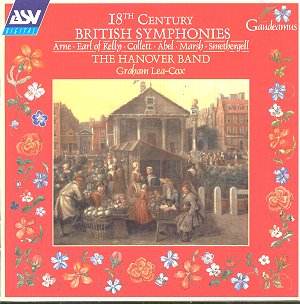

EIGHTEENETH CENTURY BRITISH SYMPHONIES

Thomas ARNE Symphony no. 4 in C minor

Earl of KELLY, Thomas ERSKINE (1732- 1781) Periodical Overture no 17 in E

John COLLETT Symphony Opus No 5 (1767)

William SMETHERGILL Symphony (1790)

Carl Friedrich ABEL Symphony Opus 10 No. 1 (1771)

John MARSH (1752 -1828) Conversational Sinfonie in E flat

The Hanover Band/Graham Lea-Cox.

Rec UK 2000, DDD

ASV CD GAU 216 [71.26]

Crotchet AmazonUK AmazonUS Amazon recommendations

A splendid disc but, whatever you do, play it at full throttle to get the full benefit of the sound, clarity and stunning enthusiasm.

At long last people are playing early music with tremendous life and not the lingering affectations and servile styles that conductors, whom I will not name, introduced. Nor do we have the dull heavy Teutonic performances that were sometimes so fashionable although I could never see why.

Cedric Thorpe Davie loved the music of the Earl of Kelly, Thomas Erskine (1732- 1781) and conducted us in it several times. Here the three movement Periodical Overture no 17 in E flat is given a fine performance. I love the vigour and the wonderful open-air feeling. My, this is therapeutic and it is discs like that which might cause music lovers to start a revival in early music provided it is played as well as this, and it must be.

Of course Cedric, along with Gerald Finzi, collected and edited early symphonies in the 1940s.

The Symphony no. 4 in C minor by Thomas Arne follows. As the excellent notes state minor keys were not often used when the set of four Arne symphonies appeared in 1767.The influence of the Court of Mannheim is evident and the work is more serious that Erskines. Remember the stir caused by Haydn when he wrote symphonies in minor keys. Mozart only wrote two in minor keys both A minor. He only wrote two piano concertos in minor keys.

The larghetto of the Arne is rather special and this serious work ends with a joyful vivace with prominent horn parts.

John Collett dedicated symphonies to the Earl of Kelly. Collett's six symphonies of 1767 are called Opus 2. This is the fifth of the set in E flat and, perhaps surprisingly, is in four movements, another possible influence, albeit later, of the Mannheim school who felt that a minuet movement should be included. The great Beethoven did this in his First Symphony but you could not dance the minuet to that movement. I can never see the sense of minuets with their often lugubrious trios in symphonies.

Collett's symphony is marked by contrast. The opening movement suggest another composer (I'll leave you to work out who). It is an allegro. I wondered why it was not taken at a quicker speed and then I heard the entry of the horns and knew why. Early composers were so good at using horns for punctuation. Some of the woodwind playing here is quite exquisite.

The andante movement lacks originality. You feel you have heard it all before.

Next comes the minuet. The Presto follows but it is not a presto but somewhat reserved and plodding. After all, presto means fast. This is not.

William Smethergill published two sets of symphonies as opus 2 and opus 5 respectively. He lived from about 1770 to 1805 and was active in London.

This conventional symphony published in 1790 takes a little while to take off. But it has a felicity that suggests Mendelssohn and an intimacy at times which I admire. It also has a warmth almost predicting the romantic era of music. The central Andantino has a disarming simplicity and falls easily on the ear. The presto finale is in three time (!). Again it is only an allegro albeit most acceptable.

Carl Friedrich Abel was German but spent the last 28 years of his life in England. His third set of symphonies catalogued as Opus 10 appeared around 1771. This is the first of the set and is in E, a rare key for those days. Its subdued opening precedes a lively allegro evolving from a super crescendo. It is a good movement with a lot of activity and sensible bustle. It also has a refinement which is not stuffy. There is a moment of brief calm on slow moving strings which was like an oasis in a desert. The controlled vigour is admirable. What is here is elegance that Mozart was later to capitalise on. The andante seems to experiment with modality and recalls Handel but without all those blessed ornaments . . . thankfully!

Ornaments are a nuisance and, to compound the issue, they are taught as musical rules rather than musical history.

And in these performances no tinkling harpsichord!

The finale is an allegro and is very courtly and perhaps slightly pompous but it chatters away with that wonderful enthusiasm and brims with confidence. It stirs the arms to conduct and the foot to tap. I love the way the music becomes subdued but remains its vitality. That's class!

Now, here's a strange title A Conversational Sinfonie in E flat by John Marsh (1752-1828). For some daft reason the composer issued it under the name of Sharm an anagram of his name. The work is said to be for two orchestras, another daft concept.

Marsh wrote 39 symphonies, many of which are lost, and so becomes the first prolific British symphonist. This one was composed in Salisbury in June 1778 and sets off low instruments against high ones hence the conversation. But this device becomes so predictable. Nonetheless it is as good as any of the works on this disc. His material is the most notable. His melodic lines the most satisfying and the construction the most sound. The second movement uses the Scottish snap, another daft name, and the finale takes us into the glorious English countryside with hunting horns and, of course, no motorways, cars or pollution! Free, clear air. Slightly banal though, perhaps.

Much to enjoy on this disc.

And why did early composers love the key of E flat more than any other?

David Wright