|

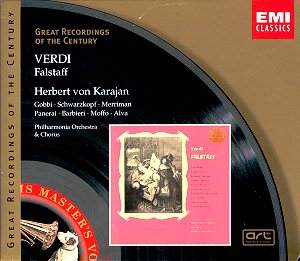

Giuseppe VERDI Falstaff Tito Gobbi - bass-baritone (Falstaff) Luigi Alva - tenor (Fenton) Rolando Panerai - baritone (Ford) Tomaso Spataro - tenor (Dr Caius) Renato Ercolani - tenor (Bardolfo) Nicola Zaccaria - bass (Pistola) Elizabeth Schwarzkopf - soprano (Alice Ford) Anna Moffo - soprano (Nannetta) Nan Merriman - mezzo soprano (Meg Page) Fedora Barbieri - contralto (Mistress Quickly) Herbert von Karajan - conductor Recorded 1956 Crotchet AmazonUK AmazonUS Amazon recommendations |

What with John Eliot Gardiner's version on Philips earlier this year (review) and now the Abbado account for DG with Bryn Terfel (after its performances at this year's Salzburg Easter Festival) (review), this Verdi centenary year is reminding us of the headier, healthier and more active years of the classical music industry; precisely those years at the start of which came this benchmark account of the composer's magical swansong opera. Admittedly we had other accounts earlier or in between which are impossible to discount, such as those of Toscanini (NBC 1950) and Solti (RCA 1963), but the mouth-watering cast-list for this Karajan version made at the height of the Walter Legge years says it all, particularly the male line-up of singers. Although Gobbi always maintained that the character of Falstaff is realised in the opening monologue in Act 3, the kaleidoscope of vocal colour he brings to his lecture on honour given to his henchmen in Act 1 sets in motion a vividly charismatic portrayal. He is supported by the thrilling sounds of the Philharmonia, who are whipped to a frenzy by Karajan in its postlude at the end of this first scene, just to select one of many gripping moments.

Karajan's Falstaff was influenced much by Toscanini's interpretation, whose performances he both heard (in Vienna in 1929) and assisted at (Salzburg 1935-37), though in this recording 20 years later he had the advantage of an orchestra truly at its peak, with a particularly blazing brass section. Where the two maestri differ is in refinement, for where Karajan is glossily smooth, Toscanini has the rough edges for the opera's earthy humour. Somehow Karajan's is always a restrained, controlled laughter, despite his view of Falstaff as the pinnacle of operatic comedy. The most vital ingredient for this opera is its sense of ensemble, above all the clarity of its diction, and there are some breathtaking moments, for example the Garden Scene (Act 1 Scene 2) with the women's impeccable staccato-on-the-breath singing, the conclusion to the same scene with the lovers riding high above the ensemble, and of course in the final fugue, 'All the world's a stage', which ends the opera. Moffo and Alva are charmingly mellifluous in their moments of love, either together or alone, aided by the magical sound of Dennis Brain's horn solo at the start of Act 4 Scene 2, one of his last recordings before his tragically early death a year later. Barbieri's voice as Mistress Quickly in the 'Reverenza' duet with Falstaff in Act 2, the kernel of the opera's drama, is extraordinary and bubbles plumply. Panerai's creamy tones in his follow-up duet with Gobbi, change to terrifyingly uncontrolled fury in his monologue after the latter's exit, whilst the mockingly bright-voiced Schwarzkopf radiates in her moments alone with Falstaff leading to the tensions of the basket scene. As the sopping wet old buffer crawls out of the Thames at the start of the fourth act just listen to the Philharmonia, after which enjoy the vocal genius of Gobbi.

Incredibly Falstaff used to have the reputation as a tuneless opera, but nothing could be further from the truth. Melodies pour forth one after the other and are breathtakingly scored by the octogenarian composer. This is truly one of the 'Great Recordings of the Century'.

Christopher Fifield