|

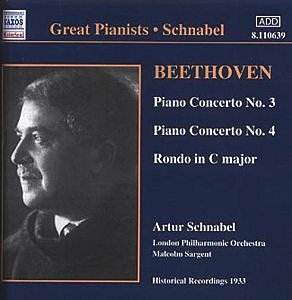

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN

(1770-1827) Piano Concerto no. 3 in C minor, op. 37* Piano Concerto no. 4 in G, op. 58*, Rondo in C, op. 51/1 Rec.17.2.1933, 16.2.1933, 13.4.1933 at EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 1 (Concertos), No. 3 (Rondo) Crotchet AmazonUK AmazonUS Amazon recommendations |

The last time I heard one of the Schnabel Beethoven Concertos was in a record shop so I can't tell you which transfer it was. But I do remember the orchestral sound being so lifelike that I made a point of remaining in the shop till the piano entered. Alas, it was a tinny, clattery disappointment. This version has a husky, rather raucous orchestral sound, especially in the tuttis, but the piano tone, however limited in frequencies, has a certain beauty and translucency. Indeed, this is the first time I have been able to associate Schnabel with a beautiful sound. A certain aggressive clanginess has always seemed to me inseparable from his music-making as preserved (not necessarily his fault of course, though he was never noted for putting tonal beauty or technical finish before musical truth). It would be nice to think that Mark Obert-Thorn's transfers have likewise privileged musical truth by finding the beauty in Schnabel's tone even at the expense of the orchestral sound but does it have to be one or the other?

The gem here is the Rondo. Here we have a Beethoven poised to jump from rough humour to delicacy and then to the sublime all at a moment's notice and all the while maintaining a perfect musical line. Of the Concertos, I most of all appreciated the cadenzas for this same freedom of expression within a disciplined framework. For the rest, I have to say that there are some myths which seem still to speak to us directly today, for others we have to make "allowances", to listen "through" the various inconveniences and recreate imaginatively the myth for ourselves.

The greatest inconvenience was that Schnabel was notoriously scared stiff of recording and this shows not so much in wrong notes, which don't worry me tuppence, but in rhythmic tightening when he is afraid things might go wrong. Sargent is none too helpful, especially in the first movement of no. 4 where, perhaps nonplussed by so many tempi for the repeated-note figure he starts adding further tempi of his own. Listen to the start of the development and imagine the soloist waiting and wondering which of these tempi (if any) to enter with himself. These are not the vagaries of a Furtwängler, with an inner logic to them, they are just the combination of the pianist's nerves and the conductor's lack of concentration. Where the going is good Sargent can be positive, a crisp opening ritornello to no. 3, for example, but he was hardly on Schnabel's philosophical wave-length and it is a pity that Boult was not chosen instead (or that the cycle had not been recorded in Vienna with Weingartner or Walter). Also, give the strings a scrap of lyrical melody and they swoon all over it with portamenti which sound most out of place to modern ears. It's strange that the LPO, which was Beecham's creation and very much made in his own image, should have still been playing like this since it was not a Beecham characteristic at all, or was it chock-full of deputies on this occasion?

Listening "through" this, there remains Schnabel's sheer dedication to the music, his sense of the shape of every phrase, but I feel that this is an issue best left for students of the piano and of pianists. Some months ago I was praising the version of no. 4 by Schnabel's pupil Clifford Curzon (Decca Legends 467 126-2). This I would say is an example of a myth which can still be perceived as such without difficulty. I've just finished rave reviews of Naxos's two Moiseiwitsch discs and I am only sorry that I have not found similar revelation here.

Oh, but perhaps I've left out the fundamental point. It's easy to take for granted the fact the Schnabel's Beethoven has such a very Beethovenian sound, strong, authoritative, clear but rich and direct. Nalen Anthoni's interesting notes mention William Murdoch, York Bowen, Mark Hambourg and Wilhelm Backhaus as pianists who had recorded these works previously. I should be very interested to hear all of them but I have the idea that all except the last would seem, in their attitudes to tempi and sonority, to come from another age. It was Schnabel who taught us that Beethoven sounds like this and subsequent performers have all built on the lesson. So well as to spoil our appreciation of the source of it all.

Christopher Howell