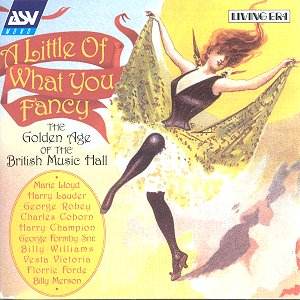

"A LITTLE OF WHAT YOU FANCY"

The Golden Age of the British Music Hall: Recordings from

1901-1931

Marie Lloyd, Harry

Lauder, George Robey, Charles Coborn, Harry Champion, George Formby Snr.,

Billy Williams, Vesta Victoria, Florrie Forde, Billy Merson.Will Fyffe, Dan

Leno, Little Tich, Albert Whelan, Gus Elen, Norah Blaney, Lily Morris, Vesta

Tilley, Albert Chevalier, Billy Williams. Marie Lloyd, Harry

Lauder, George Robey, Charles Coborn, Harry Champion, George Formby Snr.,

Billy Williams, Vesta Victoria, Florrie Forde, Billy Merson.Will Fyffe, Dan

Leno, Little Tich, Albert Whelan, Gus Elen, Norah Blaney, Lily Morris, Vesta

Tilley, Albert Chevalier, Billy Williams.

ASV Living Era CD

AJA 5363

[74.56] ASV Living Era CD

AJA 5363

[74.56]

Crotchet

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Amazon

recommendations |

|

"Lost Empires" was the title J.B. Priestley gave to the second of his two

novels set in the world of the Edwardian music hall. It was written in old

age when nostalgia had had the chance to throw what he could remember into

some kind of context and give it meaning beyond that which the he had first

perceived and written about in "The Good Companions". Many great theatres

of the Victorian and Edwardian Music Hall had the word Empire in their titles

and Priestley clearly played on the fact that with the theatrical

empires the larger world of the British Empire that surrounded them

went too. For him these theatres represented a microcosm of social life,

particularly in the years leading up to the Great War in 1914. All classes

came to be entertained under the same roofs and yet a fierce segregation

based on money took place inside - in order of precedence: gods, stalls,

gallery, circle and boxes - though it was one that the great performers

of the time were able to play on, maybe unconsciously, and which, with benefit

of hindsight ,Priestley recognised. We too can also observe it a little by

the pinhole glimpses the recordings that have survived of the artistes give

us, some of which are contained on this disc. I would quibble a little with

the idea that this was the golden age, though. The real golden age

was probably in the 1870s when in London there were around three hundred

music halls, most of them part of taverns and pubs and which, for a short

time, co-existed with the larger palaces of variety which would eventually

win out. After 1878 profound changes in various licensing laws led to a rapid

decline in the numbers of the smaller, genuine music halls where you could

drink and watch the acts at the same time. Gradually the talent then moved

over to the variety theatres which came to be owned by large management companies

and families - Stoll, Moss, Thornton, Gibbons etc. Though this probably enlarged

their audience to take in the new urban middle classes and also legitimatise

the presence of the upper classes who until then had had to go "slumming"

if they were to see the kind of entertainment they really should have stayed

away from. After the Great War the Music Hall came more under the influence

of American Vaudeville and early cinema so real Variety was born. But many

of the manners and mores of the old music halls were carried forward in the

singers and comedians of the 1920s and 1930s along with some of the variety

theatres that themselves would last until after the Second World War. If

Hitler's bombs didn't flatten them they were later turned into Bingo halls

or cinemas or car parks. But the original Music Hall, the one that came out

of the rooms with the pubs to conquer the West End of London and many of

the larger cities around the nation too, was gone and the world it represented

went with it, as Priestley later recognised.

There is perhaps another reason why this period retains a special nostalgic

appeal even to those who were never there. These long golden and silver ages

were over before technology could catch up and truly record it for us so

recordings like the ones on this CD were all made in unatmospheric studios

with no audience present. For performers to whom the thrill of a full house

was essential this must have been torture. So we are never really hearing

them at their best, playing to the gallery. This alongside the fact that

the three or four minutes allowed by early acoustic recordings places further

restriction on them. So there is much that has to be filled in by the imagination

