|

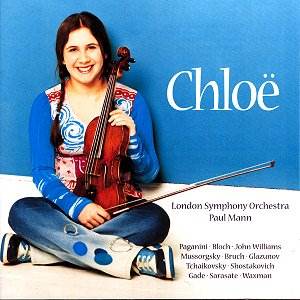

CHLOË Paganini - La Campanella Bloch - Nigun Gade - Capriccio Williams - Theme from Schindler's List Mussorgsky - Gopak Bruch - Adagio appassionato Glazunov - Meditation Tchaikovsky - Valse-scherzo Shostakovich - Romance Sarasate - Romanza Andaluza Waxman- Carmen Fantasy London Symphony Orchestra/Paul Mann Recorded 2001 Crotchet AmazonUK AmazonUS Amazon recommendations |

Guildford-born Chloë Hanslip is fourteen years old and has played the violin since the age of two. Menuhin took her on at his school from her fifth to seventh years, then she went to Zakhar Bron, who has taught Vengerov. Her mentors at masterclass level include Mintz, Haendel, Accardo, Ricci and Vengerov. Her public appearances began at the age of four at the Purcell Room, and over the next six years took in most of Europe and North America. Her career as a recitalist is just as extensive and in the film Onegin she played the role of what she is in real life, a child prodigy.

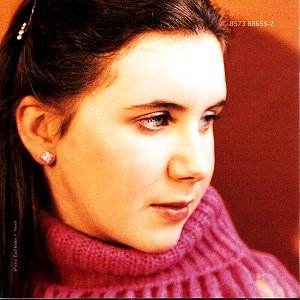

It is fairly fashionable among the cognoscenti to quickly condemn the child prodigy, but a look back in musical history would compel those who do so to include a huge list of musicians. What today is generally so reprehensible is all the hype and publicity that goes with promoting the performer, and it is a blessing that (so far at least) Chloë Hanslip is neither photographed emerging dripping from the sea, violin in hand, nor caressing it whilst suggestively draped over a chaise longue. Indeed her photos range from a charmingly pig-tailed jeans-wearing tomboy to a sophisticated concert apparel-wearing young lady with her loaned Guarneri del Gesu violin prominently displayed.

Prodigies by definition play prodigiously difficult music, much of it technically challenging. Whether such repertoire has any depth of feeling and is to be dismissed as pure froth is arguable. The eleven tracks here make a laudable attempt to go further than a mere firework display, though it cannot be denied that she is a fearless player, agility and fluid technique in both left hand and right arm are impressive. Her emotional experience at fourteen can only be limited and she cannot be blamed for that, so the warmth of her sound and the sustained line she achieves in Max Bruch's beautifully melodious Adagio appassionato is admirable (admittedly I might be considered biased as Bruch's biographer but I still think it was an inspired choice on someone's part to include such an unknown piece). The range of works covered on the disc is fairly varied starting from the immediate impact of the Paganini Rondo - no warm-up act or waiting for Chloë, hers are the first sounds you hear. The sentimental music of John Williams and Glazunov pales in comparison to the Bruch Adagio despite Chloë's best efforts, though the Jewish idiom of Bloch's Nigun is stylishly captured in her phrasing and depth of tone. Tchaikovsky's and Gade's music is happy enough, a pair of Romances by Shostakovich and Sarasate continue in a more self-indulgent vein, after which, continuing the Spanish theme, the whole is wrapped up by a stunningly thrilling performance of Waxman's pyrotechnical but clever treatment of familiar themes from Bizet's opera. Throughout she receives assiduously directed support from Paul Mann and the LSO, but it is only Shostakovich who gives the orchestra a sizeable chunk of the limelight on its own, and so the strings seize it gladly as if to reinforce the point that generally what happens to students of the violin is that these days they become either orchestral players or teachers, if not computer programmers. This is a debut recording, interestingly engineered by Mike Hatch of the always dependable Floating Earth and, as it happens, married to another highly gifted British violinist, Tasmin Little. With careful handling of her career, Chloë Elise Hanslip will hopefully not become the Charlotte Church of the violin.

Christopher Fifield

Chloe now holds a 5 record deal with Warner. She will record couplings of familiar concertos with comtemporary music