|

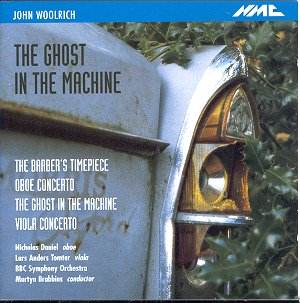

John WOOLRICH (born 1954)

|

John Woolrich has so far written a considerable amount of works in almost every genre. His varied output includes a number of orchestral works and of concertante pieces. The works in this generous release include two orchestral pieces and two concertos spanning some ten years of his busy and prolific composing career.

The earliest piece, The Barber's Timepiece, was written in 1986 for the orchestra of the National Centre for Orchestral Studies. It is a fairly short piece contrasting a slow-moving, chorale-like song with a ticking, grunting accompaniment in which irregular percussion gestures are prominent. Indeed on two occasions, percussion breaks try to stop the song without really succeeding though the music eventually peters out and the piece ends rather inconclusively. This is a fine, colourful concert opener that should be popular with orchestras and audiences as well; and a good introduction to John Woolrich's highly personal sound world.

The Ghost in the Machine, completed in 1990, is a rather Mahlerian processional described by the composer as "a fifteen minute accelerando for large orchestra". The main subject is stated by the horns in the very first bars and re-appears frequently in various guises later in the piece. Much as in The Barber's Timepiece, the main material and its variants are contrasted with ever-changing, varied orchestral textures including Woolrich's beloved "ticking machines". At the climax, the clock's spring unwinds and the music then moves into a calmer coda in which a solitary trumpet sounds some sort of Last Post over diaphanous string textures. A powerfully gripping piece in spite of its somewhat quizzical title.

The Viola Concerto is Woolrich's second piece for viola and orchestra. The fairly well-known Ulysses Awakes of 1989 is a highly personal reworking of Monteverdi whereas the Viola Concerto, though still secretly alluding to some older composers, is an original, again deeply personal work. It is scored for a classical orchestra (double woodwind, two horns, two trumpets and an surprisingly limited percussion section). The composer describes it as "a cycle of seven bleak and brooding songs-without-words". Indeed the singing qualities and the warmly elegiac tone of the viola are much to the fore and "the orchestra echoes its song in predominantly soft and gentle colours". True, this is a beautifully eloquent, though much restrained work which is one of the finest viola concertos I have ever heard. A truly moving piece that vastly deserves wider currency.

The most recent work here is the extraordinary Oboe Concerto completed in 1996. In full contrast with the Viola Concerto, the Oboe Concerto is scored for a very large orchestra with an almost extravagantly manned percussion section including some rather unusual "instruments" (e.g. tin cans of various sizes, brake drum, scaffold bars, car wheels, spring coils and a sawn-off oxygen cylinder). Moreover, the soloist leads a group of three oboes and one soprano saxophone ("their more extrovert cousin"). The miracle is that Woolrich uses this vast array of percussion with a remarkable economy, and that the work never sounds as an extravagant sonic display. Quite the contrary, Woolrich uses his assembled forces with parsimony, taste and to good effect. The overall mood of the concerto is one of singing lyricism though it has its more dynamic moments (including some favourite "clock mechanisms"); but again song seems to me the predominant characteristic of the piece. The Oboe Concerto also shares many common features with the Viola Concerto and the orchestral pieces. Foremost among them, Woolrich's ability to draw seemingly endless variation from fairly simple basic material and to develop and sustain his invention and imagination throughout. The Oboe Concerto definitely deserves to be widely known and appreciated, though the sheer vastness of the forces called for might prove a liability.

This cross selection of John Woolrich's output is superbly played by all concerned: Nicholas Daniel is his inspired self in the wonderful Oboe Concerto while Lars Anders Tomter manages the demanding viola part with aplomb and highly accomplished technique. Martyn Brabbins and the BBCSO show themselves dedicated supporters of Woolrich's demanding, though highly rewarding music.

If - for any reason - you think that Woolrich's music is not for you, then give this most welcome release a try, and you will find that John Woolrich definitely has things to say and knows how to say them in the musically most satisfying way.

Warmly recommended.

Hubert CULOT