and imagination is the most potent element of all in nostalgia. This should

awaken a small note of caution to be on our guard not to read too much into

what we hear, though. These are still entertainers pure and simple and would

have been perceived as such by their audiences. Many of the recordings contained

on this disc certainly date from the relevant time before the Great War but

a handful are made later in careers when the artistes concerned were past

their best. However, I think there is still more than enough for us to glimpse

and imagine what it might have been like to sit in the stalls or gods (or

the gallery if we could afford it) and be entertained. For there is no denying

the thrill of hearing a performer singing his or her hit song on an afternoon

or morning in 1905 or 1910 prior to going onstage in the evening and doing

it again. There are some films of old performers but these were mostly made

in the 1930s in film studios for inclusion in cinema programmes between the

main movie and the Newsreel. By then the performers - Gus Elen, Lily Morris,

George Robey and Charles Coborn among them - were old and grey and again

had no audience they could see. It only remains to say that Marten Haskell's

remastering of these precious documents is exemplary with sound from, in

some cases, a century ago sounding clearer than we have any rights to hope.

There are times when the voices of those distant shadows down in the smoky

limelight seem to be in the room with us.

The best known and loved performer of the Victorian and Edwardian Music Hall

was Marie Lloyd. A genuine East End Cockney born in Hoxton, like a number

of music hall artistes, her stock-in-trade was a cheeky double meaning and

a frowzy glamour aimed at both the working classes in the stalls and the

toffs in the circle. The former could see her aping and sending up the latter,

the latter could get a cheap thrill from seeing one the former aspiring to

"better" things and alluding to matters no lady of their acquaintance

would ever do. Many of the men might encounter ladies of the night who came

close, but that was not to be admitted. When Marie was onstage both sets

of customers could chuckle at matters that publicly neither was meant to

know anything about at all, but since it was Marie it was permitted to do

so. Rather like Max Miller's blue and white joke books thirty years later,

where he would give the audience the choice of clean or smutty material,

they were licensed to laugh at bodily functions and carnal urges. In fact

she had the kind of gentle British vulgarity that would endure into our own

time in Benny Hill and the "Carry On" films. There were problems over the

years, of course. Marie's once had a song about gardening called "I Sits

Among My Cabbages and Peas" but when the Lord Chamberlain, effectively

the theatre censor, saw the words he was outraged. Such vulgarity would not

be allowed, she was told by his office. Quick as a flash, Marie changed the

words and the song became "I Sits Among My Cabbages and Leaks". The

Lord Chamberlain's blushes were spared, the crowd roared and Marie Lloyd

marched on. Soon she reverted to the original, of course. There are two songs

from Marie Lloyd on this disc. From 1912 in "When I Take My Morning

Promenade" she is in "lady of quality" mode. But this is a lady of quality

with enough Edwardian equivalent "trailer park trash" to know the cut of

the new dress is there to turn the boys on and to admit the fact in public.

How shocking, how alluring and how it must have tickled the stage door Johnnies

in the gallery as well as giving the factory girls in the gods some hope.

"I don't mind nice boys staring hard if it satisfies their desires" she sings

shamelessly. How they loved it when she talked dirty. Then from 1916 we have

one of her best known songs and this CD's title track, "A Little of What

You Fancy Does You Good." Here she's Marie Lloyd the Hoxton working girl

(in more ways than one) and also, it must be said, one who has by then seen

better days. She was only forty-two when she recorded this, but the years,

and her last husband, were not treating her well by then. Within ten years

she would collapse in the wings and die soon after. So her life was a short

but gay one, "a candle in the wind" burned at both ends and up the sides

as well. For all her background, notice her impeccable diction, every word

clear, every stress and emphasis the product of years of practice onstage

and in the last verse where she sings "A little of what you fancy doos

you good" there is even an echo of her cockney origins. On this disc is also

another of Marie's best-known songs but, for some reason, it's sung here

by Norah Blaney in 1931. It's "Oh Mr. Porter" which also fell foul

of the censor with the original line "I've never 'ad me ticket punched before"

proving too much for Edwardian sensibilities. One of the greatest of all

Edwardians, though Marie was excluded from two Royal Command Performances

owing to her domestic arrangements, she was beloved of Royalty and, in spite

of contemporary hypocrisy preventing their showing it publicly, probably

had friends in high places that saved her from more serious trouble.

