|

|

Search MusicWeb Here |

|

|

||

|

Founder:

Len Mullenger (1942-2025) Editor

in Chief:John Quinn

|

|

|

Search MusicWeb Here |

|

|

||

|

Founder:

Len Mullenger (1942-2025) Editor

in Chief:John Quinn

|

|

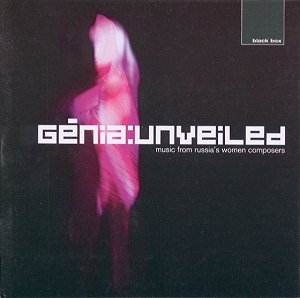

GÉNIA: UNVEILED Music from Russia’s Women Composers Elena FIRSOVA (b. 1950) Elegy (1979) Hymn to Spring (1993) Sofia GUBAIDULINA (b. 1931) Chaconne (1962) Sonata (1965) Lena LANGER (b. 1975) Reflection (1993/98) Galina USTVOLSKAYA (b. 1919) Sonata No. 2 (1949) Sonata No. 6 (1988) Recorded at Gateway Studio, December 1999 and March 2000 |

| CD available for post-free online mail-order or you may download individual tracks. For some labels you can download the entire CD with a single click and make HUGE savings. The price you see is the price you pay! The full booklet notes are available on-line. |  |

|

NOTE • Click on the button and you can buy the disc or read the booklet details • You can also access each track which you may then sample or down load. • Further Information. |

|

|

The front cover of this CD bears only the first two lines of the above heading – the main title in a particularly unbeguiling typeface which you can’t be bothered to read – plus the name of the record company. Turn the disc over and you have a list of works, composers and timings. Nowhere is it suggested that Génia is a person, nor that she plays the piano, so if you don’t already know this, which I didn’t, you have no real idea what you’re looking at. I suppose a lot of money has been spent on market research, but I can’t help thinking that this kind of presentation, of which we see more and more, can only discourage a prospective purchaser who picks up the disc while browsing.

The inside pages of the booklet are printed in white on different shades of pink. Very occasionally the pink is so close to white that you have to squat by an open window wearing expensive glasses to be able to read what is written. On one of the easier pages to read we learn that Génia was born in the Ukraine in 1972 and has pursued a career as a pianist in the USA and in Europe, including playing with the Park Lane Group in London. She writes the booklet notes, which are slight and short on hard facts; inevitably she sees the works from the interpreter’s point of view, which should be interesting, but the text is peppered with quite a few "I thinks".

The two pieces by Elena Firsova are both extremely introspective and inhabit similar sound worlds in spite of their very different approach to piano writing. Elegy is a quiet, questing piece more or less without melodic content; for much of the time the music consists of single notes from different parts of the keyboard, added to a sound texture relying on liberal use of the sustaining pedal. The listener is sometimes put in mind of Debussy, but the musical language, freely atonal, is very much of its period and could easily be confused with any number of composers active in the sixties and seventies. The overall effect is striking and yet fragile; intriguing, compelling, yet curiously lacking any real emotional basis – you don’t know what the composer is wanting you to feel, in spite of her statement, quoted in the booklet, that the piece is "one of my most personal and intimate works." Hymn to Spring is composed of two musical elements, a series of simple chords giving the feeling of a solemn procession, juxtaposed with extremely rapid figuration, usually toward the top of the piano, which seems to suggest birdsong. Both works rise to a climax in the same way, with thunderous chords right at the bottom end of the instrument held on by the sustaining pedal. Both works end in a similar way, too, very quietly at the very top of the instrument. And the final similarity is the apparent coldness, music in which the human spirit seems to be largely absent.

For more than four minutes out of the six which make up Lena Langer’s Reflection the music is almost totally static, isolated notes pianissimo throughout the piano’s register creating an atmosphere more powerful than a simple description can communicate. A short passage rather like a Bach Two-Part Invention leads to a sudden eruption which culminates – oh dear, it’s becoming a cliché – in powerful, sustained clusters at the bottom of the instrument. "Bach" reappears before the music returns to almost-emptiness before subsiding into silence. The composer was only eighteen when the piece was first composed, and if the form seems to have been decided in advance rather than growing organically out of the material this is perhaps a sign of youth and inexperience. This is a striking piece nonetheless.

