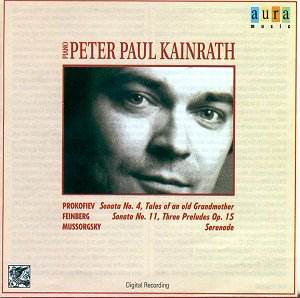

Most of the Aura discs I have reviewed recently have

been of historical material. This one, published in 1999, releases a

1994 session made in Ortisei over three days by the Italian pianist

Peter Paul Kainrath, then thirty. A student at the Bolzano Conservatory

he subsequently lived in Moscow for three years studying with Merzhanov,

successor to Samuel Feinberg, himself the focus of interest in this

rewarding disc.

Feinberg, 1890-1962 (the dates are wrong on the Aura

outer casing, but correct in the notes) was pianist, teacher, composer

and writer. Most famous, perhaps, for his Bach – the Well-Tempered Clavier

– and Beethoven he was an active proponent of the contemporary Soviet

literature, notably Scriabin of whom he remained an outstanding advocate

and Prokofiev. Popular in Germany he made an early series of 78s there,

as well as sessions in Moscow – now collected on Arbiter – which succeeded

in defining his aesthetic for the remainder of his life; Chorale Preludes

and Feinberg-transcribed Bach, the Appassionata, Liadov, Scriabin and

Stanchinsky’s Prelude in canon form. His Well-Tempered Clavier is well

enough known and has been intermittently available over the years but

the last recordings, made when he knew he was dying of cancer, possess

a transcendent depth that makes them amongst the most luminous of all

such recordings of the Bach Chorale Preludes. The occasionally rather

brash attack of the younger man had been replaced by a simplicity and

directness that admitted no externalised posturing.

So this disc is a well-chosen exploration of Feinberg

as transcriber, composer and executant virtuoso and opens with the transcription

of the Mussorgsky. Feinberg retains the saturnine, almost hypnotic concentration

of the original song and Kainrath gives it the weight and space to sound.

Feinberg’s Three Preludes were published in 1925. The first, abrupt,

striving, constantly searching for the plateau of legato simplicity

is constantly thwarted whilst the second is more obviously reminiscent

of Scriabin with its moments of stasis and reflection, withdrawal of

tone and the characteristic Feinberg admixture of quasi-Bachian paraphrasing.

The final Prelude is urgent and virtuosic, with an inward looking central

panel that gathers itself for a dynamic and conclusive ending. The Sonata,

a single movement, multi-sectional work was published in 1957 and lasts

sixteen minutes in Kainrath’s performance (roughly the same span as

Prokofiev’s three-movement Fourth Sonata). It functions on principles

of opposition, with contrasting material in frequently abrasive conjunction

whilst remaining tonal and frequently playful. The initial adagio for

example hints at Bach before embarking on some subtle registral examination

and the material is almost obsessively revisited and chewed over. Transformative

incident from 11.00 onwards at first breaks down, with the motoric left

hand simply giving up, before slowly and magically a Bachian Chorale

emerges out of the fragmentary lines. The ending is athletic, vigorous

and triumphant. A compound of Scriabin and hyphenated Bach Feinberg’s

sonata is a welcome retrieval. The disc ends with Prokofiev, of whom

Feinberg was a friend, advocate and colleague. They also frequently

played over music together, trying out works in fourhanded arrangements

(there’s a great deal about Feinberg in Prokofiev’s 1927 Diary, published

by Faber). Kainrath is especially successful in the slow movement of

his Fourth Sonata – Feinberg himself noted in an essay on the composer

the sense of "continuous motion" that the composer cultivated

and that’s precisely the impression Kainrath succeeds in conveying.

Andrea Parisini writes a learned and analytical note

on Feinberg – his biography and musico-compositional leanings. There

is also a reprint of an article by him on Prokofiev. It’s a pity maybe

that the bigger purpose of the disc – the Feinberg exegesis – is only

revealed in the notes but otherwise this is a thought-provoking release

and especially so to admirers of Feinberg - the man and the musician.

Jonathan Woolf