Marie Lloyd once said there were only two acts she would willingly watch

from the wings and they were Dan Leno and George Formby. But this, of course,

was George Formby Senior. Because the biggest British male star of

the 1940s had a father, also called George, who before the Great War was

just as famous as his son and so earns his place on this disc. The old man's

stock in trade often sounds like an older version of the son, but it was

more than that. Formby Senior was perhaps the first of the northern comics

who confirmed the stereotype that everyone north of Watford was a slow-witted

idiot. One of his first manifestations in the halls down south was "John

Willie", up in London for the cup, with tales of Wigan Pier which Formby,

let it be remembered, invented. In the eyes of Londoners it's doubtful the

reputations of the citizens of Lancashire and Yorkshire have ever recovered

from what he started, in fact. Formby was never a well man either. His lungs

bore the marks of consumption from breathing in sulphur when as a boy he

worked in a Manchester steel foundry and his trademark cough was as famous

in its day as his son's ukulele would become thirty years later. Indeed George

would often break off in the middle of a song to have a good hearty cough

("coughing better tonight - coughing summat champion") and have the customers

rolling in the aisles. So on stage he was both simple and always ailing,

and frequently complaining. There is one song here from Formby Senior and

it's a cracker recorded in 1916. He rewrites the words to the old favourite

"My Grandfather's Clock" and turns in a classic Lancashire monologue

with references to coal holes, grandparents refusing to die when they are

supposed to and excess children wheeled around in makeshift prams. A rich

slice of pre-Great War working class life served up with a dollop of whinge

(and a stick-on star for those who can spot the reference to the game of

Dominoes). As with Marie Lloyd taking on the persona of the "lady of quality",

here was a window into a world many of the audiences in the stalls and boxes

in London would never have seen before. That was when Formby chose to come

south, of course. The Lost Empires of the north were really all he ever needed

and stayed in them a lot of the time. Just as with Marie Lloyd every word

is clear, every inflection perfect and there is also comic timing "to die

for". "Them that doesn't want to listen, get out 't room, please, because

it's only an annoyance to me," George complains wheezily. Poor George. It

was only being so cheerful that kept him going, as another northern comedian

was fond of maintaining. The cough got to him in the end, of course. One

night in 1921, on stage at the Newcastle Empire, he coughed too hard, burst

a blood vessel and expired. A fellow northern comedian of Formby's was Billy

Merson. Though born in Nottingham, that was Northern enough for those down

in London. Merson sings that old favourite "The Spaniard That Blighted

My Life" recorded in 1911. And why shouldn't he? He wrote the song after

all and so tapped into the native suspicion of his audiences in all parts

of the theatre that foreigners were "dirty dogs" not to be trusted. If you

have ever heard the version by Bing Crosby and Al Jolson then you need to

hear the original, believe me. Especially with the yodelling at the end.

Yodelling at a bullfight? Why not?

Time to bring in some more ladies. Lily Morris gives us "Only A Working

Man" from 1927. Better known would have been "Why Am I Always The

Bridesmaid?" or "Don't Have Any More Mrs. Moore", but there is

black humour in the story of the woman who goes out to work to support her

layabout husband and still loves him for all that. Marriage is also on the

mind of Vesta Victoria in her best-known song "Waiting At The Church"

recorded late again in a long career in 1931 and so losing some of the magic

it must have had when first performed. Then there's Florrie Forde who they

sometimes called "The Australian Marie Lloyd", though never in the hearing

of the great lady herself, of course. Here we have Florrie from 1905 singing

one of her greatest hits "Down At The Old Bull and Bush". You may

know this song from the close of every edition of "The Good Old Days"

on BBC TV. However, that splendid old series bore little relationship to

the genuine Victorian and Edwardian music hall and the same can be said of

how the show perpetuated the way this song should be sung. Florrie Forde

reminds us it's a much more lyrical song that a slightly slower delivery

brings. Listening straight after to her in "Has Anybody Here Seen

Kelly?" also on this disc and recorded in 1909 reminds us again what

great singers so many of these artistes were. Not just the clarity of her

diction, but the phrasing and breathing is the product of a singer for whom

the microphone was unnecessary and who knew the only way to make herself

heard at the back was to sing as well as she could. The song also contains

a reference back to one of her other well-loved songs "Oh Oh Antonio"

which those in her audience would already be familiar and her many fans would

nod in sympathetic recognition. They knew the poor girl had already been

dumped by a sweet-talking Italian with hot blood and a cold iced cream van.

