‘Zygmunt who?’, you may ask. If, like me, you had never

even heard of Zygmunt Stojowski prior to the appearance of this disc

it may be helpful if I begin with a biographical outline (for which

I am indebted to Joseph Herter’s excellent liner notes).

Stojowski was born in the Russian sector of Poland.

At the age of 18, following studies in Cracow, he moved to Paris where

his teachers included Delibes (for composition). He attracted considerable

attention both as a virtuoso pianist and as a composer (his Symphony

in D minor, Op. 21 was included in the inaugural concert of the Warsaw

Philharmonic Orchestra in 1901.) In 1905 he went to America to head

the piano department of the new Institute of Musical Art (a forerunner

of the Juilliard School of Music) and thereafter he made his home in

New York. From around the period of the First World War he effectively

ceased to compose and devoted himself to teaching and performance.

During Stojowski’s lifetime his music was performed

by many of the leading artists of the day including pianists Percy Grainger,

Josef Hofmann and the legendary Paderewski himself; violinists George

Enescu, Jascha Heifetz and Jacques Thibaud; and conductors Walter Damrosch,

Pierre Monteux, Artur Nikisch, and Leopold Stokowski. However, despite

such advocacy his music eventually fell into almost total neglect. In

part this may have been because he did not produce any significant new

pieces for about the last thirty years of his life. More likely, however,

his music fell out of fashion because its arch-Romantic language was

no longer appealing.

His First Piano Concerto, which he dedicated

to Anton Rubinstein, was composed in 1890 and was premiered by the composer

himself in Paris the following year. Stojowski subsequently played it

with the Berlin Philharmonic and also with the Hallé in Manchester.

It is cast in the usual three movements, the first

of which opens with a brooding theme on the cellos and basses. This

is the main thematic material of the movement. Once the soloist enters

we quickly become aware that the music is written by a compatriot of

Chopin. Furthermore the sound world is not dissimilar to that of Rachmaninov

(though without the aching melancholy of the Russian master). There

are plenty of bravura passages and several passionate climaxes but much

of the music is actually rather delicate with filigree passagework for

the soloist, often accompanied by eloquent orchestral solos. In one

such exquisite passage the pianist accompanies a gorgeous, yearning

cello solo (Track 1, 9’ 17") Arguably there are a few too many

digressions into reflective byways, which do rather impede the forward

flow of the music. However, when the thematic material is so lush and

the scoring is so effective it would be curmudgeonly to complain too

loudly.

The second movement is a Romanza of great beauty. It

opens in hushed tones with lovely solos for horn and cor anglais on

which the pianist begins to elaborate. Once again, Chopin is not far

away. Though there are one or two fully scored passages, for the most

part this movement consists of delicate and highly atmospheric music

which is performed here with the utmost sensitivity by all concerned.

There are particularly notable contributions from the orchestra’s principal

cor anglais player and from the first cellist (the latter’s duet with

the soloist (track 2, 6’ 23") is just as affecting as their collaboration

in the first movement to which I referred earlier.)

The finale does indeed begin ‘con fuoco’ as marked.

This is a headlong gallop in 6/8 time in which the demands on the soloist’s

virtuosity reach new peaks. Here, for the most part, Stojowski resists

the temptation to dally and the music maintains a strong forward momentum

until the roof-raising conclusion.

The Second Concerto, written in 1909-1910 and

dedicated to Paderewski, was, like its predecessor, premiered by the

composer. This premiere was given in London, at an LSO concert conducted

by Nikisch in 1913. Two years later Stojowski gave the first American

performance in Carnegie Hall and in 1916 the dedicatee himself played

the work in the same hall to great acclaim.

The layout of this work is most unusual. It consists

of a Prologue, Scherzo and a Theme and ten Variations, all played without

a break (Very sensibly Hyperion track all 13 sections individually.)

Indeed, when Paderewski gave the work in New York it was billed as ‘Prologue,

Scherzo and Variations’.

The Prologue is a rhapsodic andante. Once again the

composer does demonstrate something of a propensity for dalliance along

the way. The music is richly romantic and lushly scored. Such passages

as the intense, memorably soaring violin theme (at Track 4, 5’ 34")

are a delight – naughty but nice!

By contrast, the Scherzo is all energy, featuring some

puckish writing for wind and brass. The piano constantly scampers around.

This is sparkling, witty music which is, I imagine, very difficult to

play well (as it certainly is here)

The theme on which the variations are based (Track

6) is a powerful, deep melody given out by the strings with piano accompaniment.

Like all good variation material it is memorable and capable of much

manipulation. The piano is silent in the first variation (Track 7),

an expansive solo for cor anglais. Thereafter, however, the soloist

leads the argument (but fully supported by the orchestra who are true

partners as the variations unfold.) With the exception of the Variation

10, the Finale, all the variations are concise with the longest of them

lasting only just over 2 minutes. Stojowski was cunning in his choice

of the theme and variations form for this allows him to show off the

technique of his soloist (to say nothing of his own skills as an orchestrator)

in many different ways and in a variety of tempi and rhythms. The variations

are inventive, resourceful and tautly constructed.

This last movement occupies over 20 minutes of the

concerto’s duration and it clearly makes copious and varied demands

on the soloist. Jonathan Plowright gives a stunning performance (as,

indeed, he does of all the music on this CD), culminating in a dazzling

yet poetic account of the long final variation. This starts off sounding

like The Sorcerer’s Apprentice but eventually the music dies

away in a subdued ending which is quite unlike the ending of a ‘conventional’

romantic concerto but most effective and satisfying.

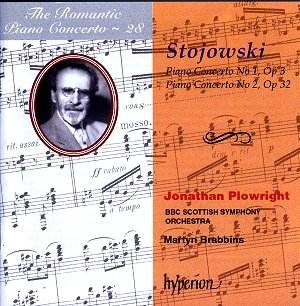

Throughout this disc Jonathan Plowright’s playing is

simply a knockout. In the power and trenchancy of his playing (when

required) he reminded me of John Ogdon at his finest. But besides calling

for sheer virtuosity these concertos offer ample opportunities for him

to display delicacy, sensitivity and fantasy and never is he found wanting.

The same is true of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra under the energetic

and perspicacious direction of Martyn Brabbins. Their accompaniments

are superb, matching the flair, dexterity and passion of their soloist.

Many CDs are issued which feature so-called neglected

masterpieces but all too often it is readily apparent that the neglect

of the works in question has not been unjustified. This is emphatically

not the case here. As I have commented, Stojowski does sometimes

linger a little self-indulgently but overall these concertos are expertly

crafted and they contain memorable thematic material – all, right, let’s

be honest, good tunes, in fact. In short, both are hugely enjoyable.

I count them as major discoveries and I have no doubt that when the

editor seeks nominations for CD of the year this release will be very

high on my shortlist.

In summary, this CD offers top class musicianship,

excellent notes, fine recorded sound and an opportunity to hear two

marvellous, scandalously neglected romantic piano concertos. Rush out,

buy it – and enjoy!

John Quinn

See also review by Rob Barnett

Hyperion

Romantic Piano Concerto Series