Rostropovich’s playing is simply stunning, and Giulini’s

accompaniments are characteristically dignified and always attentive

to his soloist’s needs. Combined, they summon up perfectly the quasi-nostalgic

sound world of this music. The London Philharmonic at the time of recording

(1977) was at a high point in its history, and how it shows. Textures

are glowing (and expertly balanced and moulded by Giulini’s expert ear)

and solo contributions are uniformly impressive: how to single out any

one is a problem. Perhaps the lyrical horn solo in the first movement

exposition, or the woodwind contributions in the second movement?.

The exact blend of musicianship present in Rostropovich

seems ideally suited to this piece. All the moments of lyrical magic

one might expect from this source are here in abundance (the slow movement

is mesmeric), but also the virtuosity displayed is jaw-dropping and

yet at once completely at the service of the music. Tempi, as in all

great performances, persuade one that they could not be otherwise (for

example, the ‘ma non troppo’ qualifier to its ‘Adagio’ is heeded so

the music flows easily and naturally). Rostropovich’s playing reaches

dizzyingly impassioned heights in the Finale. In fact, the only real

reservation about this account of the Dvorák comes with the recording

quality (David Mottley was the producer, Neville Boyling the engineer).

Despite being typical of its period in its inviting warmth (though with

a slight muddying of detail in the lower registers), there is some uncomfortable

spotlighting of solo contributions: listen to the bassoon countermelody

beginning at 6'50 in the finale, for example.

Rostropovich himself chose the Saint-Saëns as

the coupling. His love of the piece comes through strongly. Possibly

this was a controversial choice, but the piece is not without its fair

share of influential fans. Shostakovich referred to it as the best of

the ‘great’ concertos for balance, length and shape and reputedly said

he preferred it even over the Dvorák (despite its charms, I cannot

agree!). Casals was another great performer who held the piece in his

repertoire.

The Cello Concerto No. 1 was premiered in 1873 by Auguste

Tolbecque at the Societé des Concerts du Conservatoire in Paris.

Rostropovich actually made his concerto debut with this concerto at

the age of 13, so maybe that accounts for its special place in his affections.

The score is full of joy with life, from the arresting opening (a single

orchestral chord followed by an amazing flourish for soloist) through

the minuet-like Allegro con moto with its polished accompaniment over

which Rostropovich floats heavenly - this movement is delightful - to

the more shifting moods of the finale. In lesser hands, one might be

tempted to be dismissive of this concerto, but for its duration Rostropovich

refuses to let negative thoughts even enter one’s head. The coupling

of these two concertos is a remarkably successful one, and one which

makes a straight play-through of the disc a positively life-enhancing

experience.

Colin Clarke

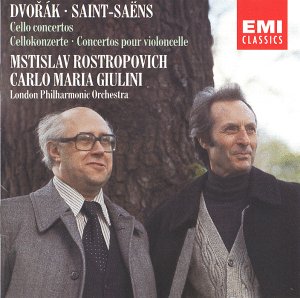

![]() Mstislav Rostropovich (cello); London Philharmonic Orchestra/Carlo Maria

Giulini.

Mstislav Rostropovich (cello); London Philharmonic Orchestra/Carlo Maria

Giulini. ![]() EMI GREAT RECORDINGS OF THE CENTURY CDM5 67593-2 [62.39]

EMI GREAT RECORDINGS OF THE CENTURY CDM5 67593-2 [62.39]