Now a bounder from the Isle of Man had done the dirty. In the Great War Florrie

would belt out "Pack Up Your Troubles", "Take Me Back To Dear Old

Blighty" and many more for the troops, beating time with a jewelled cane

as she strutted her stuff. A buxom lady, given to feathers, she must have

been worth a battleship or two to the war effort.

There are two other Australians

represented here, Albert Whelan and Billy

Williams. Billy Williams delivers a really

irritating version of "When Father Papered

The Parlour" from 1911 with forced laughter

trying to project the "hail fellow well met"

image he tried to make his own. He also used

to sing a song called "John, John, Go and

Put Your Trousers On". (No, don't ask.)

With Albert Whelan the influence of American

Vaudeville can be heard in "The Preacher

and The Bear" where he takes a shot at

an American accent and misses by miles. But

this was one of the later electric recordings

from 1931 so by then the Golden Age had passed.

But it's still fun to hear Albert working

as much as he can into the four minutes he

gets - cod American preacher, animal impersonator,

whistler, and a bit of drama. Because Albert

started life as an actor and you have the

feeling he never quite got over the shame

of having to leave it all behind him, reflected

in the image of the debonair man-about-town

he took on. Mentioning American influence

also brings me to the delicate issue of performers

who would "black up" to mimic the American

Minstrel shows that came to England from time

to time. Politically incorrect to even speak

of now, but it has to be remembered there

were such acts as G.H. Elliot "The Chocolate-Coloured

Coon" and even one troop of singers who actually

went on the bill as "The Gay White Coons".

Here we have the New York born Eugene Stratton

who was often styled "The Dandy Coon" or "The

Whistling Coon" when he blacked his face.

His stylish rendition of "The Lily of Laguna"

from 1911 brings one of the most loved songs

of the day in an impeccable performance, reminding

us that the Music Halls weren't all laughs,

jokes, men with black faces, men dressed up

as women and women dressed up as men. To whom

we now must turn.

The best known of the male impersonators was Vesta Tilley whose performances

before and during the Great War earned her the nickname, as Peter Dempsey

points out in his notes, of "England's Greatest Recruiting Sergeant".

"Jolly Good Luck To The Girl Who Loves A Soldier" represents her here

and it was recorded in 1915, with Albert Ketelbey conducting, whilst the

men were going "over the top" in France and Vesta was doing much the same

in the halls, as you can hear. It has about it the same air of gentle

pressure that "We Don't Want To Lose You But We think You Ought

to Go" would have brought on a generation about to go to hell. You can

only speculate the real effect it had on the young men and girls who heard

it. Social document again, you see. It is a pity Peter Dempsey's notes do

make the same mistake a lot of people make regarding the greatest of all

male impersonator's songs, however. The one I mean, of course, is

"Burlington Bertie From Bow." Dempsey tells us in his notes that Vesta

Tilley sang it, but that on this CD Ella Shields sings it instead.

In fact the song about Burlington Bertie that Vesta Tilley used to sing was

an altogether different one ("Burlington Bertie - the boy with the Hyde Park

drawl") and, though similar in tone, is now largely forgotten. The more famous

song, always sung by Ella Shields, was actually written especially for her

by her husband William Hargreaves (who also wrote "My Grandfather's

Clock") and she made it her own, probably to Vesta's dismay. However,

Vesta was the pre-eminent male impersonator perhaps challenged only by Hetty

King.

Ella Shields was American by birth and recorded "Burlington Bertie From

Bow" a number of times. The version here dates from 1916 and contains

one verse not included in her first recording from 1915. However, that contains

a verse not included here, as all the verses would never fit on to one 78rpm

side. This wonderful song, in my view one of the finest popular songs ever

written in England, still retains its ability to evoke the past and open

another window on a world now gone with specific references to personalities

known to everyone then. Tom Lipton the grocer and tea importer, Lord Roseberry

the Foreign Secretary, F.E. Smith who was Lord Birkenhead, Lord Derby of

equestrian fame, Rothschild the banker, The Prince of Wales. Most famous

of all there is the experience of having "had a banana with Lady Diana" which

brings in Lady Diana Manners, the most beautiful girl in pre-Great War London.

