I forget which was the disc which first alerted us

to the fact that Rebecca Clarke was a composer to be reckoned with,

but I think it may have been this one. Certainly this big (even if it

lasts a mere 21’ 18" by the clock) and challenging sonata should

leave no one in any doubt. A viola-player herself she knew how to exploit

the particular tone-colours of the instrument, yet the piano part –

a truly equal partner - is no less rewarding, with its range of post-impressionist

timbres. There are more overtly French leanings than we are wont to

hear from the mainstream English composers of the time (maybe a question

of textural luminosity more than anything else), yet the cut of the

themes is definitely English. The hard-hitting scherzo is a very striking

piece, while the outer movements unite surging emotion and gentler poetry

with a firm structural hand. The two shorter pieces are also rewarding

and resourceful.

Another viola player was Frank Bridge – how violists

must regret that he never wrote a sonata to put alongside his magnificent

Cello Sonata (of which

I recently recommended a very fine recording by Oystein Birkeland

on Simax PSC 1160). The two pieces here, which are all he wrote for

his instrument, say a remarkable lot in a short space of time.

It was typical of Vaughan Williams to call a piece

a Romance, and then to write a big-boned, impassioned outpouring – and

then not even bother to publish it! About the Bax Legend I am not so

sure. Coming between the 3rd and 4th Symphonies

I would have expected something more obviously Baxian. It has fine moments

but it also reminds us that Bax, when inspiration was not forthcoming,

tended to go ahead and write anyway. The Grainger Carol arrangement

explores the viola’s lower sonorities remarkably (very remarkably

considering this wasn’t even its original form – like so much Grainger,

numerous versions abound) but the Humlet seemed to me a bit gritty for

what it’s supposed to represent. I’m afraid the 14-year-old Benjamin

Britten’s piece said nothing to me.

Finely committed performances. I did wonder about two-thirds

through if Coletti was not over-using the device of upward portamenti

which, together with a strong and fast vibrato, create a gypsy-style

effect at times. But this is a matter of personal taste and there is

no doubt he’s an excellent player and works well in duo with Howard.

The recording seemed a bit close in the two solo pieces but this is

a marginal quibble and some might prefer it like that.

All in all, the record serves to show that, thanks

to Lionel Tertis’s inspiration, Great Britain probably produced a larger

20th Century viola repertoire than any other country, and

there must be much more to discover. I remember working at a fine sonata

by Thomas Pitfield in my schooldays with a viola-playing friend, for

example, and would rather like to hear it again. And, since another

point of this CD is the rediscovery of a splendid woman-composer, could

I point out that Dorothy Howell might equally repay examination? Don’t

think I have a personal interest, she was no relation of mine; but some

of her shorter piano pieces that I have seen are decidedly impressive.

Christopher Howell

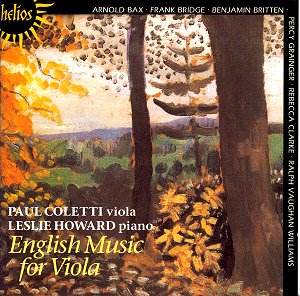

![]() Paul Coletti (viola), Leslie

Howard (pianoforte)

Paul Coletti (viola), Leslie

Howard (pianoforte) ![]() HYPERION HELIOS CDH55085

[66.51] Budget price

HYPERION HELIOS CDH55085

[66.51] Budget price