We all come to particular composers in different ways.

I became fascinated by Mahlerís music even before I had heard a note

of it. Though starting to discover classical music in my teens I had

not yet come across Mahler when I was taken by an entry in a book on

early twentieth century history. "Mahlerís vast symphonies sewed

the seeds for the destruction of Austro-German Romanticism that would

mature in the works of Schoenberg." I suppose it was the suggestion

that one man could apparently have such a decisive influence on the

history of ideas that so fired my imagination at the time and made me

want to investigate further. How true that bald statement is could provide

many hours for discussion, but I think that as a short synopsis of one

very important aspect of Mahlerís art itís a useful beginning. With

the benefit of hindsight I can see that what I was reading about was

the crucially important matter of Mahler standing between two worlds

of thought as expressed in two different strands of musical history.

There was Mahler at the end of one tradition and at the start of another;

in the right place at the right time in one of those rare periods where

itís possible to see and hear change take place over a short time. All

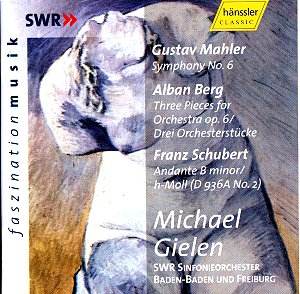

of this is germane to this review because you will see that Mahlerís

Sixth is not the only work contained in this set. The works by Schubert

and Berg are there as the result of a decision by conductor and company

to set Mahler in his historical context. So here is Schubert from before

Mahler; and Berg from after him; the First and Second Viennese Schools

with Mahler in the middle.

Bergís Three Pieces almost choose themselves for this

purpose. Listen to passages in the Scherzo of the Mahler symphony where

the lower brass and woodwind explore the basement of his orchestraís

sound palette to hear where Berg was coming from; likewise the nightmarish

introductory passage of the fourth movement. Berg also distorts dance

rhythms in his second piece (Round Dance) a device that Mahler spent

his life using to great effect. Then there are the hammer blows. Both

Mahler and Berg incorporate hammer blows into their last movements as

devices to signify negation, the progress of symphonic determinism cruelly

cut off in its prime. The Schubert link to Mahler is perhaps less easy

to hear but it is certainly there. Like Schubert, Mahler was a composer

of songs who then turned his symphonies into extended vehicles for song-like

material, especially to evoke nostalgia. The Andante movement realised

from Schubertís unfinished Tenth Symphony has, as David Hurwitz points

out in his notes, a special nostalgic charge in the way major and minor

keys are strangely juxtaposed to suggest ancestry to the Andante in

Mahler's Sixth. Gielen gives a delicate and rarefied performance of

this rescued fragment with some excellent woodwind solos from the orchestra

and an air of mystery too.

Under Gielen, Bergís tragic and haunted sound world

is given a performance of power and detail. The sustained melodic line

in the first piece (Präludium) is pitted against an especially

well reproduced bass end with lower brass leaving marks in the mind

like giant footprints in the sand. Iíve already referred to the second

piece (Round Dance) but note that though Gielen is very aware of the

shifting perspectives, the nightmare phantasmagoria, there is still

an underlying iron grasp on the material borne of intimate knowledge

that means the piece never becomes so disjointed you cannot follow.

The final piece (March) carries the tragic core and climax of the work

and the urgent pressing forward that Gielen employs allows the music

to seethe and boil with terrific, pent-up force that only finds partial

release with the hammers. Notice too the extraordinary bronchial-like

wheezing of the muted horns, a sound Mahler knew very well, but which

here is carried into a new dimension altogether. Example of the excellent

balanced recording quality right through.

Most peopleís reason for buying this set will be the

Mahler symphony and it is to that I now turn. With Gielenís perceived

credentials as an interpreter with head and heart set in the twentieth

century I have to say I was mildly surprised by some parts of his performance,

as it isnít quite what I expected. There are certainly more examples

of what one might describe as personal involvement here than there are

in previous symphony recordings of Mahler that I have heard from him

- the Second (Hänssler Classic CD 93.001) and the Third (Hänssler

Classic CD 93.017) that I have reviewed here. In the first movementís

the second subject, a portrait of Mahlerís wife, is buoyed along with

all the schwungvoll that Mahler could ask for but also by some

unashamed rubato that certainly raised an eyebrow from this reviewer.

However never let it be said I should base a review on what a performance

is not rather than what it is. What you get overall in the first movement

is a concentrated blend of very grim determination laced with yearning

nostalgia. Gielenís overall tempo choice is slower than many colleagues,

nearer to Barbirolli than Scherchen at the two extremes, which certainly

gives him chance to make sure everything is heard very clearly but it

does lack something in energy. The exposition is full of incident, however,

and more than justifies the repeat. Along with the very moulded Alma

theme notice too the plangent high woodwinds and the very low brass.