In time this original "It" girl would marry a young politician called Duff

Cooper and go down in history as Lady Diana Cooper. More than all that, though,

Ella's portrayal of the working class boy putting on the airs and graces

of the toffs and convincing them he was what he claimed cocked the kind of

snook the inhabitants of the stalls would have loved, which is why such songs

were popular. There were other songs with the same theme, but this was the

best. What the toffs upstairs thought we can only speculate, but we certainly

have here another document of social history. It's a curious coincidence

that Vesta Tilley and Ella Shields both died in the same year, 1952. Vesta

hadn't appeared on stage since 1920 after marrying one of the large theatre

owners, but Ella played to audiences up to her death, breathing her last

in a dressing room in Morecambe at the age of seventy-three. Legend has it

that in her last rendition of her most famous song, instead of opening with

"I'm Bert," she told her audience "I was Bert". Nice thought, probably

not true, but I think it should be. Much more to the taste of the men in

the top hats upstairs would be Charles Coborn's "The Man Who Broke The

Bank At Monte Carlo", based on the true story of Charles de Ville Wells,

which Coborn performed as early as 1891. Here he recorded it when he was

an old man in 1929, but you can still get a whiff of the cigar smoke from

himself and his admirers, I think. The song made Coborn's fortune as he had

bought it from its author for twenty pounds early in his career.

One star who was perhaps the male equivalent in terms of fame as Marie Lloyd

was the comedian George Robey, "The Prime Minister of Mirth", who also had

the distinction of being the first music hall star to be knighted. Today

his humour seems a little too fey and whimsical, but in his day George would

pack theatres out with his various characters that included a matchless pantomime

dame. In 1916 he starred at the Alhambra Theatre with Violet Lorraine in

the revue "The Bing Boys Are Here" where he played Lucifer Bing and

entertained, night after night through that long hot Summer, the men about

to cross to France to be ground through the mincer of the Battle of the Somme

that began in the July. It is said that after the shows the young subalterns

would walk into Trafalgar Square at midnight where, in the silence, they

could hear the guns of the initial bombardment all the way across the channel.

The hit song from that show was "If You Were The Only Girl In The World"

which he and Violet Lorraine recorded in the run. Alas, that evocative recording

is not on this disc, but we have instead the less well-known "Quite

Alright" which is still a good illustration of Robey's slightly

school-masterish, rather "hammy" manner. A little like the better known "I

Stopped and I Looked and I Listened", which he filmed in the 1930s leaving

the best known image of him in bowler hat, clerical coat and large eyebrows.

There are other comedians on this disc. Three Londoners, distinctive cockney

"Coster Comedians" who would charm the nobs upstairs with another portal

into what they thought was the world of the poor and make the proles in the

stalls feel at home. The best known was Gus Elen. He was born in Pimlico,

not Ramsgate as Peter Dempsey maintains in his notes, and began as a street

busker with a barrel organ in the Strand in the 1880s. Gus became one of

the biggest stars of the Victorian and Edwardian Music Halls who made a lot

of money and retired just before the Great War when he was fifty-two and

so came out of the true Golden Age. But he was lured from retirement in 1931

for a Royal Variety Performance at the London Palladium where he received

a standing ovation and it's from this time all his sound recordings date,

as well as a couple of filmed renditions. On this record we have "If It

Wasn't For The 'Ouses In Between" bemoaning the lot of those who endured

crowded housing as the urban classes expanded. Listen to his particular

pronunciation too. Here is the real, original Victorian cockney dialect,

now long gone and replaced with Estuary English. But perhaps the greatest

of all the "Costers" was "The Kipling of The Music Hall", Albert Chevalier.

