Crotchet

AmazonUK

AmazonUS |

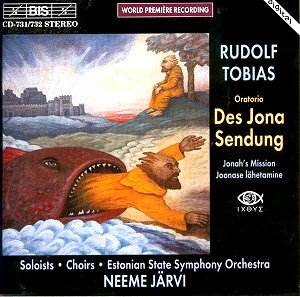

Rudolf TOBIAS

(1873-1918) Des Jona Sendung (Jonah's Mission) - an oratorio in a Prologue and Five Scenes (1909) Restored and arranged by Vardo RUMESSEN Pille Lill (sop) Urve Tauts (mezzo) Peter Svensson (ten) Raimo Laukka (bar) Mati Palm (bass) Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir Tallinn Boys' Choir Ines Maidre (organ) Estonian State SO/Neeme Järvi rec 23-29 June 1995, Estonia Concert Hall, Tallinn world premiere recording |

Although I knew of Tobias from the two Chandos Estonian orchestral CDs (issued in the 1980s and still available) I had never troubled to explore more deeply. The 'trigger' for mining this vein came with ProPiano's CD of Vardo Rumessen's playing the preludes of Tobias's countryman and contemporary, Heino Eller. After having reviewed the disc I made contact with Mr Rumessen, who, in addition to being a pianist of Hamelin-like power and sensitivity, is also a member of the Estonian Parliament and an expert on Estonian classical music. He was kind enough to send me for review the piano music of Tobias (to follow) and Tubin as well as the present oratorio which he realised from original materials.

Tobias scowls at us with ram-rod insolence (the very image of the young Sibelius) across the years in a photograph on the back of the booklet. He was brought up in a church-attending family. With his musical leanings recognised he attended the St Petersburg Conservatoire where he was the first Estonian to study with Rimsky-Korsakov and to graduate in composition. In 1904 he moved to Tartu becoming involved in oratorio performances and making links with the then Estonian Nationalist movement.

It was in the artistically limited world of Tartu that he began work on Jonah's Mission. The idea gestated as he travelled through Western Europe until it was completed in its first version in Leipzig in 1908. Tubin's Jonah stands as a fallible and believable being, torn between duty, fear and compassion. The 'Believers' Congregation' represented by the massed choirs are the suffering peoples - an analogue for the people of Estonia. A children's chorus offer unsullied hope of renewal. Tobias intended to express God's Mercy as the redemption for the sins of the world and ultimately the Second Coming. This is very clear from the radiant closing 'Amen's. The sung texts (in German - what a pity they were not in Estonian but Tobias certainly wrote the work in that language) are drawn not only from the Book of Jonah but from many other biblical sources. In a superscription to the score the composer proposes the work as one that scourges a superficial attitude towards religious truths.

The work was premiered in Leipzig in 1909 but what should have been a great coup was a failure with the composer unconfident and the forces trimmed to ridiculously small proportions rather like the banishment of the premiere of Arthur Bliss's Beatitudes to a Coventry theatre complete with feeble cinema organ in 1966.

Vardo Rumessen (who provides the booklet commentary) reconstructed the Jonah score in the ferment of Estonian nationalist renaissance in 1986-89 as the Soviet 'empire' crumbled. Peeter Lilje conducted its true premiere on 25 May 1989 in the Estonia Concert Hall.

The work is in 38 sections, each separately tracked. Musical themes are printed in the booklet alongside a section by section annotation. The booklet also prints Tobias's own notes and his thoughts on 'landmarks' in the score.

The music is something to shout about. Hearing it now in a performance that flames and smoulders leaves one in awe. This is no somnolent run-through by an orchestra and chorus with a contract to fulfil. No 'conveyor belt' emotions are present here. Preparation must have been painstaking but not so much that excitement was damped. Indeed the Hall is a lively acoustic - amongst the world's best, on this evidence.

Time after time this work dashes in with fury and with passion. Something burns brightly in the voices of the choir. There are peremptory calls to action which have about them the fervour of Vaughan Williams' Sea Symphony. The massed singing often recalls Havergal Brian's Siegeslied Symphony No. 4 (as in Rachepsalm track 1 CD2). While there is a touch of Handelian (not to say Germanic) monumentalism it is always lifted by an individual orchestral imagination which is quite unlike any other composer I know. His writing for woodwind is always glorious with 'voices' rising out of the most overbearing of textures. Listen to the oboe calling irresistibly and confidently in the Heilig track on CD2 in Scene 3, in track 15 before the children's chorus where a saxophone-darkened wind choir add a deliciously sinister overtone. In track 35 the loving writing for flute and oboe is rather like a dissolutely updated Bach cantata. It is said of Schoeck's Penthesilea that the orchestral sound had a 'bronze' sound. Tobias, in this work, favours the baritone register. Once we sit back and wonder at Tobias's tenderness (e.g. in the pastel gentleness of the Chorus Mysticus sections) he then flattens the listener with touches of the gloriously wild excesses of Havergal Brian's Gothic symphony or of Berlioz's thunder. He occasionally overdoes the cymbal crashes ... but rarely. The soloists are an impressive team - note the fierce confidence of the Jonas Aria (Scene 3). There are no weak links in this music or in its execution.

In Scene 4 the corrupt and doomed Nineveh is portrayed in the carousing drinking chorus which knocks spots off Rutland Boughton's 'boy scout' efforts in The Queen of Cornwall and which approaches celebration from a different angle than Granville Bantock's contemporary Omar Khayyam trilogy. Interestingly both Bantock and Tobias make effective use of the tambourine in these carpe diem episodes. The sequence of scenes have a parallel with Walton's Belshazzar's Feast: Babylon/Nineveh both due to be cast down for depravity - both weighed in the balance and found wanting.

The work can also be viewed in the context of other similarly fervent Scandinavian choral works. Sibelius's still terribly undervalued Kullervo Symphony and Uuno Klami's dark and resolute Psalmus. Each express aspects of the same nationalistic inferno that lights up Tobias's extraordinary work.

I must gripe however about the sung texts. They are printed in translation but, unhelpfully, the translations are each printed separately so that the reader has to flick between sections of the 96 page book.

In this work all is resolved (or is it?) in the final section with a direct-speaking theme akin to Peterson-Berger which floods these pages with sunlight - a lucid radiance amid which the bell tolled 'amen's ring out. Franz Schmidt's Book With Seven Seals is similar in spirit to Jonah and also ends with a great upwardly rushing sequence of 'Kolossal' choral Amens. The Tobias is a work to be counted in that luminous company. In fact, overall, the greater variety and melodic resource of the Estonian leaves me suspecting that the Tobias may have a longer shelf-life once it secures some attention. The 2000 Henry Wood Proms featured the Franz Schmidt work - confounding my prejudices. Can we now hear Des Jona Sendung in the same series?

Rob Barnett