This exploration by Gielen and his engineers of every register of the

orchestra will be a mark of the recording right the way through and

is certainly one of its plusses. Not least in the pastoral/mountain

interlude where the cowbells are perfectly placed to add a cold, unforgiving

air against the shimmer of the strings. The whole effect of Gielenís

delivery of the recapitulation is then an emphatic statement that life

goes on in spite of everything and that clear impression carries into

a quite hedonistic treatment of the coda. Not one that has any hint

that there is tragedy bearing down on us. Alma Mahler remarked that

when he wrote the Sixth Mahler was "in full leaf and flower",

which is exactly the impression gained here from Gielen. True, there

are demons, forces working against our hero, but he is on top of them

at first and there really is nothing to knock him off course. Here is

a fully thought out performance by a conductor who understands only

too well the implications of this movement.

As should be obvious from the Berg, Gielen is good

at "ugly" and the Scherzo, correctly placed second, shows

this again. The overall tone of the movement, its general gait and delivery,

is as real counterpart to the first movement so what we hear is again

very grim and nostalgic at turns. The main scherzo material echoes the

first movement march and then the mood is lightened by the altvärterisch

trio sections that Gielen delivers with a halting, awkward quality that

is never grotesquely twisted out of shape as it can be and is under

Tennstedt and Levine. Indeed much of the effect of these passages is

achieved by a nice contrast in tempo between the interludes and the

main material. The tension doesnít really flag and the movement hangs

together well mainly because again the detail in the score is attended

to well, but itís a close run thing for all that. Anything slower than

this and there may have been a problem. As expected, those twentieth

century sounds, those Bergian "pre-echoes", are attended to

by Gielen, as also is the sinister descent at the close. Unlike the

close of the first movement, there is the feeling under Gielen that

the skies are darkening at last.

The Andante is then given a rhapsodic, free-spirited

performance that Gielen clearly sees as his last chance to show us our

hero in happy times before the great struggle that will ensue in the

last movement. In this Gielen tells us he is supremely aware of the

true nature of tragedy. That only by showing us what the hero is losing

do we appreciate his loss when it finally comes and placing the Andante

third has always seemed to me to be fully in line with that. When the

last movement immediately follows the restful dying away of the third

Gielen then manages to deliver such a devastating impression of "as

I was sayingÖ" that he fully justifies this particular inner movement

order rather than the lesser played one of Andante second and Scherzo

third. Note in the opening pages, surely the most remarkable Mahler

ever composed, the almost chamber-like filtering of textures with lower

brass and percussion again impressing with the sense of looking ahead.

Gielen then attends to every mood and facet of this movement. Unlike

some he doesnít stress the tragic at the expense of the few passages

of light that depict what is being taken away by fate as represented

by the hammer and so achieves just the right balance for the drama.

In fact it is a summation of all we have heard and felt in the previous

three movements. The two hammer blows are clear and definite. Though

they still sound like a very large bass drum being struck they have

the right impact to depict negation. In keeping with the score edition

he is using, Gielen rightly respects Mahlerís wishes and doesnít restore

the third blow. In fact so well does he present the passage where once

there was a third blow that this is one of those performances where

I am certain a third would have been excessive, as Mahler concluded.

Is this fate playing a cruel trick on us, we ask? Just when we are expecting

it to batter us for the last time, it doesnít. By now the damage is

done and the final, shattering verdict is saved for the very end.

You will gather that I rate this performance highly.

It is as if Gielen feels freer in this work than he usually does in

Mahler to involve himself more, to be a little freer with his interpretation,

more emotional. Hence the slightly larger-than-life Alma passages in

the first movement and the fiercer emotional contrasts inside the Scherzo

and between the ugly Scherzo and the beauteous Andante. The last movement

also has profound contrasts on display but I just wish there could have

been that little more sense of urgency here, a little more "do

or die" in the passages where Mahler finds himself propelled towards

the abyss. This would have turned an excellent performance into a great

one.

Clear and uncluttered studio sound with every detail

clear can be heard in all three works in the set. There are also detailed

notes by David Hurwitz whose essay on the Mahler can be read by those

who know the work well as well as serve as an excellent introduction

for those who may never have heard it before. The orchestra responds

to Gielenís every demand too. They donít have the heft and power of

New York, Amsterdam, Vienna or London with the brass especially stretched

though always accurate and perhaps that produces a tension of its own.

This is a Mahler Sixth to go into the collection of all those who recognise

this symphony as one of the profoundest statements on the human condition

in music. Where man meets fate and the nineteenth century meets the

twentieth. I still maintain my admiration for Thomas Sanderling (RS

953-0186), Mitropoulos (contained in the NYPO Broadcasts boxed set),

Rattle (EMI 7 54047 2) and Zander (IMP DMCD 93), but I will return to

Gielen often.

A well-executed and very absorbing Mahler Sixth placed

in fascinating musical context by Schubert and Berg, all well-recorded

and played

Tony Duggan