Albert wrote his own material and left us "Knocked 'Em In The Old Kent

Road" among many. On this disc we have perhaps his best known song, the

sentimental "My Old Dutch" recorded in 1911. What the people in the

halls would know and which we today might not was that this song has a vein

of real tragedy buried in it. What might seem simply a tribute from an old

man to his much loved wife for forty years was inspired by the fact that

when the old could care for themselves no longer it meant the workhouse where,

you've guessed, they are separated. Listen to the song again with that in

your mind and it takes on a completely different complexion. Perhaps Albert

was more mawkish than his great rival Elen whose view of life retained more

irony, but there is no doubt he was a man of enormous talent. For the last

of the three "Costers" we come to Harry Champion, an almost exact contemporary

of Gus Elen's. Like both Elen and Chevalier he went through a phase early

in his career "blacked up" as a "Coon" comedian. In his prime Harry sang

in what might best be described as a controlled apoplexy. The feeling that

at the end of each number the stage hands had to dash on from the wings,

throw a tarpaulin over him and peg him down. In "Any Old Iron" recorded

in 1911 the orchestra manages to hang on, but it's a toss-up who gets to

the end first: Harry, the orchestra, or the demon trumpeter who doesn't so

much as blow into his instrument as bite on it. By the time Harry recorded

"I'm Henery The Eighth I Am" twenty years have passed, electric recording

has come in and a few thousand Woodbines have clinkered up the Champion vocal

chords. But he still manages to belt out the old favourite shorn of a verse

or two, probably to save his blood pressure. There is in existence an earlier

recording by him of the whole song, by the way. Another of the "past their

best" recordings here but a gem, even though it's slightly unrepresentative

in that most of Harry's songs were about food - "Boiled Beef and Carrots"

and "I Like Pickled Onions" etc.

There are two other comedians from an earlier era on this disc - Dan Leno

and Little Tich. Dan Leno is a legendary figure in show business history.

Perhaps because he died young in 1901. But there is no denying he was a massive

star in the later 19th century, on a par with Marie Lloyd who

was a great admirer. He was also more of a character comedian than the "Costers"

and a pantomime dame too who played the Theatre Royal Drury Lane for fifteen

seasons starting in 1888. Often appearing there with Marie Lloyd and Little

Tich. Alas there is little left of Dan Leno on record. I do know of "The

Tower of London" where he played a Beefeater, but here we have "The

May Day Fireman". Time has not been kind to what has survived of Dan

Leno's humour, it must be admitted. It was mainly monologues with a surreal

propensity to go off at tangents. You clearly had to "be there" and it's

said he could bring the house down with a look. But to hear him recorded

here in 1901 (the oldest recording on this disc) is still special. There

is also a side interest in Leno's piano accompanist here. It's none other

than the young Fred Gaisberg who would later go on to be the top classical

record producer of the 1930s working with, among others, Bruno Walter with

whom he made the first gramophone recordings of Mahler's last completed works.

A year or so after playing the piano for Dan Leno, Gaisberg would go to Rome

and make records with the last genuine castrato in the Vatican Choir

as well as record the voice of Pope Leo XIII, a man born before the Battle

of Waterloo. Gaisberg was a man who clearly saw some history and put it on

record for us. Almost as famous as Dan Leno, Little Tich was the diminutive

entertainer who you may have seen in a very grainy contemporary French film

performing his famous giant shoe routine. However, Little Tich was also a

comedian of the same stature as Dan Leno and here we can hear him in his

"droll" Gas Inspector routine recorded in 1911. As with Dan Leno there is

a verse or two of song to introduce himself, then the monologue, then another

verse to finish. Notice how he fluffs his lines halfway through and has to

carry on. No retakes, you see. Wax discs were expensive and he was probably

warned to keep going.

The two great Scots comedians Harry Lauder and Will Fyffe graduated from

that graveyard of English comics, The Glasgow Empire. It's said they had

more intervals in the shows in Glasgow so that the audiences could

reload. Many were the comedians from south of the border, sick with

nerves, who would retreat to the wings with shouts of "Away hame and bile

yer heed" from the stalls. However, it must be the case that when they came

south Harry and Will accentuated the Englishman's idea of the Scotsman to

the extent that today few Scottish comedians would claim ancestry from them.

Harry Lauder wrote "Keep Right On To The End Of The Road" as therapy

after his only son was killed on the Somme, but here he's represented by

"I Love a Lassie" recorded in 1905. I always think that he and Will

Fyffe are acquired tastes that fall between the genuine and the fake, but

there is no denying the fascination of Fyffe's "drunken" diatribe against

the rich half way through "I Belong to Glasgow". He delivers that

with real hatred behind the stage intoxication. Look at the date on the

recording. It's 1929, Wall Street is crashing, and the divide between rich

and poor which, as I have said, was always at the heart of the Music Hall

in the house and on the stage was never further apart. But by then the Golden

Age was over and the loss of the Empires was nigh.

This is an indispensable record for those who love the world of the old Music

Hall.

Tony Duggan

Comment received

I'll give you £100

if you can show me the words and music of

'a Marie Lloyd song called She Sits Among

The Cabbages and Peas or Leeks' It may be

a good story but it just aint true.

Max Tyler.

Historian and Archivist. British Music Hall

Society