This set is the first full recording of this interesting

work. A few extracts have been previously released on Danacord’s Danish

Songs (DACOCD348) but this composer has been largely neglected outside

Denmark and hearing this work I wonder why. He clearly follows the traditions

of the early German school both in structure and orchestration and a

style close to Mozart or Rossini. The arias could have come from the

pen of Schubert. Certainly this shows that Weyse was very knowledgeable

of the music of the German and Italian masters. The composer’s background

explains why this is so.

Christoph Weyse was born in Denmark, close to the German

border near Hamburg. In his teens he arrived in Copenhagen as a young

virtuoso pianist to live with Schulz, a composer and conductor of the

Royal Theatre. The introduction to Schulz and the move had been due

to the influence of professor C F Cramer of Kiel who was the son of

the King Frederik V’s court chaplain. The young Weyse had visited Cramer

asking for help to become a musician and so the move to Copenhagen had

been the outcome.

Weyse’s early years in Copenhagen as apprentice to

Schulz led to his acceptance for the post as organist in the German

Reformed Church (1792) at the age of eighteen. He went on to play at

court, perform piano concertos by Mozart and become a member of one

of the city’s private musical clubs. During the early part of his career

he wrote songs and seven symphonies (recorded under the Marco Polo label).

Much of this material was recycled for use in later years, often as

overtures and theatre interval music. He was a master at improvisation

on the piano.

Weyse’s interest in the theatre was helped initially

by Schulz and later when Kunzen replaced Schulz as conductor at the

Royal Theatre. Kunzen’s wife was a singer with a wide knowledge of musical

drama. On a prompt, Weyse studied Mozart and Gluck operas in detail

and decided he wanted to write for the stage himself.

In 1800 he came across Bretzner’s Singspiel in a shop

which he bought. As Weyse describes—

"The Sleeping Draught" seemed to me to be

the best of them, on which I might try my luck. And now in the course

of the summer I composed the whole first act up to the end of the finale,

where the words did not suit me, and the first four numbers of Act Two,

but without writing any of it down."

Weyse played through his new music to Kunzen who was

complimentary and urged him to finish the piece and also have it translated

into Danish. The poet Oehlenschläger (fanmous for Nielsen's Aladdin

and the finale of Busoni's piano concerto. Ed) adapted and translated

the piece, finding it easy to build on Bretzner’s frothy plot. The translation

lay for seven years before being scored. In 1807 Kunzen presented

Don Giovanni with great success at the theatre and which Weyse went

to see. This event was the catalyst to motivate him into completing

The Sleeping Draught two months later. Around 1780 five out of

six Berlin operas were based on Bretzner’s comedies, the man was so

popular. From this period onwards, Bretzner introduced a format different

from his early texts and included elements familiar to the Italian Opera

Buffa where characters interact with each other. There is no such

interaction in the early German Singspiel. Thus, Bretzner gave German

composers the opportunity to write a new type of music, where several

singers are acting and singing at the same time and became a dominant

feature of finales, and so Bretzner provided the German Singspiel packaged

in the Italian manner.

Weyse built on this new format and The Sleeping

Draught was his first Singspiel, the result being nothing less than

superb. With great precision he hit the right tone in captivating the

essence of Bretzner’s story as well as displaying the knack of writing

a Singspiel. Here we have the heroine’s lyrical aria, the hero’s bravura

aria, the comic buffo aria, and the distinctive lyrical romance that

was to become a Weyse speciality. There are also several ensembles and

two great act finales, of 20 minutes and 120 minutes’ duration. The

overture comes from one of his symphonies (the final movement of the

2nd Symphony). The notes describe the aria content in detail.

He went on to satisfy greater ambitions and write true

operas for the stage, some with spoken dialogue. These were Faruk

(1812), Ludlam’s Cave (1816), Floribella (1825), and

Kenilworth (1836). Although some of their songs were popular

the public never really identified with his later operatic style, for

whatever reason. This is a pity because The Sleeping Draught

held much promise of better things to come.

Act 1 opens in the house of Brausse, a surgeon.

The family are found sitting at dinner and entertaining

Walther, the fiancé of their daughter Charlotte. Her father,

Brausse, is to amputate the leg of a farm-hand the following day and

asks Walther, who pretends to be a surgeon, to carry out the operation

on his behalf. Walther has to confess that he is not a surgeon after

all but is a lawyer. At once the furious Brausse asks him to leave the

house. Walther who has just previously exchanged a ring with his beloved

protests whilst Charlotte and Brausse’s niece, Rose, protest and try

to calm him down. The other member of the family, Saft, has been busy

eating throughout the Act ignores the commotion around him and continues

with his greedy scoffing.

Brausse has plans for his niece Rose to marry Saft

but she has ideas of her own and is in love with a hunter, Valentin.

Saft is not over-interested in Rose and considers that to marry a lawyer

will ensure there is always food on the table.

In preparing for the operation for the following day

Brausse gets the anaesthetic ready –drops of opium in a bottle of wine.

The farmhand, Hans, calls asking the surgeon to attend to men injured

in a brawl at the inn. Brausse rushes out with Saft. On cue, Walther

comes in from the garden to tell Charlotte that the law states that

parents cannot object to a marriage without valid reason. In an attempt

to celebrate the situation in the surgeon’s absence, Rose pours a glass

of wine for Walther. After drinking the wine and singing a song Walther

sits down tired. The hunter arrives to woo Rose, but a knock on the

door (Saft) causes them to hide in the hearth with Valentin disappearing

out of the window.

