The Piston suite is his most famous work though

its fame is largely unmerited. It is nowhere near as fine a work as

any of the first six Piston symphonies. The Second, Third and Sixth

stand out in this company. The Flutist ballet music has glitz

and glare in spades and, to be fair, Bernstein probably gives it more

pizzazz than any other version. If the work appeals then go for it.

If you do not know it then think in terms of a confection of Satie (Relache

and Parade), Stravinsky (Pulcinella and Dumbarton

Oaks) and Berners (Triumphs of Neptune) with a dose of the

more glittering and obvious moments from Schuman's New England Pictures.

I must thank Tim Page who can always be relied on for

economical, lucid notes. He points out that Blitzstein was a

sort of mentor to Bernstein and his debt (largely unrecognised) is said

to be great. It seems fitting that the Symphony should be recorded by

Bernstein 20 years after it was written. It is a symphony only in a

similar sense to the Morning Heroes symphony of Arthur Bliss.

It is scored for narrator, tenor, baritone, chorus and orchestra (with

wind-machine). There are twelve sections, each separately banded on

this disc. The titles give some flavour of the wartime fervour of the

piece: Theory of Flight, Ballad of History and Mythology, Kittyhawk,

The Airborne, The Enemy, Threat and Approach, Ballad of the Cities,

Morning Poem, Air Force: Ballad of Hurry-Up, Night Music: Ballad of

the Bombardier, Recitative: Chorus of the Rendezvous, The Open Sky.

Welles is in young and smooth voice. He does not scorch the sky with

the hoarse volume of an Olivier. The CD booklet does not give the words

but Welles is all clarity without the lofty affectation that can settle

on the shoulders of English orators in RVW's Oxford Elegy or

the Bliss work. However texts would have been useful for the choral

and solo singer interjections. I mentioned Bliss. The history of flight

was also charted in Bliss's music for the film The Age of Flight.

I detect in Blitzstein's music the knowledge of Copland's Lincoln

Portrait also for orchestra with narrator. The Blitzstein is of

calculatedly ambitious grandeur - designed to make an occasion. It takes

something from the USA's patriotic wartime grit exemplified by Roy Harris's

Fifth Symphony. The references to the bombing of Guernica, Warsaw, Manila

and London still carry a potent charge. The choral singing recalls Vaughan

Williams' Dona Nobis Pacem and Whitman's 'immense and silent

moon'. The tableaux bind the allies together although the effect at

the first performance might well have been politically strained in a

way that would not have happened if the work had been premiered during

1945 rather than 1947. The spirit and universal bond reaches back (e.g.

in Open up that second front - track 23) to the words of John

Addington Symonds in John Ireland's These Things Shall Be and

to Randall Swingler for Britten's Ballad of Heroes and of Alan

Bush's Piano Concerto. By 1947 the US was already well down the turnpike

to realigning against such threatening universalism.

Hill, from the generation or two before Bernstein's,

represented the 'Gallic' tradition in US music. Along with Loeffler,

Farwell and Coerne, Hill tramped a quite different path from the more

Germanic Paine and Chadwick. This group was much more inclined to impressionism

and pantheistic delights. The classic late nineteenth century watercolours

of the North American wilds also played a role. Man's loneliness or

insignificance in the face of nature's vastness were wrapped into the

quite unGermanic and Delian approach. I knew the Hill Prelude from a

tape sent to me by Mark Lehman back in the 1980s. It must have been

taken from a very scrawny and distressed LP. Through all the brawling

and scratching I, even then, picked out that this was an atmospheric

companion work to Delius's In a Summer Garden, Roussel's First

Symphony and Bax's Summer Music and Enchanted Forest.

Not to be missed but very different from the other two works here. Surprising

too that this jewelled insubstantial piece dates from 1953 the very

year in which it was recorded. On this showing I would be pretty confident

that Hill's Violin Concerto and Symphonies would be worth hearing even

if his Stevensoniana suites (once available on 1960s SPAMH LPs

under Karl Krueger's direction) are unpromising. Fingers crossed that

Naxos do not run out of steam before they get to Hill in their American

Classics series. This is just the sort of piece I would have expected

Bernard Herrmann to champion and with his links as a CBS 'staffer' I

would not be surprised to see him directing performances.

A varied collection but extremely attractive and not

lacking in personality.

Rob Barnett

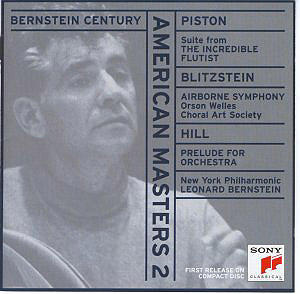

![]() cond. Leonard Bernstein

cond. Leonard Bernstein

![]() SONY CLASSICAL Bernstein

Century series SMK 61849 [78.09]

SONY CLASSICAL Bernstein

Century series SMK 61849 [78.09]