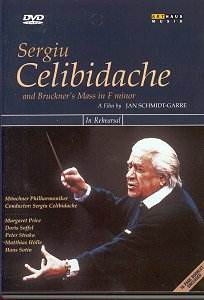

This is by no means the first documentary to be made

of Sergiu Celibidache, although this is the first release of this particular

film of the rehearsals and part-performance of Bruckner’s F minor Mass

made during an intensive two week period in late 1993. Jan Schmidt-Garre

had, before these sessions, spent four years filming Celibidache in

Germany, France, Rumania and Israel and the results of that film (available

on a Telarc video coupled with Dvorak’s Ninth Symphony VHS 4509-96438-3)

are perhaps more revealing of a conductor who famously eschewed recordings

than this single work documentary. His reaction to that first request,

"It’s of no interest to me whatsoever", is entirely characteristic

of the man and yet both that film and this one are imbued with an intensity

quite different from, say, the documentaries of other conductors, such

as Herbert von Karajan (one of which has also just been released on

Arthaus), which have an air of superficiality, even inevitability, about

them.

For one so averse to the recording process in any format

Celi is remarkably well served on film. There are astonishing performances

of Bruckner’s Sixth, Seventh and Eighth Symphonies (all once available

on Sony video) and an incredible coupling of Brahms’ two piano concertos

with Daniel Barenboim as soloist which, were they ever issued on commercial

CD, would go to the very top of my list of recommendations for those

works. Crying out for reissue is Celi’s Berlin Philharmonic recording

of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony, made 38 years after he last conducted

the orchestra. This only ever had a very limited circulation, but remains

an extraordinary document, and also includes rehearsal footage. There

is still some unpublished material – of Debussy, Dvorak, Mussorgsky

and Ravel (the Piano Concerto in G with Michelangeli and the LSO) as

well as the seemingly always available and famous film of Celi conducting

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture in the ruins of the alte Philharmonie (an

incandescent reading, albeit a simulated one).

This particular release, however, illustrates one of

the reasons Celi remained a problem for orchestras and management alike:

his excessive demands for rehearsal time. Others were (are), of course,

demanding – Gunther Wand and Jascha Horenstein, for example – but Celi

was exceptional in his demands for rehearsal time. There are times when

the soloists in this film look weary beyond belief (Margaret Price particularly)

yet the dividends from fourteen days of rehearsal and performance are

there to see and hear. This is intense music making, with a care for

dynamics only such prolonged preparation can yield. Rehearsing without

a score, Celi picks up on the smallest orchestral detail – a rising

sixth in the strings, for example – and his care over the details of

the human voice suggests a conductor who would have been miraculous

in opera (although, I suspect, one who would have been detested by singers,

much as Sinopoli was by some).

He effortlessly moves between German and English (he

was an exceptional linguist, speaking fluently some fifteen languages)

and injects his instructions to orchestra and choir alike with pepperings

of humour, and a little philosophy. There are still hints of the firebrand

who cowed orchestras in the 1950s and 1960s but generally the temperament

has mellowed. His appearance is now avuncular, rather than dashing and

volatile as he was in the Egmont excerpts, although he is still a captivating,

magnetic presence. And his request for a break in the rehearsal – "for

twelve minutes" – is pure magic. Why so specific a time?

The disappointment must be that there is no performance

of the whole work to accompany the revelation of the rehearsals. At

60 minutes it is very short measure for a DVD and as such will be of

interest only to people who have a fascination with the art of music

making – or Celibidache himself. I hope, however, that his Bruckner

symphonies will appear on DVD soon – they are exceptional by any standards.

Marc Bridle