Born in Northampton on 21st

October 1921, Malcolm Arnold studied composition

with Gordon Jacob and trumpet with Ernest

Hall at the Royal College of Music. In

1941 he joined the trumpet section of

the London Philharmonic Orchestra, becoming

principal by 1943. After two years of

war service and one season with the BBC

Symphony Orchestra he returned to the

LPO in 1946; but composition was already

becoming his priority and he had already

produced a catalogue of attractive works,

an early example being the comedy overture

Beckus the Dandipratt, Op.5 (1943), recorded

in 1948 by the LPO under their principal

conductor Eduard van Beinum. That same

year Arnold won the Mendelssohn Scholarship

which enabled him to spend a year in Italy;

on his return he decided to concentrate

entirely upon composition. His experience

as an orchestral player stood him in good

stead as a composer. He quickly built

up a reputation as a fluent and versatile

composer and a brilliant orchestrator,

many commissions were to come his way.

Arnold has written works in almost

every genre for amateur and professional

alike, including nine symphonies, five

ballets, two operas, 20 concertos, overtures

and orchestral dances, two string quartets

and other chamber music, choral music,

song cycles and works for wind and brass

band. Somehow, in the midst of this

prolific creativity, Arnold has found

time to score over 80 films including

the Academy Award-winning score for

Bridge on the River Kwai, written in

only ten days and Inn of the Sixth Happiness

which brought an Ivor Novello Award.

In 1969 Malcolm Arnold was made a

Bard of the Cornish Gorseth, he was

awarded the C.B.E. in 1970 and received

honorary doctorates from the universities

of Exeter (1969), Durham (1982) and

Leicester (1984). He was made a fellow

of the Royal College of Music in 1983

and is an Honorary R.A.M. In 1986 he

received the Ivor Novello Award for

outstanding services to British music.

He was Knighted in 1993.

Arnold's music springs directly from

roots in dance and song. Typically it

is lucid in texture, clear in draftsmanship.

His lighter entertainment pieces are

easy to listen to and rewarding to perform.

As an inventor of tunes, his powers

seem to be inexaustible, and he is prodigal

with his gifts; the 'big tune' in the

modest little Toy Symphony, for example,

is just as much a winner as the many

memorable themes in many concert works.

Many of these are firmly established

in the concert repertory. Yet for those

who have ears to hear, his works frequently

give more than a hint of a complex musical

personality and of dramatic tensions

not far below the surface. In fact there

is scope in Arnold's music which reflects

his profound concern with the human

predicament and also in his belief that

music is "a social act of communication

among people, a gesture of friendship,

the strongest there is."

A Short Introduction to the

Music of Sir Malcolm Arnold

by Vincent

Budd

This is a slightly expanded version

of an article written for a local newspaper published in the Outer

Hebrides. Amendments and additions have been made to the original

text, and a brief biographical sketch has also now here been included.

For those new to Arnold and wishing to find out more about the

composer and listen further to his music, a brief bibliography

and a short discographical note have also been appended. Those

who have already caught the Arnold bug, may be interested to know

that there is a Society devoted to his music:

https://www.malcolmarnoldsociety.co.uk/

|

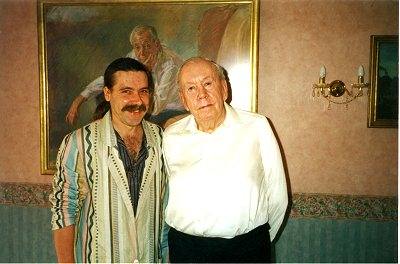

| Sir Malcolm Arnold at

his home in Attleborough, Suffolk

with the author in unfortunate

jacket disaster. The composer

has in recent years suffered from

periods of ill-health and has

stopped composing but is now looked

after by Anthony Day. |

I

Sir Malcolm Arnold rightly

now stands as one of Britain's most

pre-eminent and cherished musical figures.

Fellow composer William Alwyn, also

from Northampton, once described Arnold

as having walked into his life like

a 'genial tornado'. The simile is spot

on - as the man, so the music. Arnold's

works have their serious and cerebral

priorities and contain deeply moving

moments of elevating mindfulness and

heart-felt emotion, not least in his

major swansong, the 9th Symphony:

yet they are also filled with such teeming

tunefulness, such ebullient vitality,

and such a positiveness of spirit that

they constitute not simply an oeuvre

of uncandid charm, but one of the most

endearing contributions to the music

of these Isles this century. His scores

always possess, as becoming a brilliant

orchestral trumpeter, a masterly understanding

of orchestral effect. Warmly expressive

yet devoid of superfluity, they contain

a consummate sense of structure and

an acuity and conciseness of expression

that make an undeniably immediate impact:

they are intelligent and clever, sometimes

stunningly wrought and intricate, but

often full of humour, characteristically

open-hearted and unpretentious, occasionally

brilliantly anarchic and riotous. Indeed,

his music contains some of the brightest

all-conquering tunes any music lover

is likely to hear in one lifetime on

planet earth and his gift for attractive

and shapely melodic invention is seemingly

almost boundless.

