In the days of vinyl the Westminster label, coupled

to Britain’s Nixa records in the 1950s, became not only familiar but

also a force to be reckoned with. At the start its star conductor was

the German, Hermann Scherchen, though their stable of solo artists included

such distinguished names as Paul Badura-Skoda and Jean Fournier. With

the development of stereo sound in 1956 the catalogue began to broaden

with even greater names such as Rodzinski, Leinsdorf, Abravanel, Knappertsbusch,

Barenboim, Peerce, Stich-Randall, Forrester, Sills and Monteux. They

used the single microphone ‘natural balance’ recording technique and

their best work is now being reproduced on CD.

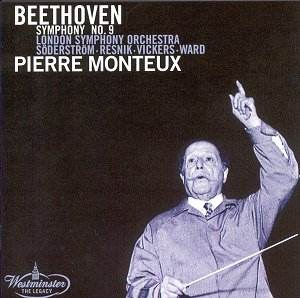

Pierre Monteux (1875-1964) was 87 when he made this

recording. He was a diminutive figure, corpulent with a Colonel Blimpish

appearance dominated by his bushy moustache, looking rather like a French

version of the British comedian Jimmy Edwards. Like his contemporary

colleagues Stokowski and Klemperer, and like Günter Wand today,

he was enjoying an Indian summer of a career while in his eighties (he

had just two more years to live). He started his childhood studies as

a violinist and his career as an orchestral player, and as a conductor

it was his appointment as conductor of Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes and

its association with Stravinsky’s music which launched him. The 1913

scandalous succès d’estime of the Rite of Spring

in Paris is well documented, then he worked with Debussy and Ravel to

create their new works, such as Jeux and Daphnis

et Chloë respectively. After a couple of years at the Met

in New York (1917-1919) he took on the union-troubled Boston Symphony

Orchestra for a while, and then in 1936 the San Francisco Symphony,

becoming a US citizen in 1942. In 1961, at the age of 86 and demanding

a 25 year-contract with the option of renewal, he was unanimously appointed

chief conductor of the LSO, with whom he works on this disc and who

clearly play their hearts out for him. His platform manner was unostentatious

yet authoritative, for he had a phenomenal ear and, though not an orchestral

trainer, he had one of the widest repertoires in the profession.

This is a revelatory performance of the Choral

symphony. It may not be entirely unblemished but there is lightness

of touch, transparency of texture, and some fine individual playing

from members of the orchestra as well as excellent singing from the

distinguished cast of singers and chorus in the finale. There’s no hint

of stodginess in Monteux’s widely varied choice of tempi, a striking

feature from the very outset. There is a point about eight minutes into

the Adagio where the music can meander and drift shapelessly as it fragments

into various solos taken around the orchestra (always a deathtrap moment

in the theme and variation principle) but Monteux avoids it cleverly

by a driving speed which nevertheless retains the space this music needs

for all the ‘small’ notes. In the famous finale the recording balance

is somewhat destabilised with all the singers rather distant, but on

the other hand a lot orchestral detail emerges, which is often obscured.

The tempi for the finale are on the steady side but Monteux gives it

all a sense of dignified, stately progression (Vickers strains at the

leash at ‘Jauchzet, Brüder’). The chorus provide a full-bodied

texture, just a hint of strain in the sopranos in the final stretches

(‘Sei willkommen Millionen’), the tenors (following their solo kinsman)

try to rush away (‘Such ihn über’m Sternenzelt’), the words as

clear as one can reasonably expect in this almost unsingable work. The

coda is thrillingly fast and conducted with the youthful exuberance

of a man sixty years his junior. If you don’t know this recording, you

should.

Christopher Fifield

Pierre Monteux, conductor

Pierre Monteux, conductor