Saft enters to collect the bottle for Brausse and tell

Rose of his love despite her refusal. Once Saft has left Valentin returns

to try to get the now unconscious Walther out of the house. A miller’s

flour chest will be useful to their aid. Hearing that Saft and Brausse

are on their way back everyone hurries out. The girls shortly return

to say they only left because they thought the house was haunted. A

comic situation develops as Valentin ‘haunts’ them.

Abelone, the miller’s wife with whom Brausse is secretly

in love, appears complaining of a swollen finger. Brausse steals an

embrace from her when the miller enters. He shows his anger at seeing

the two together. A comic situation develops as a fight ensues. Saft

goes into the pantry straight into the arms of Valentin and Rose. The

lights go out and the act ends in chaos.

Act 2 is 20 minutes shorter and thus follows theatre

convention.

Scene 1 is a court outside the miller’s house, the

following day.

The miller and his men sing of the merry morning but

are reminded about the previous evening’s fiasco. Abelone in a song

sings that jealousy can kill love and it shouldn’t come between them.

Scene 2 is an interior of Brausse’s house.

Charlotte believes that her beloved Walther is dead

and Brausse enters to witness her grieving. When Charlotte leaves, Rose

enters and confirms that she is to marry Valentin, not Saft. Saft tells

Brausse that he will not stand in the way of Valentin, helped by a threat

from Valentin, and so Brausse reluctantly gives his consent.

Scene 3 is a room in the Miller’s house.

Abelone is discovered spinning. Charlotte and Rose

enter to ask advice now that Walther is dead. They see Brausse approaching

and hurry into the garden. He enters to look ostensibly at Abelone’s

finger, but she tells him to leave at once for the Miller is on his

way. Brausse hides in a flour chest while Abelone continues her spinning

and singing a ghost ballad. The miller tells her not to be superstitious,

ghosts don’t exist. First Walther and then Brausse show their whitened

faces from the flour chest and thinking that two lovers are hiding the

Miller calls for his men. But the situations are resolved and the act

ends in general happiness and reconciliation.

The score is bright, carries warm harmonies and is

fast moving. In parts the orchestration is thin as if written for a

chamber orchestra, which it probably was. The vocal lines carry enjoyable

themes, and catchy motifs are sprinkled within the orchestration: Charlotte’s

Act 1 Romance is a clear example of this fresh quality of orchestration.

Surprising is Weyse’s casting of Brausse, the formidable surgeon, as

a baritone rather than a more authoritative-sounding bass: to me the

character is too youthful whereas Saft given the voice of a bass is

rather too heavy a voice to match the feeble character. For sure, this

work has been proficiently composed. It may be worth exploring Weyse’s

symphonies to hear other likely specialities of composition of this

forgotten composer.

The soloists sing their roles with panache. Eva Hess

Thaysen and Elsebeth Dreisig sing their parts effortlessly and with

pure tone. Tina Kilberg with rich timbre does justice to her part of

Abelone. The men sing with clarity, but Gert Henning-Jensen (Walther,

baritone) needed be a little more confident at times and his thick timbre

does not always blend well in the ensemble work. In the recording the

soloists are not too forwardly placed, the sound is crisp and well balanced

so that every nuance of the score can be heard and does justice to the

excellent playing by the Danish Radio Sinfonietta.

Praise should be handed to Danish Radio for bringing

about a revival of this exciting work and recognising the importance

of their heritage of past composers. (Hopefully we in Britain will eventually

do the same rather than provide English translations of our continental

favourites. To dust down the scores of those long lost ballad operas

which Harrison and Pyne and the Carl Rosa Opera company made famous

and played to packed London theatres such as Drury Lane and Royal Italian

Opera at the Haymarket and Covent Garden would be of much interest and

greatly appreciated.)

A first class high quality 172 page booklet is included

with essay, notes and libretto in English, Danish, and German. This

includes an interesting account of the Rise of Singspiel in Denmark

around the turn of the 18th-19th Century by Jorgen Hansen. The material

helps put the listener in context with the interesting background to

this composition of Weyse.

Raymond Walker

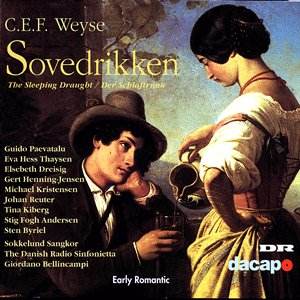

![]() Guido Paevatalu, Eva Hess

Thaysen, Elsebeth Dreisig, Gert Henning-Jensen, Michael Kristensen, Johan

Reuter, Tina Kilberg, Stig Fogh Andersen, Sten Byriel

Guido Paevatalu, Eva Hess

Thaysen, Elsebeth Dreisig, Gert Henning-Jensen, Michael Kristensen, Johan

Reuter, Tina Kilberg, Stig Fogh Andersen, Sten Byriel ![]() DA CAPO 8.224149/50

[CD1 57.51, CD2 38.35]

DA CAPO 8.224149/50

[CD1 57.51, CD2 38.35]