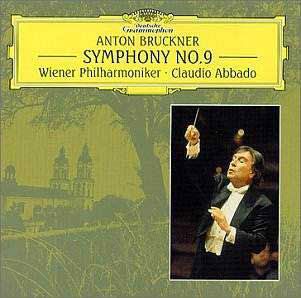

Claudio Abaddo has taken his time with his Bruckner

recordings and there is still no sign as to whether he has embarked

on a complete symphony cycle or not. So far DG has released the First,

the Fourth and the Fifth, but a look at the date of this Ninth shows

that it remained in the DG archives for over four years before release.

I wonder why. It canít be because of inferior quality. Opinions and

preferences aside, interpretation and playing are both excellent and

whilst some may find the sound rather closely blended it is still a

rich and refined recording with lots of detail.

First praise must got to the Vienna Philharmonic. Always

special in this composerís music, particularly with a conductor they

like and admire, the brass is powerful and unflagging right the way

through this "live" recording, but they also maintain that

rich, sonorous sound that never tires the ear and can vary tone in the

blinking of an eye. The strings also have the saturation sound these

players specialise in and with Abbadoís stress on the lyrical aspects

of this score maybe at the expense of its architectural that counts

for a lot. Perhaps the woodwinds suffer just a little in the recording

balance but they more than match their colleagues.

As I indicated, Abaddo is, as ever, the lyrical Brucknerian.

This leads him to always make sure that the great outbursts of often

anguished brass in the first movement never sound coarse. This avoidance

of the coarse can diminish somewhat those architectural properties that

are so much a keynote of Brucknerís method. By that I mean that at those

times when Brucknerís geography calls for a sudden mountain range to

be marked very vividly on the musical map Abaddoís instinct is to smooth

over the transition slightly and this is helped by the closer recording.

More air around the instruments would allow the silences to be filled

in by the cathedral reverberation that is always in Brucknerís aural

imagination too. As I say all this accentuates for me the impression

that lyricism rather than architecture is on Abbadoís mind. But no matter,

itís a valid view that Abaddo projects with confidence and conviction

and Iím prepared to go along with it even if I donít find it entirely

convincing myself. In the third movement Abbado therefore shapes the

great themes with a particular warmth and sincerity, more human, less

spiritual, and here he is at his best, his interpretation most appropriate.

Which is not quite what I felt in the first movementís corresponding

sections which need more black mystery, more ghosts in the machine.

For that you want Furtwänglerís 1944 concert recording (Music and

Arts CD730) made in Berlin as that city prepared to burn. However, I

wouldnít want you left with the impression that this is a Bruckner Ninth

without power and heft. There is plenty of that, especially in a powerful

and evil pounding scherzo where the VPO brass shake off their golden

chain mail to replace it with a suit of armour that the Black Prince

himself would have worn with pride.

For many years my own reference version of the Ninth

has mostly been with Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic on DG Galleria

recorded in 1966 (429 904-2). Karajanís remake from eight years later

is very nearly its equal but I still prefer the more spacious recording

and sense of the numinous of the earlier version, so make sure to order

the number I have given for the 1966 version. Karajan also dares to

make those huge dynamic contrasts that Brucknerís score abounds with

really tell and which Abaddo doesnít seem to want to press too far.

Karajan is also backed by an orchestra whose range of expression in

every part of this score is huge containing powerful, thrilling brass

and string playing that rises to heights of eloquence never equalled

in this work. However, compared with the Vienna Philharmonic for Abbado

you do have the impression that the Berliners of 1966 have been given

their heads to an extent that the slightly more reined-back Viennese

are not and there is enough air in the acoustic for them to really stand

out. Listen to the black trombones, the ringing trumpets, the achingly

beautiful cellos and, above all, Karajanís sense of the dramatic matched

with his flair for heavenly calm. Apart from Karajan I have also always

admired Bruno Walterís nobler and softer-grained reading on Sony (SMK64483)

which is perhaps a better example of the kind of performance

Abaddo seems to be aiming for.

This is an interesting and rewarding Bruckner Ninth.

Not one to replace other top recommendations, but certainly one to take

down for a distinctive view.

Tony Duggan

![]() See

what else is on offer

See

what else is on offer