|

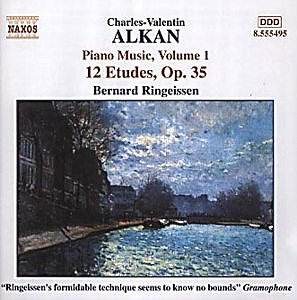

Charles-Valentin ALKAN (1813-1888)

Piano Music, Vol. 1: Le festin d'Esope, Op.39 No.12 Scherzo diabolico, Op.39 No.3 12 Etudes, Op 35 Recorded at Tonstudio van Geest, Heidelberg, 1990. First released on Marco Polo (8.223351) in 1993. Crotchet AmazonUK AmazonUS Amazon recommendations |

Alkan came from the great nineteenth-century tradition of composer pianists that included Chopin. Liszt, Schumann, Brahms and Busoni. For a time he shared the lavish praise heaped upon these giants of the keyboard, but in 1848 rejected the life of a travelling virtuoso and spent many years as a virtual recluse. His reinstatement as a composer of remarkable depth and sensitivity has been gradual, but is by no means complete. With a pianist of Ringeissen's calibre, this new Naxos series is a substantial step towards wider recognition.

The first two items prepare us for the sheer technical brilliance that practically all Alkan's works demand. Both are clearly intended to wow the audience, and succeed in doing so without virtuosity becoming an end in itself: this is far more impressive stuff than mere pianistic fireworks - Le Festin d'Esope, a rich feast of 25 variations on an original theme that sounds very like the nursery song Baa baa black sheep, develops in many unexpected ways. Childish thoughts are quickly set aside for a thoroughly adventurous treatment of the innocent theme; even humour - not a conspicuous component of romantic piano music - is not absent: several of these variations raise a genuine smile.

The second, Scherzo diabolico, comes closer to Liszt's energetic concert studies but, devilishly difficult though it undoubtedly is, adds up to considerably more than keyboard gymnastics. It is, however, in the 12 Etudes in all the major keys that we encounter Alkan at his most innovative and powerful. There are occasional echoes of Chopin but, needless to say, these are not studies in the same sense as those by Czerny or Bergmuller, though all of the first nine address specific aspects of technique. As a coherent cycle the Etudes test the interpretative resources of a mature recitalist on all fronts, from expressive cantabile to the dramatic metrical changes in the dramatic No, 12 in E flat major, a challenge calmly and creditably met on this record. The scores were scrupulously written and meticulously marked by the composer, and Ringeissen intelligently avoids creating additional hurdles by conspicuously parading his virtuosity. The playing is neat and observant and we are left with a convincing exploration of the mind of a remarkable musical personality.

If the reader may excuse a personal note, when I studied piano with Grzybowski I tentatively suggested we take a peek at Alkan. "No", he said. "Why attempt to pick a bouquet of oak trees when there are so many beautiful flowers around?" I now realise that this was not meant discouragingly, or as a criticism of Alkan. Any pianist who can play his works well, and with such deep understanding as Ringeissen, is a rare bird, and must be treasured. The piano sound is excellent, and I eagerly await forthcoming releases in this series.

Roy Brewer