During the course of a long, noisy and strenuous recording

session of the Prokofiev First Piano Concerto and the Khachaturian,

the conductor, Adrian Boult, became aware that amid the tumult the soloist

was playing Bach. He quietened the orchestra and together they listened

until the end. "I’d no idea he had it in him" Boult later

wrote to a friend in a backhanded compliment. It was the winter of 1958

and the soloist was Mindru Katz, born in Bucharest in 1925 and who died

on stage in concert in Istanbul fifty-three years later. What Boult

meant was that Katz’s reputation as a bravura thirty-three year old

purveyor of the brash and athletic powerhouse concertos had gone before

him. As was proved to be the case in Katz’s recording of Beethoven’s

Emperor Concerto with Barbirolli this was very far from being the case.

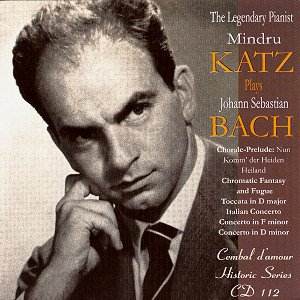

And now here is his Bach, retrieved by Katz pupil Mordecai

Shehori of Cembal d’Amour. It is strong, resilient, Romantic and persuasive.

The hyphenated Bach-Busoni with which the recital begins – the Chorale

Prelude Nun Komm’ der Heiden Heiland - has a slow, veiled, velvet

sonority that is both reverential and sustained. In the Chromatic Fantasy

and Fugue there is a strong sense of legato, of romanticised freedoms

being enjoyed within the formal constraint. His glittering treble and

right hand runs impart a sense of animation and depth and the free use

he makes of the pedal convey a real sense of grandeur and power. The

Toccata in D major has abrupt, almost contrastive playing and phrasing

– with extreme of diminuendo in the interests of internal drama. If

one responds negatively to some of this Katz is never egocentric, this

is playing of conviction borne of romantic affiliation. The Italian

Concerto goes quite well; a stately Allegro, with clarity of voice parts

brought out, and distinctly reduced dynamics in the Andante; not the

most cavalier of performances or one most guaranteed to bring the house

down but reasonable on its own terms.

The two orchestral concertos feature the Pro Arte Orchestra

conducted by the able Harry Newstone. Maybe the strings are a little

undernourished here and there but they still supply enthusiastic support

to a soloist who takes the Largo of BWV 1056, the F minor, quite slowly

and whilst one can defend the tempo and intent the execution – orchestral

pizzicati - is rather drip-drop. By contrast I enjoyed the buoyancy

of the Allegro of the D minor and the philosophic sternness of its Adagio,

realised well by Katz who releases us into the light of the Allegro

finale with generosity and affection.

Disappointing recording details are pretty much the

only thing that mars this reissue and at just under 80 minutes it is

itself conspicuously generous time-wise. Boult was right to quieten

the LPO because Katz’s Bach is the mark of a musician of stature.

Jonathan Woolf