Walter Gieseking (1895-1956) is especially remembered

for his interpretations of Ravel and, above all, of Debussy (his celebrated

recordings of that composer’s Préludes have already been reissued

in this series). However, he was also a gifted interpreter of the classical

repertoire and this reminder of his prowess in Beethoven is timely and

welcome.

As Bryce Morrison points out in his excellent accompanying

note, Gieseking recorded 23 of the Beethoven sonatas for HMV and he

suggests that the four collected on this disc are among the best. Gieseking

was never given much to technical practice. He was more of an ‘instinctive’

player (albeit one blessed with a superb technique) and so his performances

contain occasional fluffs or passages of slightly blurred fingerwork.

In my view these matter not one jot. As with Schnabel, though in a very

different style, Gieseking always convinces the listener that he has

penetrated to the heart of the music (as he sees it) and he conveys

his vision marvellously.

Morrison describes Gieseking’s performance of the first

movement of Op. 53 as "fleet and mysterious", a most apt description.

Schnabel (his 1933 recording) is similarly fleet but a touch more forthright

while Brendel (in 1973) is more direct than either. Personally, I’m

just glad there is such a wonderful choice available! In Gieseking’s

hands the slow movement of the ‘Waldstein’ has a wonderfully rapt quality

which just removes the desire to make comparisons. One is under the

spell completely as, in fact, is the case in all the slow movements

on this disc. There is a wonderful poise to the opening of the finale

but Gieseking can call on appropriate reserves of power later in the

movement (is Brendel perhaps a little too broad in this movement?)

The wonderful account of Op. 53 is followed by an equally

fine traversal of Op. 57. The first movement opens with a magical air

of suspense, and if the early downward torrent of notes (track 4, 0’.

35") sounds a little smudged one readily overlooks such tiny blemishes

since the overall conception is so convincing. Another serene, humane

slow movement follows, though I find that Brendel (1970) weights each

chord with much more subtle differentiation. Both have the requisite

fire and passion in the finale. Gieseking’s touch is a little lighter

but that’s his essential style and his approach is no less apt than

Brendel’s.

I also very much enjoyed Gieseking’ performance of

Op. 109. Here, the weight of the argument falls on the third movement,

a theme and six variations. Gieseking handles this movement beautifully,

with superb poise evident, for example, in the simple statement of the

theme. I think his view of this movement is to be preferred to Schnabel’s

(in 1942). Schnabel takes over three minutes longer for this movement.

Overall Gieseking strikes me as being less extreme without sacrificing

any depth.

To complete the set we get Op 110. I‘ve used the word

"poise" several times already in this review and it’s apt

for this performance too. This is not to suggest that strength is absent:

the second movement is delivered with just the right degree of energy.

However, it’s the serenity in the finale which I find particularly satisfying.

The prevailing mood of this movement is an Olympian calm and Gieseking

finds just the right degree of innigkeit. Bryce Morrison rightly

draws attention to the final L’istesso tempo section. Gieseking

makes it fall like a benediction.

Morrison says that Gieseking "tacitly forbids

all comparisons". I know what he means though I’ve dared to make

some. However, the few that I have made do not, I think, find Gieseking

wanting. His is by no means the only way of playing Beethoven but when

one hears it one is persuaded that it’s a very compelling way.

The mono sound is satisfactory though, perhaps inevitably,

there’s some clanging in the piano tone in the upper registers. However,

any sonic limitations do not impede enjoyment of a most distinguished

recital. Strongly recommended.

John Quinn

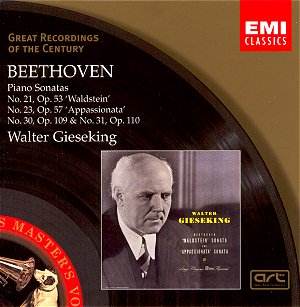

![]() Walter Gieseking (piano)

Walter Gieseking (piano)

![]() EMI GREAT RECORDINGS

OF THE CENTURY CDM 5 67585 2 0 [79.29]

EMI GREAT RECORDINGS

OF THE CENTURY CDM 5 67585 2 0 [79.29]