Arnold has over the

years been the butt of some worthless

critical abuse and undergone periods

of unfashionableness, not least for

his contumacious eclecticism - a characteristic

invariably a bit scary for the more

insecure and blinkered critic who must

make verdict. The composer once wrote:

'One of the great curses of the present

day is our apparent need to be regimented,

and I would suggest that we could use

the freedom that the arts give for a

wide variety of expression in a wide

variety of styles, as an antidote to

our narrow lives'. Arnold's muse reveals

a humanitarian and democratic spirit

eager to transcend our sometimes all-too

myopic musical landscape and ready to

embrace rather than exclude the contrasting

and multi-faceted temperaments of the

human soul; and his compositions are

filled with an ever-flowing musical

invention that has a far-ranging emotional

appeal. Like any self-respecting free-spirit,

he retained a worthy respect for the

time-honoured forms and techniques of

orchestral expression: but he was unconcerned

with academic respectability and was

never afraid to flout convention, juxtaposing

diverse and contrasting musical modes

in his work; a radical spirit always

willing to look forward and beyond,

impassioned, unblinkered, and unhindered

to incorporate other musical cultures;

unashamedly happy to employ a whole

variety of idioms into a single piece

- jazz, folk, and popular music could

all be plundered with marvellous result.

An Arnold piece can jump from musical

profundity to extravagant trifling,

quiet sobriety to vibrant raciness,

deep seriousness to buffoonish self-mockery

in a bar - often to scintillating effect.

He was quite unafraid to use a cliché

when appropriate and he sometimes engagingly

wore his loves and influences (e.g.

Mahler, Berlioz, Sibelius, and Shostakovitch)

on his compositional short sleeves:

but his works were marked by a clear,

undeniable, and abiding individuality.

Sibelius once famously remarked in a

conversation with Mahler that what he

admired about the symphony was its severity

of form and the profound logic that

created an inner connection between

all the motifs. Mahler countered: 'No,

no. The symphony must be like the world

- it must contain everything'. Arnold

would have assented to both - for him

there was no stylistic dilemma to resolve.

II

Malcolm Henry Arnold

was born in 1921. A handsome set of

silver knives, forks, and spoons lay

ready on his plate. He was the youngest

of five children from a well-to-do Methodist

Northampton family involved in - you've

guessed it - the footwear business,

but also with a worthy lineage of involvement

in music especially on his mother's

side: his mother was herself a fine

pianist and obviously a dominant figure

in his life; his father also played

the piano and organ. Arnold was educated

privately and at home, and this included

tuition in violin, piano, violin, and

later, the trumpet, the instrument with

which he was to make his first real

mark on the musical world. He was by

his own admission thoroughly spoilt

as a child: unlike many an aspiring

musician or composer, he certainly appears

to have been given every encouragement

to pursue his obvious precocious musical

talents. He was soon too showing strong

streaks of rebelliousness and emotional

impulsiveness, volatile tendencies which

were to have both comic and more serious

consequences during his life - the words

'roller' and 'coaster' sometimes spring

to mind. (According to his friend, the

flautist Richard Adeney, he intended

to commit suicide at the age of thirty

as he did not want to become 'a boring

old man'.) As a young man he became

besotted with jazz and at the age of

twelve he saw Louis Armstrong play in

Bournemouth. This had a catalytic and

lasting effect, and by the age of fifteen

he was having trumpet lessons from Ernest

Hall. Hall was Professor at the Royal

College of Music and it was there that

Arnold entered in 1938 ostensibly to

pursue his musical education in real

earnest: composition and trumpet were

his principal subjects, though he also

took courses in piano and conducting.

In the end, having already gone AWOL

on at least one occasion, he never took

his final examinations and instead towards

the end of the second year of his course

joined the London Philharmonic Orchestra

as second trumpet (becoming principle

in 1943), an appointment that perhaps

proved to be more vital to his musical

education than his short stay at RCM.

In 1941 Arnold married

Sheila Nicholson, who gave birth to

two children, Katherine and Robert.

However, the war years were not the

happiest of times for the trumpeter

and then still part-time composer. He

was at first a conscientious objector,

but 1944 saw a change of heart. The

army predictably did little for his

emotional well-being and it proved a

frustrating and regretful experience,

and after accidentally-on-purpose shooting

himself in the foot (potentially a very

serious offence) he was discharged on

medical grounds. There was then a brief

stint with the BBC Symphony Orchestra,

until he returned to the LPO where he

stayed until 1948. He had of course

been writing all this time and a number

of scores had been played in the concert

hall: but it was a score from 1943,

the overture Beckus the Dandipratt,

which saw the first real recognition

of his talents as a composer. In 1948,

he was awarded the Mendelsshon Scholarship

by the RCM, and following a period in

Italy, he returned to Blighty to take

up composing as a full time profession.

