The allegretto second movement of the Seventh Symphony starts with a single chord for horns, bassoons, clarinets and oboes. Beethoven marks it to start loud, then die away until it overlaps with the entry of the strings with their restrained pulsing tune. It could be regarded as a simple 4 seconds worth of call to attention just to get things going. And that is how it sounds on most recordings.

A few years before this 1936 recording, the French conductor Louis Fourestier witnessed Toscanini rehearsing a cycle of the Beethoven symphonies in Italy. He recalled Toscanini devoting valuable rehearsal time to this one chord. "His ear for balance was exquisite. …After he had reached his goal and had achieved the diminuendo in the same gradation from each player, he said to the first oboe, 'your note - your E - make it sing! It's a melody!' ". Fourestier declared, "That was genius". This is a conductor's verdict; listeners have the opportunity to judge the result for themselves. The anecdote does, however, give us some insight into what can be special about Toscanini's performances at their best: meticulous attention to detail, almost fetishist pursuit of perfection and the conviction that music of whatever sort should "sing".

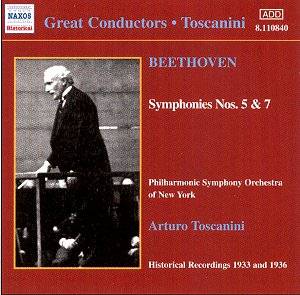

Toscanini has left us several versions of both these works recorded over four decades but here Naxos has produced a coupling that represents the conductor at the height of his powers. Made with Toscanini's own orchestra, the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York (the temporary name of the New York Philharmonic after its merger with the New York Symphony in 1928), these are, by general consent, two of the finest recordings ever made of the Fifth and Seventh, the latter having gained particular legendary status. The competition is tough. Some of the great 19th century-born conductors have left us fine performances on record: Walter, Weingartner, Furtwängler and Klemperer. Naxos has just produced the same coupling under Richard Strauss. More recent recordings of these works by Carlos Kleiber have gone into the legendary bracket, particularly the Fifth, and at 26 years old now, they will no doubt be recycled as 'historical' before long.

The above conductors represent some of the shifts in Beethoven performance over the years, matters of tempi being one of the main areas of debate. Toscanini is invariably brisker than the others and in some ways Klemperer's "hewn out of granite" architectonic approach, which usually meant going slower than anyone else, was a reaction to this. Likewise, Carlos Kleiber helped to blow away the Klemperer fashion. Now we have the original instruments movement which has coincided with a scholarly belief that many of Beethoven's metronome markings which were thought to be impossibly fast and therefore incorrect, might after all, not be so wrong.

Toscanini's performances here transcend all this. He may drive along nearly 20% faster than Klemperer in most movements but there is no less sense of the architectural whole. In fact keeping an eye on the overall design was thought of as one of Toscanini's great strengths as opposed to Furtwängler who was supposed to go for the beauty or excitement of the moment. Yet at their finest, both conductors displayed both those features. Of Furtwängler's several recordings of the Fifth Symphony up to the nineteen fifties, the one he made in 1937 with the Berlin Philharmonic provides Toscanini with his stiffest opposition. There is a double irony here. First, both conductors maintained a personal and artistic antipathy to each other. Second, a year before his 1937 recording Furtwängler was appointed Toscanini's successor at New York but had turned the post down when he realised he had rubbed too many influential people up the wrong way during his guest appearances several years earlier.

There is no doubting the greatness of these two performances of the Fifth. They have drive, excitement, moments of beauty, overall integrity and fine playing. There are some differences of approach. For example, at the arrival of the second subject in the first movement, Toscanini slows the tempo slightly and indulges some beautifully phrased lyricism, often a Furtwängleresque characteristic, while Furtwängler keeps the momentum up with no slowing, something usually thought of as a Toscanini-ism. The run up to the last movement is the biggest difference. This is one of those great moments in music, the delayed gratification of mysterious throbbings leading to the blazing rocket launch of the main subject. Toscanini's "throbbings" are quite brisk and the "launch" is decidedly emphatic when it comes whereas Furtwängler holds a little more at the run up, climaxes with a fraction more momentum and continues to wind things up steadily through the movement. Toscanini's reprise of the main subject half way through the movement maintains a tempo similar to its first appearance and his real wind up is saved for the end. For some, Furtwängler's approach tips the balance in his favour and was one of the factors that led Richard Osborne in a 1997 Radio 3 record review programme to give this "spellbinding" performance the all-time thumbs up. That view notwithstanding, anyone interested in recorded performance of this masterpiece needs both on their shelves.

In listening to these performances of such integrity it is salutary to reflect on the problems of the recording conditions at the time, everything having to be done in short takes corresponding to the side lengths of 78s. Toscanini had developed an aversion to the process and the recording of the Fifth represents RCA Victor's attempt to circumvent the problem. At a concert in Carnegie Hall on April 9th 1933 they committed the live proceedings to film sound track and this is what we hear. Four years later Victor had persuaded Toscanini to return to electrical recording under studio conditions for his famous version of the Seventh but again in the Carnegie Hall. The result was that there are two extant versions of the first third of the first movement and a major feature of this Naxos production is that both are provided (integrated into the whole movement) so you can choose. The number one take was the one first marketed but number two, prefered by Toscanini, is slightly faster and tauter. A very helpful note goes with the disc that unravels some of these technical complexities.

Toscanini's tempi in the Seventh are relatively fast and, after the introduction, the Vivace is launched slightly faster than even Beethoven's metronome instruction. However, lilt, lyricism and exquisite phrasing are not compromised and there is never a sense of rush. In the second movement, after the opening chord I referred to earlier, the music proceeds at a pace in keeping with Beethoven's allegretto marking, not the slower andante approach of many other conductors which was once thought to be authentic German tradition. Toscanini's version, though, manages to maintain a sense of glorious unfolding that many slower performance fail to achieve. The third movement Scherzo is quick, but no more than Furtwängler's 1950 Vienna Philharmonic version where the conductor reverts to stereotype with some wayward slowing and accelerating. Toscanini is steady, thrilling and maintains bounce.

The fourth movement really is Toscanini at his finest, generating a tremendous sense of the brio Beethoven asks for yet maintaining clarity of texture and melody, and a solid sense of purpose in this runaway train of a movement that could easily go off the rails. It is the music that Wagner famously described as the "apotheosis of the dance". Klemperer must have known this quote but does not heed it. In his 1960 Philharmonia recording he seems to be going for all apotheosis and no dance, plodding along at least 25% slower than Toscanini. Klemperer simply did not agree with many of Toscanini's tempi and was quite upset with the speed he took in the trio of the scherzo where Toscanini is much faster than anyone else. It should sound like an Austrian pilgrims' song said Klemperer yet there is nothing in Beethoven's indications that suggest this should be so. As a truly great conductor, Toscanini makes the music sound as if that it is how it should go and he achieved it never more so than in this wonderful performance.

John Leeman

![]() Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra

of New York/ Arturo Toscanini

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra

of New York/ Arturo Toscanini ![]() NAXOS Historical - Great

Conductors 8.110840 [c67.43]

NAXOS Historical - Great

Conductors 8.110840 [c67.43]