This new Naxos release is another of the 'Great Violinists'

archive recordings, but the series title is in this case something of

a misnomer, as it unjustly ignores the fine pianist Rudolf Serkin (1903-1991).

Serkin, himself a fine soloist and chamber musician, is just as important

as his colleague in this violin and piano partnership, which is regarded

as one of the great string duos of the 20th century. The association

between Serkin and Busch originated from Busch’s large circles of chamber

music players (including the Busch Quartet), and it was through these

meetings that a permanent working arrangement with Serkin eventually

arose. At first, the partnership seemed unlikely - Busch, at 29, was

already widely regarded in musical society, and was a disciple of Joachim’s

musical pedagogy. Serkin on the other hand, was a tender 17 year old,

highly influenced by the avant-garde second Viennese School. Despite

these differences, a strong artistic bond was soon formed, and Serkin

became as close as a son to Busch and his wife - he even married Adolf's

daughter, Irene Busch! One of the key factors in the duo’s success was

Busch's underlying belief that sonatas for violin and piano were essentially

duos, and that the pianist should never suffer any musical discrimination.

The consequence of this dualistic approach is a performance

of enormous musical integrity. Each of the two men is entirely aware

of the other’s nuances and phrasing, and their intimate understanding

of one another’s ideas leads to some sublime moments of delicacy in

the Adagio movements of the sonatas, and some delicious interplay elsewhere

– the Spring Sonata’s Scherzo and Trio and the Rondo

of Sonata No.3 for instance, are vigorous and spirited interpretations.

The playful interaction of the violin and piano sounds as natural as

human conversation, yet a balanced, thoughtful approach is always in

evidence – the performance is always tasteful and, even behind the element

of risk which is part of every live performance, there is a feeling

of musical security that can only arise from a real and absolute understanding

of the music.

The reason for the recording’s reissue is of course

the historical perspective on Busch’s violin-playing, and his overall

sound is very interesting to hear. The tone is intense and powerful

– even in moments of tenderness he maintains an unusually clear body

to the sound – and there is a slight edge to his playing which, far

from being off-putting, actually adds clarity. Another consequence of

this is that many of Busch’s individual notes begin with the percussiveness

of a piano, adding to the integration of the two artists even further.

Mark Obert-Thorn’s transfer from 78 to CD – described by him as a ‘moderate

intervention’ rather than a complete re-processing – is exemplary; in

allowing the original idiosyncrasies of the analogue recording to come

through, he maintains the authenticity of the original discs.

The CD comes complete with Tully Potter's excellent

sleeve notes, and is yet another example of Naxos' uncompromising balance

between quality and commercial pre-eminence. An outstanding release.

Simon Hewitt Jones

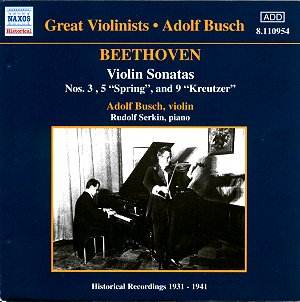

![]() Adolf Busch (violin)

Adolf Busch (violin) ![]() NAXOS 8.110954 [65.04]

NAXOS 8.110954 [65.04]