According to Génia, Galina Ustvolskaya rarely uses bar-lines yet "the music is propelled by a strong rhythmic drive". I don’t think I should have described her Sonata No. 2 in those terms. There are two movements, the second considerably longer than the first, and both are characterised by a slow quaver or fast crotchet movement with little or no rhythmic or melodic contrast. The music seems closed in and claustrophobic, even numb, which might just fit in with Génia’s assertion that it is music of "human sorrow". Yet she also speaks of a cry becoming a scream and being "forcibly reduced to a whisper. It is music that deplores the silencing of the dissenting voice." I don’t hear any of this myself. There is certainly a perceptible increase both in volume and intensity of dissonance, followed later by a corresponding reduction. The regular movement suddenly slows shortly before the end, which brings relief and is undoubtedly dramatic. The final diminuendo to nothing is also very affecting – and brilliantly executed by the player – but there rests the suspicion, firstly, that the musical material is stretched to the limit, and secondly, in common with Langer’s piece, that the idea of the work was its starting point and is more important than the notes of which it is made. The notes themselves are strung together in such a way as to offer not one glimmer of anything resembling hope or optimism, a characteristic common to her Sixth Sonata too. The piece runs for almost eight minutes, of which the first six or so are totally taken up with relentless, fortissimo dissonances interspersed with short periods of single-line chromatic melody. One marvels at the sheer courage of the composer in writing this music, exhausting as it must be for the player, and demanding an awful lot of the listener, if only in terms of patience. One tiny passage of gentler sounds gives way very quickly to a return of the opening music, which is how the sonata ends. Génia refers to the gentler passage as "a chorale" which "appears as a sign of hope", but if this is hope it is timid and short-lived indeed.

If both of Ustvolskaya’s pieces are characterised by a singleness of purpose they demonstrate also a singleness of method, a tendency to rely on one idea or device which many will find limiting. It’s a relief, then, to turn to the two works by Sofia Gubaidulina, both of which seem positively profligate by comparison. My heart sank at the massive opening chords of her 1962 Chaconne – more of the same, I thought – but I should have had more confidence. The music moves through a bewildering range of themes, textures and even styles. Suggestions of jazz jostle with the ghost of Bach and traditional music. And whilst you still might not choose this for a quiet evening’s listening in front of the fire, the very variety of emotion contained in it seems to allow for the existence of hope. Many of the same comments might be made of her Sonata of three years later, which follows an almost conventional three-movement form. The additional element here is a considerable number of sounds produced from inside the piano, and it’s a tribute to the composer that most of them seem integral to the musical argument rather than pasted on for reasons of effect. The second, slow movement, seems to suspend time, and the final movement provides a real virtuoso finish. As with Chaconne there are many passages of intense beauty which strike the listener even at a first hearing.

Génia is the perfect advocate for these works. She has all the virtuosity and stamina required. She seems to believe in the music and communicates her own conviction to the listener, which makes the trendy, discouraging presentation all the more puzzling and regrettable. The recorded sound is excellent. The programme is extremely challenging to the listener – not a lot of fun, but compelling and satisfying. The sheer, relentless grimness of Ustvolskaya’s two pieces here is too much for me, though, and I rather think I shall come back most often to the two by Gubaidulina. William Hedley |

E. FIRSOVA G. USTVOLSKAYA E. LANGER E. FIRSOVA S. GUBAIDULINA Get a free QuickTime download here |

|

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION •

You can sample only 30 seconds (or 15% if that is longer) of a given track. Select from the View tracks list. Each sample will normally start from the beginning but you can drag the slider to any position before pressing play. • PLEASE NOTE: If you are behind a firewall and the sound is prematurely terminated you may need to register Ludwig as a trusted source with your firewall software.

•You will need Quicktime to hear sound samples. Get a free Quicktime download here • If you cannot see the "Sample All Tracks" button you need to download Flash from here.

|

|

|

Return to Index |