|

Lowell LIEBERMANN (b.1961) Crotchet

AmazonUK

AmazonUS |

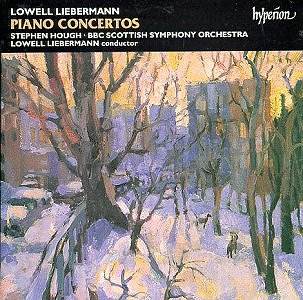

Just as I was about to review this CD (Sept 2001) I had a conversation with the young British pianist Tony Hewitt. He told me, with some trepidation, that he was just about to play the 2nd concerto in New York. I looked through the score with him. We agreed that the concerto is a true masterwork. The cover of the booklet is adorned with a winter painting by Fort Tyron Park in New York by Ben Moore. Liebermann was born there and is based there. In the distance are the twin towers of New York so savagely destroyed just recently. How will the music, we wondered, of this New York-based composer be changed by this tragedy. The wide-eyed innocence of some of it, the Romantic belief in a safe musical haven originating in the past might be shattered. Will things ever be the same again? How will this prolific and brilliant composer develop? I look forward to finding out, because what these works have in common is a phenomenal skill, technique, confidence and, I use the word not lightly, genius, in the 2nd concerto at least.

Stephen Hough supplies the extensive and analytically detailed programme notes with musical quotations and perceptive sign-posting. It's just a pity that he fails to tell us exactly when the works were actually composed. He writes: "Liebermann's music can be divided into two periods. The first contains works of a contrapuntal angularity, where themes take uncompromising atonal paths; the second period works are guided more by harmonic significance, following maps of tonality, although arriving at unexpected destinations". He goes on to imply that the language of the second period will be easier for the listener to grasp. It's a pity that we start with such a viewpoint.

The First concerto is, as he describes it, in the steely style of "lanky, adolescent athleticism". I was much taken with it. There are two outer Allegros with a disturbing mood of bleakness in the middle movement. Its dedication to Sorabji is most curious and goes without explanation. I can't think that the older composer would have had anything in common with it. There is a dark side to this work with its use of, Hough tells, "two plague-tunes", one being the 16th Century melody 'Fortune my Foe', in each movement. This is a tune I know well but I could only pick it out in the 3rd movement called 'Maccaber Dance'. Maccaber, a Scottish 17th Century explorer was described as being 'half a skeleton', it acts anyway as a good metaphor for the concerto. The 2nd movement was "inspired by the section 'Dream Figures' in De Quincey's 'Confessions of an opium eater'."

The 2nd Concerto is seemingly from the late 80s. It is astonishing. A twelve tone row is set out in the booklet. This is used both melodically and harmonically. It is also used in its inverted form in the 2nd movement. Liebermann bases a set of Variations on it in Movement 1. If this sounds a touch academic then, forget it; the construction is the composer's business if you like. This is a Romantic, virtuoso concerto in succession to Rachmaninov, Dohnanyi and Howard Hanson. My own problem with it is that in a four movement work a 3 minute Presto-Scherzo placed second is unnecessary (lovely and fun though it is). Indeed I played the concerto through omitting that track and it worked even better, keeping the overall tension much more successfully. The 3rd movement is a Passacaglia using the tone row. The fourth is fast and has a terrific ending culminating in a double octave rising piano passage of great excitement accompanied by blaring trombones.

The recording is annoying in one respect. The volume control, which you set for the 1st movement of each concerto, will have to be turned up for the slow movements. I have observed this on other recordings from Hyperion. If you have a remote control for your stereo then it will not worry you. Just beware when the faster movements begin with a bang, if your volume level has not already been reduced!

It is also curious that a disc weighing in at less than an hour could not find a place for all twelve of the attractive but possibly inconsequential 'Album for the young' pieces. Of the six recorded, Number 4; 'Rainy day' was originally written when Liebermann was a child. It is highly evocative.

Stephen Hough is a perfect advocate and having the works recorded under the composer's seemingly ideal direction is wonderful. I would love to think that Liebermann might be asked back to record more. What about the Symphony he wrote aged 21 which Hough writes about with such mouth-watering interest.

Gary Higginson