Both the symphonies were, of course, staples of Toscaniniís

repertoire. He had recorded the fourth movement of No. 5 during his

first recording sessions, in 1920, on tour with the La Scala Orchestra.

However it wasnít until RCA Victor sought ways around his frustration

with the technical limitations of sound reproduction that Toscaniniís

recording career began in earnest.

This 1933 recording of the Fifth Symphony was the second

attempt to capture his interpretation Ė the 1931 optical film recording

was never approved for release at the time; Naxos will be bringing out

their transfer of that in the fifth volume of their laudable series

of reissues devoted to all the Philharmonic- Symphony recordings. Similarly

the Seventh had already been captured with the BBC Symphony Orchestra,

available with other superb Queenís Hall performances on BBCL40162

when, the following year, 1936, Victor employed a two-turntable

system to record the symphony, to Toscaniniís satisfaction.

The vagaries and complexities of the several attempts

to record Toscaniniís Beethoven, whilst never as labyrinthine as those

of his supposed antipode, Furtwängler, (provenance, dating, questions

of attribution) nevertheless presents the listener with complicated

choices. Toscaniniís 1930s readings are lyrically superior to

the later NBC discs; they are freer in tempo and richer in phrasing.

Orchestral sonorities are broader and deeper. That said the 1931 recording

of the Fifth is preferable to this 1933 traversal, powerful and direct

though the latter undoubtedly is. The Seventh has tremendous reserves

of expressive power and the rhythmic attack is of galvanizing intensity

to a degree remarkable even for Toscanini. The orchestra was an instrument

capable of optimum flexibility and virtuosity. It is a remarkable document.

Naxos, in common with their policy to release all the

Toscanini/Philharmonic-Symphony discs, includes two takes of the first

movement of the Seventh Symphony. Toscanini watchers can note the difference

of 23 secondsí duration between them and draw appropriate conclusions.

The sound is generally fine on these discs, the restoration is by Mark

Obert-Thorn, and notes cover the discographical matters with comprehensive

zeal.

Jonathan Woolf

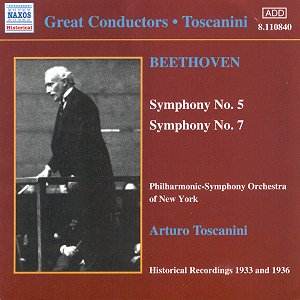

![]() Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra

of New York

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra

of New York ![]() NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.110840

[76.46]

NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.110840

[76.46]