Symphony No.1 was completed the

following year, and he was soon at work

on a second. In 1947 Arnold had also

written his first film music: it of

course provided an important source

of well-needed income, but it also proved

an important outlet for his prodigious

muse and masterly skills, with his soundtracks

for David Lean being of particular note;

and it was not until 1969, with nearly

120 scores to his name, that he decided

to discontinue this line work. Given

all his other activities during this

period, it is a wonder where Arnold

found all the time and energy.

Over the next decades

Arnold produced some of the finest music

of any British composer working during

this period, even though his critical

standing with the nation's critics (compared

say to Britten and Tippett) failed to

match it much of the time, especially

in the '70s. His life has been rich

in friendships and he has written concertos

and instrumental music for, inter

alia, Richard Adeney, Larry Adler,

Julian Bream, Dennis Brain, James Galway,

Benny Goodman, Leon Goossens, Yehudi

Menuhin, and Julian Lloyd Webber. Overtures

such as Tam O'Shanter, The

Smoke, Curtain Up, the Sussex,

Festival, and Grand, Grand,

and the ballets Homage to the Queen,

Rinalda and Armida, Sweeney

Todd, Electra, and Ierusalemme

Liberatat all helped to add to his

reputation. A wondrous and engaging

set of chamber and instrumental music

too figured large in his output. All

this was set alongside numerous other

'incidental' works (sinfoniettas, suites,

music for children, piano, brass, and

vocal pieces, small-scale operas, etc.).

However, it was in the symphonies that

Arnold reserved some of his more serious

and most substantial musical statements;

yet they always remain to the point,

unstuffy, still often marked by his

abidingly incandescent voice even at

their most serious. By 1978 he had completed

eight symphonies, but there was to also

to be a ninth, a deep-felt and intense

musical statement, completed nine years

later in Norfolk.

Indeed, the history

of Arnold's life and music has been

marked by a distinctive cultual geography

which has often made a particular import

into the form and character of his work.

During the sixties, following the failure

of his first partnership, he married

Isobel Gray and the couple left London

to live in Cornwall, where he soon began

to make a more than telling contribution

to the musical life of the West Country.

It was here that Isobel gave birth to

the third of Arnold's children, Edward,

who, after much trauma, was eventually

diagnosed autistic. Then in 1972 he

moved to Ireland, and Isobel and Edward

joined him soon after. Sadly, his personal

life began to deteriorate and there

was an attempt at suicide: this was

followed by divorce, enforced estrangement

from his young son, and a return to

the mainland, and an almost complete

breakdown. Arnold's life had always

been full, replete with extremes of

both high emotion and social honour

and depressions and personal tragedy,

but the end of the seventies and early

eighties saw Arnold at possibly the

lowest ebb of his life. Although at

first he still managed to produce work

of outstanding quality, including the

8th Symphony and the Philharmonic

Concerto, it did lead to a period

of compositional silence. Not only was

he eventually left in a very precarious

position pecuniarily, but he also became

very ill, and indeed close to premature

death; a situation obviously not helped

by his propensity and capacity for alcohol

which had always been an important part

of his adult life. Nor was it to be

aided by the seemingly uncaring attitude

of his new-found 'guardians' back in

his home town of Northampton. It is

a tragic episode in Arnold's life from

which, though much improved, he has

never fully recovered: but it was to

have a happy ending. 1984 saw the arrival

of Anthony Day into Arnold's existence,

and it was he who literally saved his

life and provided a passage-way out

of his personal 'hell'. The pair moved

to Norfolk, Day's home county but also,

coincidentally, an area important in

Arnold's family history. Anthony has

been his constant carer and 'personal

assistant' ever since and has not only

helped restore the composer's health

and rectified his financial situation,

but also been active in the promotion

of Arnold's music. Just as importantly

he encouraged Arnold to begin composing

once more, and not surprisingly it is

him to whom Arnold's 9th and final symphony

is gratefully dedicated. Arnold began

work on his Op. 128 on 12th August 1986,

Anthony Day's birthday, and it was apparently

completed just eighteen days later.

Sir Malcolm Arnold has now ceased to

compose, but he does not, he says, miss

it.

III

If you think you have

never heard any of Arnold's music, you

are probably mistaken. TV viewers are

probably familiar with the theme to

What the Paper's Say (from his

English Dances), most men

at least have enjoyed a St. Trinian's

film at one time or other, and Bridge

on River Kwai is undoubtedly a screen

classic. Arnold wrote the music for

all three. In recent years, after a

period of comparative neglect, the appreciation

of the composer's music has undergone

something of a renaissance, and though

a good amount of material (especially

his film music and small-scale operas)

remains to be recorded, he is at present

quite well served in the catalogue.

Space here permits the selection of

just three

CD releases which perhaps give a

particular and special insight into

the compositional life of this outstanding

musical spirit and provide worthy points

at which to begin an exploration of

his life's work: few music lovers could

not be captivated by the sheer magical

brilliance of this marvel of British

music.

Return to: