek made some rash prophecy

that someone one day would be able to play the left-hand of Chopin’s

‘Revolutionary’ Study in octaves instead of single notes. His pupil’s

response was to practise twelve hours a day for six weeks (504 hours)

and become that pioneering pianist far earlier than his teacher had

expected. Mendelssohn was astonished, Liszt rushed home to practise

and managed to sustain his position on top of the pile as a result,

while Hans von Bülow surrendered ungraciously with the words ‘a

got-up furore, an homme-machine, the personification of a lack of genius’.

Until the finale it is not so frothy as the Kullak concerto, yet the

earlier movements have a certain degree of depth to it. Initially comes

up to expectation in terms of establishing a dramatic mood befitting

a minor mode (surprisingly Kullak’s is also but after the opening dramas

of C minor recalling those in the same key by Mozart and Beethoven,

you would not think so as it bubbles along). There’s Mendelssohn aplenty

in Dreyschock and some lovely moments for piano with solo cello.

Piers Lane plays both of them superbly. He is an exceptionally

fine pianist and has proved himself utterly at home in this Hyperion

series with three other discs already to his name. The BBCSSO are old

hands at it too, Niklas Willén their conductor here is not a

familiar name to this reviewer, nor does he get a biography in the booklet

but nonetheless makes a creditable contribution to the proceedings.

If you’re feeling low, just put on the Kullak concerto and you’ll be

smiling in no time.

Christopher Fifield

The

Hyperion Romantic Piano Concerto Series