|

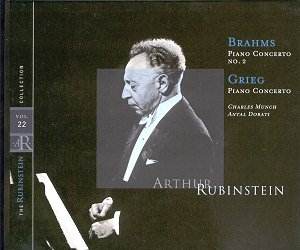

Johannes BRAHMS (1833-97) |

Brahms' Second was a great favourite with Rubinstein. He performed it with a veritable pantheon of conductors, recording it several times over his long career. The recordings began around 1930 (with the London Symphony Orchestra under Albert Coates on HMV D1746/50, which may have been the first complete recording of the work). The present 1952 account with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Charles Munch is one of the finest of his accounts. The first movement flows inevitably along, bolstered by the great power of Rubinstein's chords and his unerring sense of line. He makes light of the formidable difficulties, but this should not be read to indicate any lessening of the symphonic drama.

Rubinstein's control is an object lesson. He does not overdo the appassionato marking of the second movement, and it gains in stature for this. The Andante is exactly that (not Adagio, as is frequently the case). The highlight is the truly delightful finale, with Munch's ever-attentive Boston Symphony Orchestra matching Rubinstein's light-heartedness. Overall, this is a lovely account of this sovereign work. Occasionally, Rubinstein appears under-pedalled: the slightly dry recording means this can sound disembodied, unfortunately. Nevertheless, there is plenty of detail (from both soloist and orchestra) in evidence in this early fifties recording.

Rubinstein only started playing the Grieg concerto in the late 1930's, nearly a decade after his first recording of the Brahms Second. But he did record it five times: this one was made in 1949 and features the ever-sensitive Antal Dorati in charge of the RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra (it was originally on HMV ALP1065). The opening drum-roll really does flare up out of nothing and the piano's subsequent flourish is a real virtuoso statement of intent. Unfortunately the first movement is marred by occasional rushing (the 'molto moderato' of the tempo indication is not really in evidence, either). However, the magnificently-controlled textures of the cadenza go a great way to redress the balance.

This time the Andante feeling of the slow movement is in contravention to the composer's Adagio marking. The string sound is glorious but the recording fails to convey the full weight and importance of Rubinstein's chords. The last movement is accorded virtuoso treatment.

This is a remarkably successful coupling and one which, despite some reservations, is well worth the outlay.

Colin Clarke